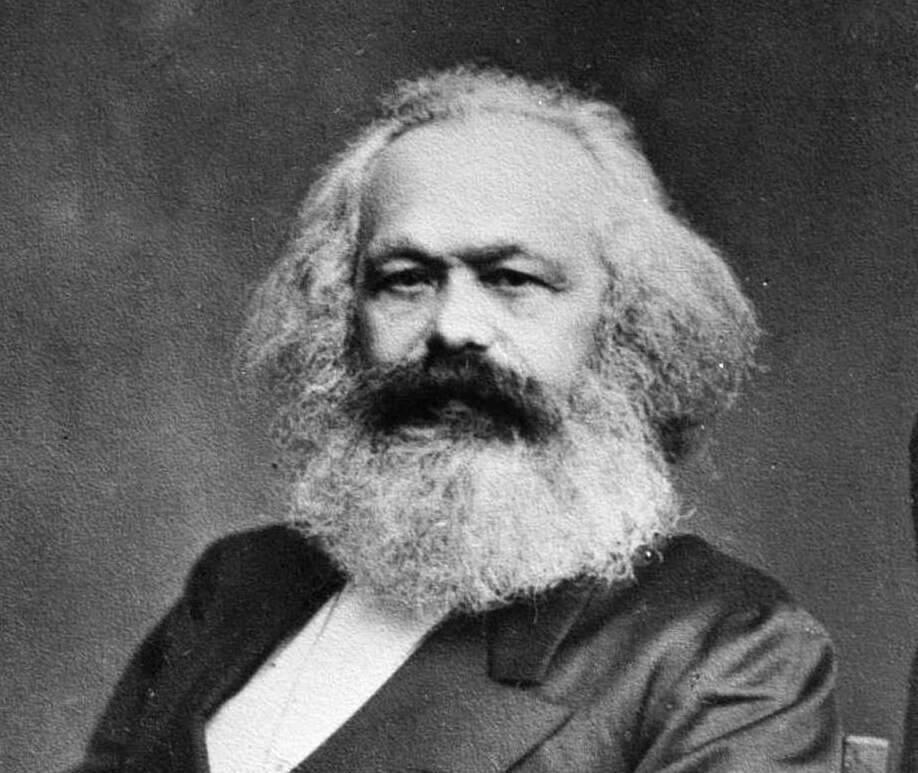

Karl Marx. One of – maybe the – most influential thinker in all of history. Has any other philosopher influenced not just ideas, but movements, actions, revolutions, the courses of entire governments, countries, and continents?

Understanding Marx is key to understanding the political and economic waters that have gotten us to where we are today, and leads to a big question: do we still live in Marx’s world?

He was a towering intellect. One contemporary said, ‘Imagine Rousseau, Voltaire, Holbach, Lessing, Heine and Hegel fused into one person . . . and you have Dr. Marx’.

Another said, ‘Marx himself was the type of man who is made up of energy, will and unshakeable conviction.’

Marx’s life was one of exile, secret societies, intense study, and poverty. Without judgement or bias, we’ll try and unpack his most important ideas, before returning to some common criticisms at the end.

Because many misunderstand Marx or at least don’t understand what he was truly saying. Many associate him with communism, about which he actually had little to say. What he really sought to understand was capitalism, commerce, markets, industrialisation and technological progress, and questions about what makes us truly human.

Marx absorbed and thought through all the trends and ideas around him. But what was most new in Marx was that it wasn’t thinkers that would change the world, but action by ordinary people.

To understand what that really means we have to go on a journey across history – from churches and fields to factories and cities. We need to understand where he was coming from.

Contents:

- Inverting Hegel’s Ideas

- Alienation

- The Economic Turn and Dialectical Materialism

- The Communist Manifesto (1848)

- Capital

- Use and exchange/Commodity

- Labour Theory of Value

- Money: Commodity Fetishism

- Surplus Value

- Forces, Relations, Bases, and Superstructures

- Technology and Productivity

- Class Struggle X Revolution

- Communism

- Conclusion

Inverting Hegel’s Ideas

Marx was a great synthesizer of the trends, movements, and ideas around him. He was born in 1818 in Prussia, modern day Germany, just after the French Revolution, Napoleon, and the spread of new liberal ideas about rights and freedom. New science, industries and factories were spreading across Europe. It was a time of unprecedented dynamic change.

