This is my box of human nature. It contains everything that’s in your nature. What does that mean? In short, if it’s in your nature, it’s unchangeable, undeniable, part of your very constitution, and in a box because it is impervious to everything outside of it, locked in a cage, unadaptable. The question is: what do you think is in the box? Do you think the box is full? Or empty? Somewhere in between?

On the other hand, outside of the box, we have the environment – all that stuff around you, that’s ever been around you, that has an effect on you, how you’re formed, how you developed, who you are.

Does any of this get inside the box? Maybe the box is empty – a blank slate, as the philosopher John Locke put it – filled up as you grow up, as you develop.

Seriously, what do you think might be in here? We’re going to skim over some complicated sounding things: DNA, genetics, epigenetics, methylation, phenotypes, stress, twin studies, Steven Pinker, and early intervention programmes. But I want to avoid being technical, as much as possible, because most fundamentally, most simply, this box is about a fundamentally philosophical idea: freedom.

The nature-nurture debates inform almost every area of human life – from biology and botany to economics, literature, and history.

To simplify, thinkers on the nature side have, in varying ways, argued that at least parts of your body and mind are behind an impenetrable skin, cannot be gotten to by upbringing, education, politics, or culture.

They’re often referred to as nativists. They believe we have an innate nature. Of course, it is undeniable that people grow, change, adapt, interact with the world, but nativists believe that this change, again in at least some part, emerges from the box. Imagine a one-way street. For example, you have an innate eye colour or a creativity that comes out of your DNA – nothing gets to it, it is just in you.

To take one example, the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes argued that we are naturally competitive, we seek glory, and are prone to violence. These things came out of us – and had an effect on others – but no culture, politics, education, upbringing could change that fundamental, universal and timeless fact.

On the other hand we have empiricists. They believe in a two way street instead of a one way street.

Another English philosopher, John Locke, for example, thought the human mind was a tabula rosa, a blank slate – and all humans were shaped, in different ways, by their experiences – what they see, hear, touch, are taught, how they’re raised. Experience comes in.

But let’s return to the nativists – the ones who believe we have a nature. What is it they actually believe is behind the barrier, in the box? Well, depending on who you ask, it can be anything from IQ, a capacity for violence, to economic self-interestedness, a propensity for addiction, a likelihood of a certain disease at a certain age, and the list goes on.

There are two things I want to think about here. First, what does the evidence say? And second, what are the consequences for philosophy and politics?

If nature is true, what does this mean? If nurture is true, what’s the best way of acting on it?

The central point that’s been made across the history of this debate is this: if people have a nature, trapped in the box, then it’s no good intervening to try and improve it.

Intervening here is the keyword: what parts of us a malleable? And what or who is shaping those parts? Who or what is intervening – nurturing – upon our lives? We’ll return to this at the end.

But first, the idea that we have a nature has been approached in countless ways – philosophically, psychologically, theologically – but the most persuasive, through the 19th and 20th centuries, the best place to start, is biology: the study of DNA and our genes.

Okay, bear with me while we get technical for a second – to get to the foundation of nature/nurture we have to talk about DNA.

