What does it mean to be mad? Insane? Crazy?

Do these things exist outside the realms of reason?

If they’re unreasonable how can they be understood by reasonable means?

And what if, long ago, the mad led better lives than they did now? What would it mean for our society if fools were once closer to kings?

We think of science and medicine, including psychiatry, as improving gradually over time.

But is this really the case? Or, as societies and cultures shift and change, do we just create a different kind of madness?

How do we draw these lines?

Take one of those lines. The line that was drawn around leprosy in the middle ages, a contagious disease with visible marks that might invoke fear or the hand of god.

For a long time, leprosy was one of the most feared diseases in Europe.

In the high Middle Ages there were some 19,000 leper houses across the continent. England had a population of just 1.5 million but had 220 leper houses.

Lepers lived in colonies – some with their own currency – segregated from society.

But by the 14th century, all across Europe, they were beginning to empty. And by 1627 Saint Bartholomew, what was once the biggest in England, had closed altogether.

We’re not certain why leprosy disappeared but it was likely the result of segregation and the end of the Crusades – quick migrations between Europe and the Middle East.

Now, the Leper colonies stood empty, a lasting symbol of exclusion and fear.

Some years later, during the Renaissance, strange ships wound their way along the canals and rivers of Europe. They existed maybe only as an idea in literature – a ships of fools, transporting the mad away from the cities where they might find their sanity.

While it’s unlikely these ships existed, madness during the Renaissance was often dealt with by expulsion. Towns banished the mad from inside their walls, leaving them to run wild or entrusting river boatmen to escort them away.

But to Renaissance Europe the mad held a special place, potentially considered unique sources of wisdom. Madness was the underside of man, it magnified frailties, dreams, illusions, an imagination gone wild, but it was still a kind of truth.

If madness was the sign of god’s hand then there must be good reasons.

The Renaissance also led to new interpretations of madness – as old knowledge from the ancients was rediscovered there was a growth of meanings to madness, a web of connections that became more complex.

Foucault wrote that, ‘Screech owls with toad-like bodies mingle with the naked bodies of the damned in Thierry Bouts’ Hell, the work of Stefan Lochner pullulates with winged insects, cat-headed butterflies and sphinxes with mayfly wingcases, and birds with handed wings that instil panic. While it fascinates mankind with its disorder, its fury and its plethora of monstrous impossibilities, it also serves to reveal the dark rage and sterile folly that lurks in the heart of mankind’.

If madness is linked in literature and art to the devil or to the end of the world or to hubris, emotion or pride then it contains divine wisdom.

Then the age of reason began. The discovery of science, of rationalism, and careful study. Ironically, this didn’t lead to the study of madness but a fear of it. The age of reason was to reduce madness to silence.

When Descartes – the father of rationalism, of reason, of the Enlightenment – considers in his famous Meditations whether he might be mad instead of reasonable he outright rejects the idea.

During the age of reason, if men are reasonable then madness must be banished. Madness became a problem.

In the seventeenth century, madness was placed into a zone of exclusion, a threat in theory and philosophy that the period didn’t know what do with.

‘It is well known,’ writes Foucault, ‘that the seventeenth century created vast houses of confinement, but it is less well known that in the city of Paris, one out of every hundred inhabitants found themselves locked up there within a matter of months’.

In 1656 (six years after Descartes died) the Hospital General was opened in Paris.

Further houses were opened for invalids ‘of both sexes, whatever their age or place of origin, regardless of their quality or birth, and in whatever state they present themselves, able or disabled, sick or convalescent, curable or incurable’.

‘The Hôpital Général was a strange power that the king set up half-way between police and justice, at the limits of legality, and forming a third order of repression’.

These general hospitals spread across France.

They were ‘curious’ institutions, somewhere between assistance and imprisonment, often built in or on the sites of the leprosy communities. Foucault writes that, ‘Together with a desire to assist was a need to repress, a duty of charity and a will to punish’.

The authorities declared that, ‘To that end the directors will have the following at their disposal: gallows, iron collars, prisons and dungeons inside the Hôpital Général and dependent buildings, which they may use as they see fit’.