Change is key to Marx. And to understand change there was no better person to turn to than Georg Hegel. He had argued that all previous moments in history were the unfolding of ideas, concepts, truth, dialectically, moving us forward.

I’m simplifying here, but for Hegel, this truth was an idea – idealism – images and words and concepts that led, slowly across history, to a greater understanding of the world and the universe, better political systems, more freedom.

The source of all of this, ultimately for Hegel, was god.

Hegel was still alive when Marx was young. But to young radical admirers, Hegel had become a dull conservative figure. He believed in progress, in rights, in freedom, but he also believed in order, in monarchy, and in religion. To a younger generation, these were oppressive forces.

A loose group of young intellectuals called the Young Hegelians emerged, who were influenced by Hegel but sought to go further than their old master. They were much more republican, liberal, and democratic.

Over time, they mostly got more radical, tending towards revolution rather than reform.

This was a century of reform and revolutions – minor and major, successful and failed, from America to Germany. The problem was many radicals in Europe didn’t really know what to replace the old aristocratic system with.

The Young Hegelians started with religion. They attempted to remove god from Hegel’s system. Two thinkers in particular – Bruno Bauer and Ludwig Feuerbach – were the most influential critics of religion of the time.

Hegel had argued that the unfolding of history was the product of God revealing himself through time. That we are all products of, the creation of, god, and slowly come to know the universe, science, the world better and so, in a way, return to god expansively.

But to the Young Hegelians, this positions ideas as kind of up there, above us, transcendent, unfolding down to us.

In other words, we imagine a god that is the creator of us, all powerful, that directs and guides us, but is also unreachable.

Feuerbach argued that when people did this, they were projecting. God is the sum total of the imaginative powers of our species projected onto some all powerful being. Instead, we should recognise this for what it is – our imagination. Religion is ‘the dream of the spirit’ he said. It actually disempowered us by displacing all our thoughts onto some supreme being, instead of attributing them to us as a powerful species.

In his book on Marx, political theorist Alexander Callinicos writes, ‘Feuerbach argued that Hegel had turned something that is merely the property of human beings, the faculty of thought, into the ruling principle of existence. Instead of seeing human beings as part of the material world, and thought merely as the way they reflect that material world, Hegel had turned both man and nature into mere reflections of the all-powerful Absolute Idea.’

In other words, by attributing our ideas to something outside of the world, particularly as supernatural religious phenomena, we alienated something within ourselves. It means our thoughts are not ours – it falsely presents them as coming from god – in the form of commandments, origin stories, church and political authority. It holds us back.

Fredrich Engels – Marx’s lifelong friend and collaborator – wrote that Feuerbach “placed materialism on the throne again”. He reminded us that ideas are the products of real human lives.

Bruno Bauer was even more radical. He argued that by asserting that the world was the product of god’s will, we justified the world as it was. Poverty? God’s will. King’s and despots? God’s will. Religion obstructed change.

From Bauer, Marx would develop his famous idea that religion was the opium of the masses. It says yes life is hard but that’s gods will and you’ll be rewarded in the afterlife, rather than encouraging a more progressive idea of history.

Now, here’s the important part. These young Hegelians were still Hegelians, meaning they were interested in ideas, they believed in the power of ideas. You just need the right ones, the better ones, the more truthful ones, to battle the old, repressive, wrong ones.

Another young Hegelian – the early anarchist Max Stirner – argued that bad ideas were spooks – bad thoughts that haunt the mind.

Marx criticised this approach. There are two significant early works here – On the Jewish Question published in 1843 and The German Ideology published in 1845.

It’s all well and good advocating for religious freedom, property rights, liberal ideas like freedom of speech– but all of it, in the end, leaves the real physical, material lives of ordinary people untouched.