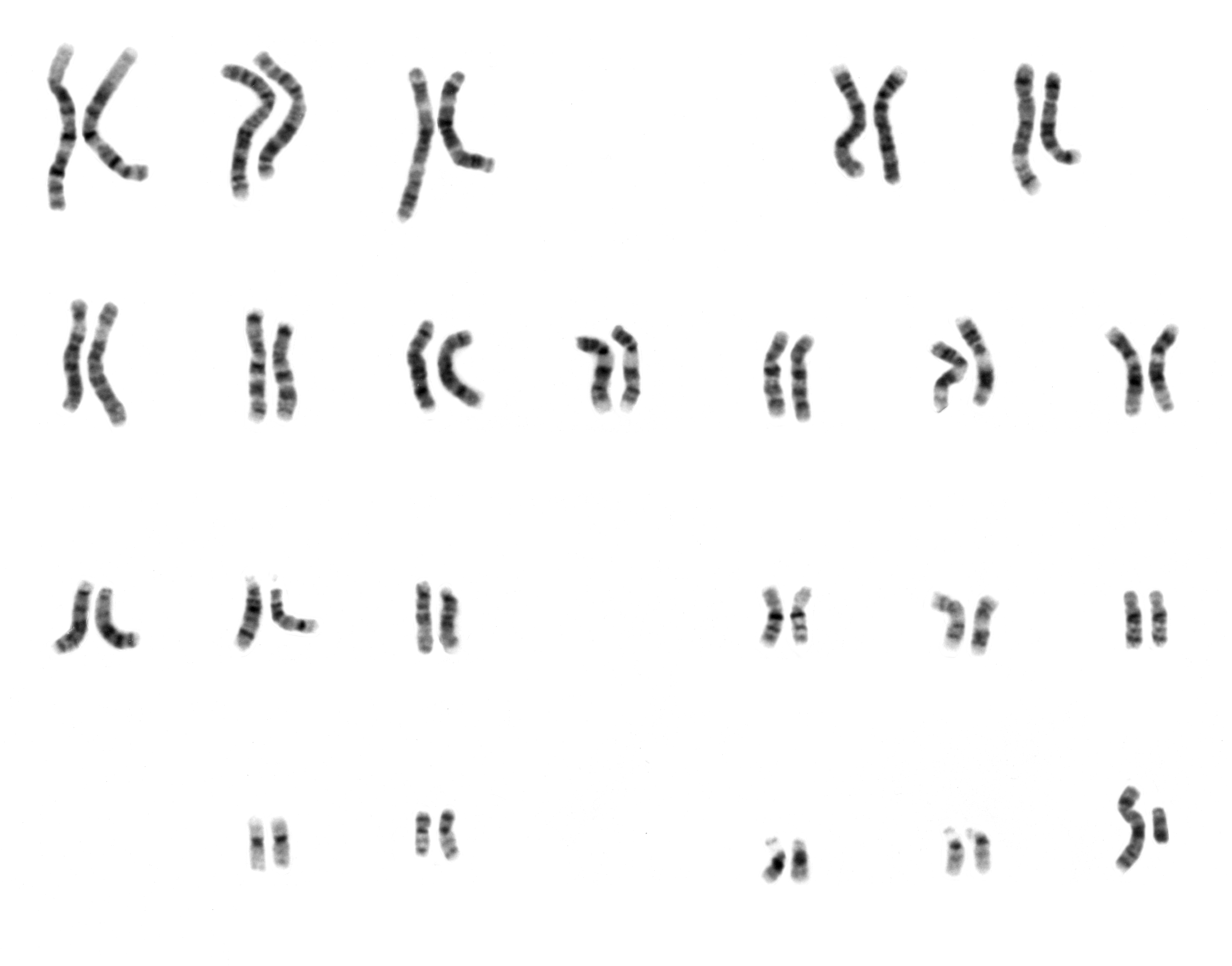

All of life is about replication. You came – as most species did – from a single cell, a cell that contains everything that is in your nature, in the box. That cell duplicates and divides into 2, which divide into 4 to 8 to 16 to 32 and so on, until, in a human, they reach 50 trillion.

Each of those cells contains DNA in the nucleus – which is made up of a long double helix of chemicals called base pairs. Humans have 3 billion base pairs and they are 99% identical for everyone. The order of those base pairs – which are made up of only four molecules, AGTC – determine everything from eye colour to how to make a liver function. They tell the cell what to do and how to replicate itself. When a cell replicates, the DNA helix unravels and tells the cells which ingredients it needs to make two new strands.