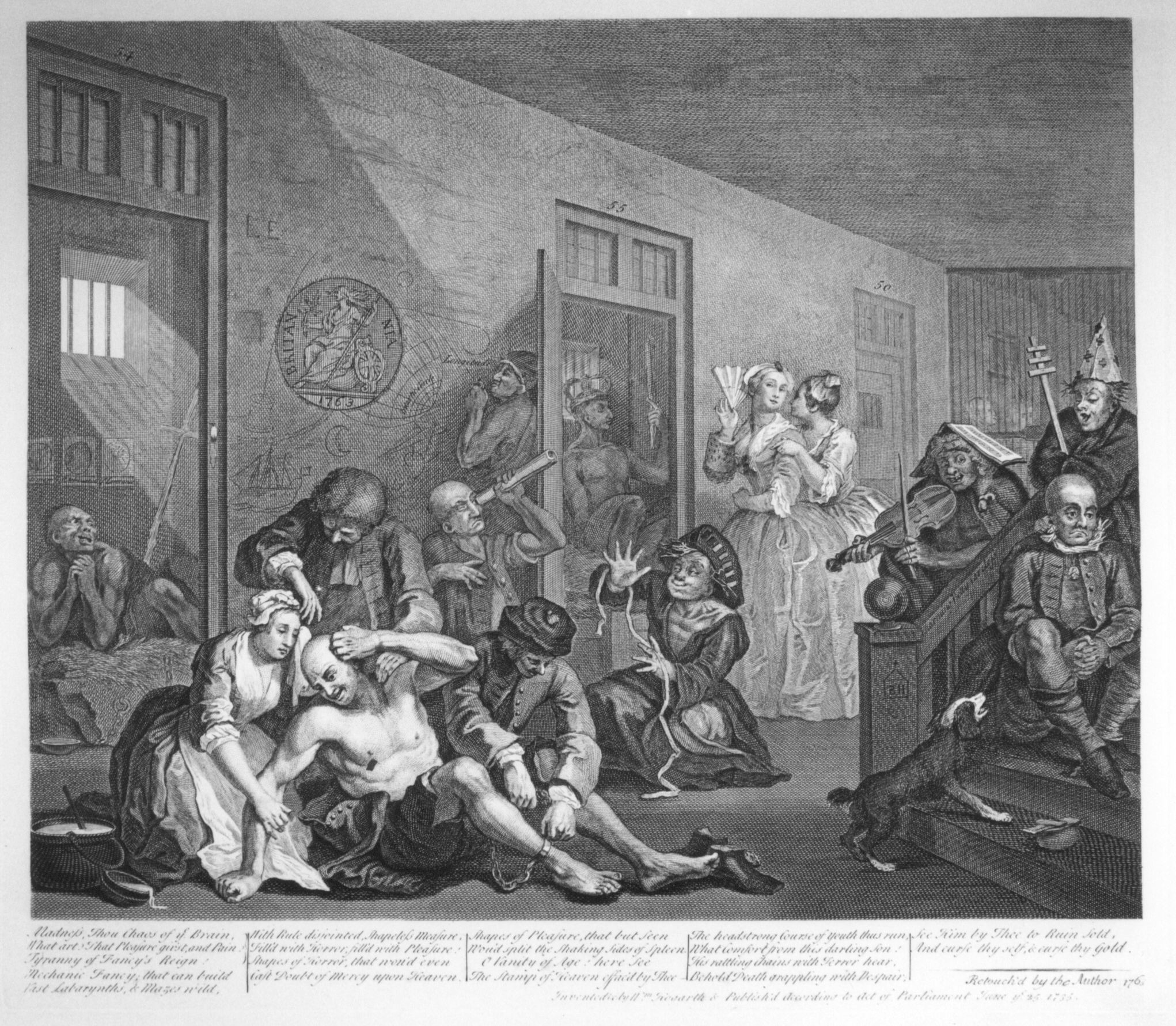

Madhouses were not medical but ‘semi-judicial’ institutions of segregation where the poor, sick, idle, and mad were separated from healthy, reasonable, and rational society.

‘Confinement,’ writes Foucault, ‘the signs of which are to be found massively across Europe throughout the seventeenth century, was a ‘police’ matter’.

Who was designated for isolation, for segregation from reasonable society, was a product of how reason itself was interpreted. Where that line was drawn and why it was drawn in the way it was, was directly related to the moral, social, and religious beliefs of the day.

In other words, reason had to contain a trace of madness.

At the turn of the eighteenth century, just as the madhouses were being opened, workhouses appeared across England. In 1607 a pamphlet circulated in France that argued that a hospital for the poor should be founded so that the unfortunate might find ‘life, clothes, a trade and punishment’.