For Marx that wasn’t enough because, ‘once the holy form of human self-alienation has been unmasked, the first task of philosophy, in the service of history, is to unmask self-alienation in its unholy forms. The criticism of heaven is thus transformed into the criticism of earth, the criticism of religion into the criticism of law, and the criticism of theology into the criticism of politics.’

Many – including Hegel and Rousseau before him – thought the state could be above society, neutral, general, negotiating fairly between different interests. But like the Young Hegelian critique of religion being too up there, Marx saw the same argument applying to the state.

The French and American Revolutions had made the claims that everyone was equal – in freedoms, before the law, in speech – and that this political equality emancipated people.

As the philosopher Leszek Kolakowski puts it in his book on Marxism: ‘purely political and therefore partial emancipation is valuable and important, but it does not amount to human emancipation.’

But what does emancipation really mean if some had nothing, were starving, had no land or means or resources, were taken advantage of?

Marx wrote that a liberal revolution would liberate only as, ‘an individual withdrawn into himself, into the confines of his private interests and private caprices, and separated from the community’. Instead, a social revolution could offer “human emancipation”.

He thought that the Declaration of the Rights of Man was a ‘big step forward, but is not the final form of human emancipation.’

He continued: ‘just as the Christians are equal in heaven, but unequal on earth, so the individual members of the nation are equal in the heaven of their political world, but unequal in the earthly existence of society’.

Politics must become concrete. Marx asks how can liberty just mean the right to not be interfered with, to acquire as much property as possible? What does this kind of liberty mean if you have nothing?

Marx writes: ‘None of the so-called rights of man, therefore, go beyond egoistic man, beyond man as a member of civil society, that is, an individual withdrawn into himself, into the confines of his private interests and private caprice, and separated from the community.’

In our time, all of the inaccessibility of politics, the talking in parliaments, the debates and the distractions, the dramas and sensationalist press, all pull away from the real material issues in people’s lives. This is what Marx was starting to get at.

He was beginning to, in his own words, invert Hegel – bring his ideas down to the gritty, dirty, physical, hard earth.

In The German Ideology Marx criticised his Young Hegelian contemporaries for believing that ideas can change the world. This was ideology – it distorted thinking and concealed the real issues.

Kolakowski writes: ”Ideology’ in this sense is a false consciousness or an obfuscated mental process in which men do not understand the forces that actually guide their thinking, but imagine it to be wholly governed by logic and intellectual influences.’

Again, it ignores material, sensory, physical life.

For Marx, freedom, progress, should be understood as “power, as domination over the circumstances and conditions in which an individual lives”.

Ridiculing idealism, ideology, the idea that ideas are dominant, Marx quips that, ‘Once upon a time a valiant fellow had the idea that men were drowned in water only because they were possessed with the idea of gravity. If they were to get this notion out of their heads, say by avowing it to be a superstitious, a religious concept, they would be sublimely proof against any danger from water.’

Summing up his critique of the Young Hegelians, Marx famously wrote: ‘The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.’

Alienation

The Romantics were another influence on Marx. They had argued, just a generation or so before him, that much about modern life, industry, and politics seemed to separate us from what they saw as a kind of natural wholeness.

In fact, Marx was a romantic in his early years. Like many others now and then, he wrote bad romantic poetry in his twenties. He came to the Romantics primarily through Hegel.

Hegel took the idea of unity and completeness from them. That a person should be able to develop themselves fully – three dimensionally – in relationship with the world around them, rather than feel disconnected from it.

In another words, Romanticism was about a striving towards completeness, towards being at home in the world.

The opposite of this was alienation, feeling estranged, disconnected from the world. Hegel said that individuals are in a “torn and shattered condition.”

Marx had a complicated relationship with this idea. He hated Hegel when he was young, accused him of mystification and obscurantism. But he came back to him, turned him upside down, and some say, as we’ll get to, abandoned him later on.

Either way, understanding alienation is fundamental as it was central to Marx’s development, and to many of the critiques of the modern world at the time and since.