DNA and the genes they make up guide everything. They tell the cell which proteins to make, which are the building blocks of all life – proteins make up the structure of the body, are used to transport blood, used as antibodies, come in different shapes and sizes – there could be up to 400,000 proteins in the human body, and the code for how to make them comes from the DNA strands in each and every cell.

Okay, so if anything is in the nature box, DNA is. It’s at the bottom of that one-way street – the absolute inside. DNA replicates itself, and passes itself on, into the next box it creates.

It contains the ingredients, the blueprint, the code – to make someone tall, or intelligent, or a self-interested Hobbesian brawler, or autistic, or quick-witted – and no amount of environmental stuff outside can change it because it stays the same – in every cell – from when you were born to when you pass your genes to the next generation.

But is this really true?

Remember, all of life is the duplication of cells and all cells contain the same DNA – your human nature – and your DNA is your DNA – unchangeable by the environment around it.

But when this was discovered in the 19th century, people began to wonder, if DNA makes everything but is always the same, how does it know when to make a head, a nose, a liver, a neuron, a hair, a nail, a blood cell?

When that first cell you came from divides in two, does one contain the bottom half of the body and the other the top?

One scientist – Hans Driesch – even decided to separate the divided cells of sea urchin embryos thinking they’d grow into two separate deformed sea urchins – a top and bottom – but, to his surprise, they grew into two normal, healthy urchins.

In other words, when our cells divide, there must be some mechanism for telling the cells how to divide. Something to tell the DNA what to do. So it cannot be a one-way street – something, some message has to go the other way, has to get to the box to signal to it what to do.

Where does this come from? The answer, of course, is their environment. DNA must be nurtured in some way.

Nobel laureate Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard writes that the cell, ‘receives signals and information from the environment, including the neighbouring cells. This information is transmitted to the genes… In this manner, the fate of a cell is dependent on both the cytoplasm and external influences’.

So what the DNA does depends on how it interacts with other molecules, proteins, and cells it encounters, everything around it. It receives signals from the environment.

But how?

Only in the last few decades has a revolutionary answer to this question been discovered – one that is having a huge impact on almost every field from biology to philosophy: epigenetics.

Okay, back to that one-way street. Genetic determinism is the idea that your characteristics and traits come out of the box – that they are nature – and they come out in the same way regardless of any environmental interaction with them. They come out of the DNA and make you.

Epigenetics – meaning ‘on’ or ‘above’ genetics – is the discovery that whatever’s in the box can be switched on and off, and even more than that, can act like a dimmer switch, producing more or less.

To know what to do, DNA needs signals from the environment. It needs to know which of the millions of combinations to execute and express. It simply cannot be unresponsive to environmental signals.

DNA contains so much data it boggles the mind. If unwound it would be two meters long. But certain molecules from the environment – called histones and methyl groups – can wind themselves around the DNA, bunch it up, so that particular parts of the DNA cannot express themselves – the information is silenced. This is called methylation. Another group of chemicals – acetyls – open the DNA up to be able to express itself again.

These processes are the ones that are right at the foundation of nature-nurture and show us that the duality is nonsensical. What we have is nature and nurture interacting, in a dance.

DNA has what biologists call regulatory sites that different molecules are able to bind to, changing the function of the DNA.

This discovery has had ground-breaking implications for so many areas – memory, cancer, depression, obesity, autism, addiction, ageing, exercise, nutrition, toxins. We’ll look at a few of these and then return to some philosophy to think about the implications.

Randy Jirtle and Michael Skinner write that, ‘The word “environment” means vastly different things to different people. For sociologists and psychologists, it conjures up visions of social group interactions, family dynamics and maternal nurturing. Nutritionists might envision food pyramids and dietary supplements, whereas toxicologists think of water, soil and air pollutants . . . [but scientists now have] evidence that these vastly different environments are all able to alter gene expression and change phenotype, in part by impinging on and modifying the epigenome’.