Punishment. Because poverty was deserved. It was the sign of wrongdoing in the eyes of many religious. The devil’s poor. Work and labour were the way back to god and health.

The devil’s poor were, ‘Enemies of good order, lazy, deceitful, lascivious and given over to drink, they speak no language other than that of the devil their father, and curse the Bureau’s teachers and directors’.

In 1532, Paris authorities rounded up beggars and forced them to work in the sewers.

‘it is expressly forbidden’, it was announced in Paris, ‘to all persons, regardless of age, sex, birth, social standing or place of birth, their capacity or inability to work, sick or convalescent, curable or mortally ill, to beg in the city and outskirts of Paris, or in the churches, at the doors of churches, at the doors of houses or in the streets, or anywhere else, publicly or in private, by day or by night’.

‘All the poor who are able should do a day’s work, both to keep them from the idleness that is the root of all evil and to get them used to working, while enabling them also to earn a portion of their food’.

These institutions weren’t correctional, medical, or humanitarian, but moral institutions. That is, they were defined and organised by the moral and ethical attitudes – religious or otherwise – of the time and place.

They were ‘granted full powers where authority, direction, administration, commerce, policing, tribunals, correction and punishment are concerned’.

If only the social, moral, and religious norms of society were followed, the poor, idle, infirm and mad might find their reason again.

Nicolas de La Mere, in A Treatise on the Police, declared that, ‘If men were sufficiently wise to comply perfectly with its requirements, it would be the sole matter that the police should treat. Then there would be no more corrupted morals, temperance would ward off sickness, hard work, frugality and prudence would ensure that man never wanted for anything, charity would banish vice, and public order would be assured’.

If reason determined what was unreasonable what reasons were there for dealing with insanity in a specific way? During the age of Enlightenment, when the mad were confined, it was primarily justified for the reason of avoiding public scandal.

Scandal, and therefore, disorder, was a special type of evil and so must be avoided at all costs. Social disorder, of course, is the opposite of an ordered society, and so scandal, along with idleness and poverty should be locked away.

The insane were also likened to animals.

It was rationality, as Aristotle had argued, that made man something more than animal. The lower beasts had passions, fears, desires, but not reason.

But animality could still be traced in ‘civilised’ man. It sometimes got the better of people.

This is the righteous divide between the passionate, emotional, ancient and unreasonable animal side of man – the dark underbelly – and the logical, rational, reasonable and enlightened side, the modern, the civilised.

Madness was born from animality. Writers noted how madmen and women could lie on beds of straw without covering.

Phillipe Pinel, the French physician, admired the ‘constancy and the ease with which certain of the insane of both sexes bear the most rigorous and prolonged cold’.

But, contradictorily, there was logic to the animality. One farmer in Scotland claimed he’d found a cure to insanity.

Pinel writes that, ‘his method consisted in forcing the insane to perform the most difficult tasks of farming, in using them as beasts of burden, as servants, in reducing them to an ultimate obedience with a barrage of blows at the least act of revolt’.

In pure animality madness was to find its truth and its cure since madness becomes reason and humanity becomes unreason. ‘Unchained animality could be mastered only by discipling and brutalizing’.

Foucault writes that, ‘Madness threatened modern man only with that return to the bleak world of beast and things, to their unfettered freedom’.

It is in the logic of animality that madness finds its commensurability with unbridled and untamed passion, insanity links to emotion, drives, and ultimately, morality.

A disequilibrium of the passions and emotions could lead to madness. City life, for example, in its unnatural rhythms and ‘multiplicity of excitations’, could drive men insane.

But how that disbalance was conceptualised determined not just who was considered mad, but how, Foucault argues, madness itself was experienced.

And again, rather than being outside of reason it had a logic to it. ‘the ultimate language of madness is that of reason’.

One man suffers from melancholia – a depression and a fixation on a single idea, an obsession.

He believed that a demon was haunting him from the crime of killing his own son.

On investigation the doctor found that the man had taken his son to the beach where he had drowned. As a father he was responsible. And homicide is punishable by god.

There is a logic, a belief that becomes so powerful that it manifests its truth in all experience – ‘a delirious discourse’, Foucault writes.

If I imagine that I am made of glass I am not mad, but if I reason from this that I am fragile, in danger of breaking, that I must not be touched, that all my words are transparent, then this way madness lies.

The diagnosis of unreason and the experience of madness is found through reasonable means.

Take hysteria.

‘It attacked women more often because they had more delicate constitutions, not used to hard labour and are more inclined to luxury and softness. Those with too much sympathy for others or the world develop a softness in the nerves’.