So what is it? In his book on alienation, the philosopher Richard Schacht points to several definitions. According to one, alienation is ‘avoidable discontent’. Another is that it’s a feeling ‘which accompanies any behavior in which the person is compelled to act self-destructively.’ Another is that alienation points to ‘some relationship or connection that once existed, that is ‘natural,’ desirable, or good, has been lost.’

But the word that comes up most in the early Marx is ‘estranged’ – hinting at something that is no longer close.

It comes up in several ways. First money is alienating because it’s a stand-in for the real social relationships that are hidden underneath. It disconnects us from them and hides them. It becomes an ‘alien medium’ instead of people being the mediators – it separates us. Money is ‘men’s estranged, alienating and self-disposing species-nature. Money is the alienated ability of mankind’.

But labour is ‘estranged’ and alienated too. What workers do all day is for someone else on something for someone else. What they’re doing is out of their control, they are estranged from it.

Even their own bodies can become alien to them, as they’re forced to sell their own labour to stay alive. I like to think of it as a zombified state, on the factory line, doing something for no good reason except to afford to stay alive. Marx says the object the labourer produces ‘confronts’ as ‘something alien’ something ‘independent’ which stands ‘over and against’ them.

Kolakowski writes: ‘the alienation of labour is expressed by the fact that the worker’s own labour, as well as its products, have become alien to him. Labour has become a commodity like any other’.

On top of that, the division of labour means workers don’t even work on or understand the entire product. They’re divided into small, disconnected parts.

Marx writes: ‘Not only is the specialized work distributed among the different individuals, but the individual himself is divided up, and transformed into the automatic motor of a detail operation, thus realizing the absurd fable of Menenius Agrippa, which presents man as a mere fragment of his own body’.

Capitalism he says, converts the ‘worker into a crippled monstrosity.’

In On the Jewish Question Marx writes that while humans are supposedly equal in the political realm, in everyday life, the worker ‘degrades himself into a means, and becomes the plaything of alien powers.’

But – and here’s the key – according to Hegel we produce, project, and create the conditions of our own alienation as a species, so then by recognising that condition, we aim and work to overcome it. In other words, that progress arises out of the discontent of alienation itself. The bad becomes the good. Negativity drives us forward.

Kolakowski writes: ‘The greatness of Hegel’s dialectic of negation consisted, in Marx’s view, in the idea that humanity creates itself by a process of alienation alternating with the transcendence of that alienation.’

But, remember, Marx flips Hegel on his head. For Hegel that process was in the realm of ideas. For Marx, it’s material – it’s about the real conditions on the ground. Who is doing what, where, for who, in what ways. It’s how alienation confronts us in physical objects and processes like money, labour, in bricks and mortar. Kolakowski writes that the ‘true starting-point is man’s active contact with nature.’

And Petrucciani says that, ‘man is not only a natural sensuous being, but that specific being which self-produces itself through historical labor, and through the dialectic of estrangement and re-appropriation that characterizes it.’

In his early writings, Marx leant heavily on the concept of alienation. Some argue he abandoned it later on as it wasn’t a rigorous enough economic concept. Some – like Louis Althusser – argue that you can divide Marx into an early stage and a latter mature one. Others like David Harvey disagree. Petrucciani, for example says that while the early ideas become more ‘precise, reformulated, and filled with contents’, they’re never abandoned.

Callinicos writes that in the early work, ‘everything is built around the contrast between human nature as it is—debased, distorted, alienated—and as it should be.’

But this begs a question: how do you know what human nature should be? Surely everyone’s different? How can you get an ought – a moral claim about the world – out of an is – how the world is. And isn’t that idealism? Exactly what Marx sought to critique in the young Hegelians?

Marx’s problem with alienation can be imagined like this. You say capitalism alienates us. I say from what? You say from our natural selves. I say, like Adam Smith did, that capitalism is natural because human beings have a natural desire to trade, exchange and barter. You say it’s not natural to work in a factory all day. I say it’s not natural to farm or wear clothes.

This is called the naturalistic fallacy. That we place an arbitrary dividing line between something natural and something not natural, when in fact, everything comes from the earth, everything changes, everyone is different.