I want to ask this – where are the clearest places this process happens? Where does the environment affect us in ways we have direct evidence for? Are those places limiting or expanding our freedom? And how can we think more simply and philosophically about the consequences?

One, toxins and pollutants, have been shown to have an effect on the cognitive functioning of children. As do mercury and some plastics and pesticides. Pollution in the form of fossil fuel combustion has been shown to be associated with poorer test performance in kids. Frequencies of refuse collection, access to toilets, and cleanliness of water have all been shown to be associated with cognitive performance levels in many low income countries.

Of course, these all disproportionately affect poorer neighbourhoods.

Two, noise – aircraft, traffic, crowded living conditions – can all lead to poorer reading skills, higher blood pressure and an increase in stress hormones. Poorer parents have less time to stimulate infants, which has negative outcomes. A lack of stimulating materials – books, toys, etc – the same. Smaller classrooms have a positive effect.

Three: nutrition. It’s been found that a whole range of dietary habits leave epigenetic marks. Stress or famine – even when you’re in the womb – lead to outcomes like obesity and stress for decades into the future.

Four, five, six: stress, anxiety, and depression. Or mental health disorders more broadly.

Epigenetic studies have shown that rats who are licked and groomed by their mothers in the first 10 days of their lives respond better to stressful events later in life. Rats from low licking and grooming mothers are more likely to become startled and act fearfully throughout their lives.

Researchers found that their DNA had been methylated to stop a stress reducing hormone being produced.

Moore writes that the conclusion ‘is supported by a study of rat pups whose mothers were so stressed out that they treated their newborns abusively, by frequently stepping on them, dropping them, dragging them, or handling them roughly. As a result of this maltreatment, the offspring grew up to have altered patterns of methylation in their brains’.

Studies on mice and monkeys show similar epigenetic changes.

The breadth of these studies has important philosophical and political consequences. When it comes to stress, our brains are almost identical to rats, and furthermore, suicide victims have also been found to have high levels of genetic methylation, as have victims of abuse, and people whose mothers had depression while they were pregnant.

The thing with methylation is that it is hard to get off. It’s sticky. So early childhood experiences can literally get under your skin and really effect how your DNA operates for the rest of your life. Another study found a relationship between poverty in the first five years of life and epigenetic changes 20-35 years later.

It makes complete sense that animals and humans who experience more stressful early infant environments display high stress responses later in life, because their environment is a predictor of what your life might be like. You want your body to fight or flight more in areas with more predators or more loan-sharks. Poverty becomes biology.

But you might be saying of course there are things in the box. You couldn’t epigenetically adapt your DNA to produce wings and some people are surely naturally better at certain things and not as good at others. The DNA is still the DNA.

To think about this, we need to look at twins.

Identical twins have come from the same box. If they’re raised in different environments and the same stuff comes out – well, the box is unchanged. We’ve found nature.

The largest study of twins started in 1994 and looked at over 10,000 pairs of twins from the UK, the US, and the Netherlands.

It looked at twins who have been raised together, raised together up to a certain age, and raised apart, and looked for similarities and differences. If they’ve been raised apart all their lives but display identical traits then it must be in the DNA, regardless of how the DNA expresses itself.

To summarise briefly, researchers have estimated that around 50% of these twins traits could be attributed to their genes and 50% to their environment. So half and half.

It has been found in another recent study that young identical twins have similar epigenetic markings, but as they get older they diverge. In other words, as their environment and experience changed them.

Intelligence has also been found to be increasingly heritable as twins get older. That is, twins catch up with each other regardless of their environment. Some researchers have put the number as high as two-thirds nature and a third nurture.

But are we really seeing nature in these studies?

First, in one recent meta-study – that’s a study of studies – it was found that in most of them the term ‘raised apart’ was used very loosely. Many of the twins were actually raised together and many knew each other.