It is here that morality is introduced into the unity of interpretation. The elements of the interpretation form a complete and universal theory.

‘Women who have “frail fibres”, who are easily carried away, in their idleness, by the lively movements of their imagination, are more often attacked by nervous disease than men who are “more robust, drier, hardened by work.”’

Treatments also operated in this unity of logic, meaning and interpretation. Iron cures because it’s strong. Bitterness, having the qualities of sea water and because sea water corrodes, cleans and purifies. Soap because it eliminates.

But it was what you did, saw, how you acted and lived your life, that mattered.

This had a damning result: all of life and illness could be judged by moral questions. Things that were not natural, which novels were read and plays were watched, what passions desired forbidden things. In all of this a deeper guilt – a moral fault – could be found.

Remember that 1 in 100 people were locked up in Paris. The idle, the poor, the infirm, and the mad were placed, in abstract and in practice, in a box, a question mark. But in the middle of the 18th century a fear began to spread. A fear of sickness, of prison fevers, an ulcer on the body politic, an evil blot on the landscape, a rottenness. The cities were at threat of contagion. In 1780 an epidemic spread through Paris and rumours said that it started in the General Hospital.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century this fear led to a concern across Europe. Too many were locked up. There must be other ways.

Was this a humanitarian advance? It had typically been interpreted this way. But Foucault argues it was more political, more social, more cultural than simply an advance in philanthropic awareness.

So many were condemned that ministers, police officers and magistrates received endless complaints that ‘decent’ men were being forced into confinement. The elite’s own.

At the same time people who could labour, who could work and contribute, were being forced into chains. Mirabeau asked, ‘why are these people not employed at those tasks which might prove harmful to voluntary workers?’

At this time an economic interpretation of poverty was beginning to supplant a religious interpretation. Where once the pauper was condemned and had no place, now one could be found for him.

It is in this context that the firm asylums opened their doors.

‘This house is situated a mile from York, in the midst of a fertile and smiling countryside; it is not at all the idea of a prison that is suggests, but rather that of a large farm; it is surrounded by a great, walled garden. No bars, no grilles on the windows’.

The retreat was run by a Quaker, William Tuke.

But beneath the myths of humanitarian intervention, of philanthropy and liberation, there was an ‘operation’ of organisation that continued to aim to entrap madness by moral reason.

Tuke placed responsibility on the patient’s shoulders, on their own consciences. Instead of simply being locked up they must become aware of their own guilt, conscious of themselves as free and responsible subjects, reasonable subjects.

For Quakers, work was the first moral treatment. Patients were observed and judged; authority replaced repression.

Madness was confined ‘in a system of rewards and punishments, and included in it the movement of a moral consciousness’. ‘Everything was organised so that the madman would recognise himself in a world of judgement that enveloped him on all sides; he must know that he is watched, judged, and condemned’.

This wasn’t unreason liberated but madness mastered. Moral uniformity was expected. ‘The asylum sets itself the task of the homogenous rule of morality, its rigorous extension to all those who tend to escape from it’.

This is where reason and unreason meet most acutely. The doctors were not medical doctors, not scientists, but ‘wise’ moral doctors; arbiters of the rules of society.

Everyone who has worked on the history of psychiatry since has worked in Foucault’s shadow. He revolutionised the field.

He looked at history not as a history of administration, of records or politics, or what the psychiatrists said happened, but as a question of how something was experienced, and how what we think of as timeless actually changes over time.

Foucault introduced difficult and exciting questions in both history and philosophy. Where might the voice of the excluded and silenced be heard? To what extent is madness a product of society’s attitudes towards it?

‘how,’ he writes, ‘can a distinction be made between a wise act carried out by a madman, and a senseless act of folly carried out by a man usually in full possession of his wits?’ ‘Wisdom and folly are surprisingly close. It’s but a half turn from the one to the other’.

What does it mean to transgress? And how is it possible to reach something out of reach, something beyond reason?

‘We could write a history of limits’, Foucault writes, ‘of those obscure gestures, necessarily forgotten as soon as they are accomplished, through which a culture rejects something which for it will be the Exterior’.

And that’s what he’s looking at – the limits, the dark edges of reason, which of course says a lot about how we define reason too.

But Foucault has been criticised by historians and philosophers. Did the ship of fools really exist? Were the mad really excluded from any idea of reason? These are questions I’ll return to next time.