Marx tried to get around this problem with the concept of species-being.

For Marx, there isn’t a magical spiritual natural human essence that’s repressed by modern society. Instead, he imagines human society as a whole at any given time – everything humans are doing, arguing, being – and then contrasts individuals with that.

Marx wrote ‘the essence of man is no abstraction inherent in each single individual. In its reality it is the ensemble of the social relations’. Our essence as a species – our species-being – is the totality of our economic systems, cultures, politics, our history.

What he’s saying is that we have an idea of our species in our head, our relationship to it, what’s possible, and so we can become estranged and alienated from that.

A natural society isn’t something cooked up by philosophers – like Plato did in The Republic – designed, laid out, engineered. Society is a process that’s happening right now, it’s always happening, it’s about the development of it and how we relate to it.

The philosopher Lloyd Easton writes: ‘Marx particularly warns against establishing “society” as an abstraction over against the individual. The individual is a social being as the subjective, experienced existence of society.’

What you need then is to find a process that moves from alienation to a world in which everyone is connected to, has some control over, is served by our species-being. That the individual and society are not estranged, but in development with each other. And it’s around this time that Marx starts calling himself a communist.

In his Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 – a set of notes not published until 1932, and maybe the least catchy title of all time (if it was a Youtube title it would be something like ‘You wont believe these 10 secrets about wealth and wisdom) – Marx wrote that communism was ‘the positive transcendence of private property as human self-estrangement, and therefore as the real appropriation of the human essence by and for man; communism therefore as the complete return of man to himself as a social (i.e., human) being’.

Communism is the achievement of a “real community”. Under communism the “contradiction between the interest of the separate individual or individual family and the interest of all” will, according to Marx, be overcome.

Communism should be ‘the genuine resolution of the conflict between man and nature and between man and man – the true resolution of the strife between existence and essence, between objectification and self-confirmation, between freedom and necessity, between the individual and the species.’

Again, many argue the language of alienation and species-being was abandoned in the later works. Although most of the most influential commentators disagree. Kolakoski holds ‘there is no discontinuity in Marx’s thought, and that it was from first to last inspired by basically Hegelian philosophy.’

Social-being estranged, alienated, individual development repressed, then recognition, reconciliation, return, and emancipation.

The Economic Turn and Dialectical Materialism

For Marx, this new focus on material conditions, social relations, and physical life demanded a new method to understand capitalism. The old philosophy wouldn’t do. He’s fascinated by stuff not adequately captured by reflecting on ideas – wood, machines, protests. He borrows from Benjamin Franklin, for example, the notion that we’re a tool making species. That that’s what separates us from animals. Engels studies the working conditions in and around his father’s Manchester factory where he works. Both are working to bring philosophy down from the heavens.

For a long time, peasants in rural France and Germany had a traditional right to collect wood and twigs from the forest for their fires. But in the 1820s, as enclosures were happening and capitalism and property rights were expanding, laws were passed that ended these ancient rights.

Remember, Hegel and Rousseau had argued that the state, the government, could be the neutral representation of the general will, of all interests.

But in these new wood theft laws, Marx saw the obvious problem with that logic. The government, in banning the collecting of wood to keep warm by poor peasants, were taking the side of wealthy landowners over ordinary people.

In other words, the state became the vehicle for the propertied class who held economic power above all else, against ‘the poor, politically and socially propertyless.’

Engels later wrote, ‘I heard Marx say again and again that it was precisely through concerning himself with the wood-theft law and with the situation of the Moselle peasants that he was shunted from pure politics over to economic conditions, and thus came to socialism’.

It was in wood, in tools, in material that the truth of alienation could be found. If peasants and labourers were kicked off the land, if all of the countryside was enclosed in plots to farm, if the peasants had no tools or machines or money of their own, what would happen? They’d be forced to sell their own labour.

Here was a key and classic distinction – between those that had and those that had nothing. That the exclusive ownership of the tools, the means, of ownership and production was one of the keys to prosperity, to flourishing, to overcoming alienation.