One studied reviewed 121 cases that claimed to be ‘raised apart’. Only three had actually been separated shortly after birth and only just been reunited. Most had actually had an average of 10 years together. Many of them were separated between 8 and 11. And most – almost all – shared the same culture, the same socioeconomic background, or knew each other as adults. On top of this, of course, they shared the same environmental signals in the womb and the same conditions in the first weeks of their lives.

It’s impossible to overstate the limitations of this. How many chemicals from the biological mother, the mother’s experiences, the surrounding culture is having an effect on genes is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to tell.

Look at this quote from epidemiologist David Barker about plasticity in development: ‘There are good reasons why it may be advantageous, in evolutionary terms, for the body to remain plastic during development. It enables the production of phenotypes that are better matched to their environment than would be possible if the same phenotype was produced in all environments . . . Plasticity during intra-uterine life enables animals, and humans, to receive a “weather forecast” from their mothers that prepares them for the type of world in which they will have to live. If the mother is poorly nourished she signals to her unborn baby that the environment it is about to enter is likely to be harsh. The baby responds to these signals by adaptations, such as reduced body size and altered metabolism, which help it to survive a shortage of food after birth. In this way plasticity gives a species the ability to make short-term adaptations, within one generation’.

Do separated twins really escape this environmental effect?

Okay, let’s try and bring this together. There are things in the box – propensities – maybe, but they are expressed in a wide variety of ways epigenetically, depending on their environment.

The way our nature is expressed is dependent on a wide range of phenomena – toxins, pollutants, stress levels, education, culture, politics, prolonged experience, levels of threat, in-womb development – the list is endless.

So are we more blank slates or do those propensities mean we have a type of human nature?

How can we make sense of this? There are things in the box – nature – but they get expressed depending on their environment – nurture.

Steven Pinker’s influential book, The Blank Slate, has a handy list of what he and anthropologist Donald Brown describe as human universals – meaning in our nature, impervious to the environment. Some of them – like tools, fear, fire, and cultural relativity, just to name a few – are almost risible, and at the very least simplified or shallow.

Fire – for example – is not human nature. It’s not in our DNA. It is environmental. I could conceivably live my entire life without it and we have innovations that supersede it.

But take fear. Ok, we all – I’d think, with a few exceptions – have experienced fear. Is it nature or nurture, then?

I’d say we have something like the raw ingredients or the ‘propensity’ for fear in the box. But the way those ingredients come together and are expressed is impossible to understand without interaction with the outside world.

I think you can still – despite things like a propensity for fear being in the box – make a strong case for something like ‘blank slatism’.

There is no sense in which an idea or feeling of ‘fear’ is imprinted on the mind, or body for that matter, in a universal, genetically-determined, and specific way before you are born. You have the biochemical propensity – the ingredients – for it in your DNA. The DNA is then epigenetically expressed in a variety of ways and depending on your environment (which includes the womb and the parents’ environment, remember), before it even gets to the blank slate of the mind. It’s then mixed with other cultural, social, and environmental factors that we absorb from experience and that code or script the biology, chemistry, and idea of fear in many ways which may or may not be expressed at certain times in certain ways.

Of course, what many of us are interested in when we’re talking about nature/nurture is not that we have fears, hormones, legs, fears, need food, have a culture – those ‘human universals’ – but how those universals are expressed by the environment, how our DNA unfolds, collides, and synthesises with the rest of the world. And that ‘genetic determinism’ – the idea that nothing gets to the box and everything comes out – justifies one political, cultural, and social position in particular – individualistic non-intervention. That because people are what their genetic inheritance is, intervention is an intrusive waste of time, money and resources.

So, if our genes are now conclusively affected by the environment, what does this mean philosophically, culturally, politically?

We are intervened upon by our environment, in a way that’s outside of our control. The obvious question is where does this happen in a detrimental way and where does it happen in a useful way.

Here are a few consequences I think we can take from what we’ve looked at.

First is responsibility and blame. If we’re affected in our genes by pollution, upbringing, economic development, stimulation, then we have to acknowledge that there are more people responsible for one person than the individual themselves.

Who is responsible? The parents? The wider community? The polluter? The nation? These are wider questions.

Second is liberty. The political philosopher Isaiah Berlin talked about negative liberty – the freedom from interference – and positive liberty – the freedom to do something. Science can help us think about both. To grow in an environment free from pollution is one thing, but to live in a stimulating environment, to have access to books, a good education, welfare creates the freedom to do more later in life.

Third, we might think about intervention: who is best suited, at what times, and where.

One of the most interesting conclusions from recent epigenetic studies is that much of this happens to us in the first few years of life.

So before we end I’d like to quickly look at where I think many of these studies lead: early intervention.

One of the main takeaways from all of this is how much the first few years of a child’s life – including the nine months of pregnancy – effect them for the rest of their lives. We usually think of education as the primary mode of improving a child’s environment, but it’s not enough.

A UK government report found that funding should be shifted from later to early interventions. And the children’s charity, the WAVE Trust, argues that governments should focus on preventing adverse childhood experiences like abuse, neglect, mental illness, etc.

And we already have some programmes like this – Sure Start in the UK and Head Start in the US – but I think we’re only just beginning to work out how to best utilise them.

Naomi Eisenstadt wrote on the LSE blog that, ‘The substantial success of the Sure Start scheme (in the UK) has been that the argument about the role government should play between birth and school is now won. … We no longer need to deliver more evidence that the pre-school years are vital to children’s development, and that provision of services for young children and families is critically important. … The acceptance that there should be provision for such services, and that government has a role in regulating and at least partly funding this, is now firmly in place’.

Programmes like Nurse Family Partnership (NFP) also assign nurses to low-income families for frequent visits.

But we also need to recognise this isn’t enough. A handful of visits and limited funding cannot make up for a history of generational poverty. We should treat having children like the most high-skilled job you can possibly do. We should offer extensive education and courses to pregnant couples and ensure the home environment is as good as it can be. We should extend parental leave and reorganise childcare around the discovery that the first few years of a child’s life are crucial.

Okay, I’ll leave you with a quote from the psychologist William James that has become even more pertinent in the light of epigenetics: ‘Compared with what we ought to be, we are only half awake. Our fires are damped, our drafts are checked. We are making use of only a small part of our physical and mental resources… Stating the thing broadly, the human individual lives far within his limits’.

And writer David Shenk describes it not as nature or nurture, genetics or environment, but genetics x environment.

It used to be thought that genetics were passed down like a blueprint – a precise guide to engineer the body. A code, a recipe maybe, a script. But genetics are more like a script that can be read differently depending on the context. As Nessa Carey has argued, different interpretations of Romeo and Juliet are made over time, in movies, stage, song, retellings in literature.

But I think we can go even further.

In turns out that actually, there’s so much in the box, but it interacts with so much outside of it in so many different ways that it is less a cage and more like a tardis, a party, an adventure, one that quite literally contain the ingredients for every chef’s kitchen, the words of every writer, the code of every computer programme in the world. That’s a lot to play with.

Sources

David Moore, The Developing Genome: An Introduction to Behavioural Epigenetics

Maurizio Meloni, Epigenetics for the Social Sciences: Justice, Embodiment, and Inheritance in the Postgenomic Age

Ian Deary, Intelligence: A Very Short Introduction

Rose Mortimer, Alex McKeown and Ilina Singh, Just Policy? An Ethical Analysis of Early Intervention Policy Guidance

Kim Ferguson et al, The Physical Environment and Child Development: An International Review

Nicky Hayes, Psychology in Perspective

https://www.madinamerica.com/2020/02/…

David Shenk, The Genius in All of Us

0 responses to “How the Nature/Nurture Debate is Changing”

buy cytotec without a prescription – orlistat 60mg generic buy generic diltiazem over the counter