This, again, was what was special about humans: we make tools – and that projection of an idea onto a material object that helps us to survive is key to our historical development.

Marx wrote, ‘The animal is immediately one with its life activity. It does not distinguish itself from it. It is its life activity. Man makes his life activity itself the object of his will and of his consciousness’.

We till, sow, fence, build, we enslave with chains, we engineer, we innovate. These are the things our lives are quite literally built around. They make up our material lives, they help us overcome our limitations, and they have a dynamic history.

Marx writes: ‘Men have history because they must produce their life, and because they must produce it moreover in a certain way: this is determined by their physical organisation; their consciousness is determined in just the same way.’

This is the basis of Marx’s materialism. That it’s our material, physical, sensory, social, productive life that matters. This may seem accepted, at least in large part, today, but when economics as a field was very new, all of this was very novel.

Most would have argued it was leadership or intelligence or great thought that determined the course of history and people’s lives – Napoleon a great military strategist, Plato the great philosopher, religion as the teachings of divine scripture. Marx was arguing to the contrary – the economy mattered most.

He wrote, ‘Men, developing their material production and their material intercourse, alter, along with this their actual world, also their thinking and the products of their thinking. It is not consciousness that determines life, but life that determines consciousness’.

This led him to the nascent field of economics. His brilliance would be to combine economics with philosophy. The newspaper he had edited in Germany had been shut down, he’d moved to Paris but had been kicked out, and now he was in exile in Britain. He spent months in the British Library pouring over Adam Smith and David Ricardo, recording whatever he could find, filling notebook after notebook.

He borrowed several concepts that we’ll come to, but he was immediately critical too. From his Hegelianism Marx believed everything was connected, that no man was an island.

Adam Smith – trying to understand the logic of the new commercially driven societies developing across Europe and America – started from the assumption of natural, individual self-interest. That ‘It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest’.

Marx hated this. He wrote ‘Production by an isolated individual outside society . . . is as much of an absurdity as is the development of language without human beings living together and talking to each other’.

He called them Robinsonades – that they assumed each person was a Robinson Crusoe on his own little island.

Callinicos writes, ‘Marx criticized the political economists because they tended to treat society as a collection of isolated individuals lacking any real relation to one another, so that “the limbs of the social system are dislocated’.

Another point that immediately dissatisfied Marx was their tendency to naturalise commercial society. Smith, for example, thought humans had a ‘natural tendencies to truck , trade, and batter,’ and so the market was the natural result of that.

Again, drawing on Hegel, Marx saw this as absurd. History changed across time.

He wrote – ‘Economists have a singular method of procedure. There are only two kinds of institutions for them, artificial and natural. The institutions of feudalism are artificial institutions; those of the bourgeoisie are natural institutions.’

They failed to see how there was nothing natural about them – human societies changed over time and human life was embedded in that societal context.

He wrote ‘the sensuous world around him is not a thing given direct from eternity, remaining ever the same, but the product of industry and of the state of society, and, indeed [a product] in the sense that it is a historical product, the result of the activity of a whole succession of generations, each standing on the shoulders of the preceding one’.

So this was how Marx proceeded: economics plus Hegel.

This idea of development, change, progress was the fashion of the day. In 1859, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species.

Marx later wrote ‘Darwin has directed attention to the history of natural technology, i.e. the formation of the organs of plants and animals, which serve as the instruments of production for sustaining their life. Does not the history of the productive organs of man in society, of organs that are the material basis of every particular organization of society, deserve equal attention?’.

The key was to understand how history unfolded as a system. It wasn’t that the lion and the deer or the worker and the capitalist were just in competition with each other, separate from each other, but that they were part of the same totality, the same system, and that system had to develop and change in a connected way dialectically.

He summed up his method like this: ‘My dialectical method is, in its foundations, not only different from the Hegelian, but exactly opposite to it. For Hegel, the process of thinking, which he even transforms into an independent subject, under the name of “the Idea,” is the creator of the real world, and the real world is only the external appearance of the idea. With me the reverse is true: the ideal is nothing but the material world reflected in the mind of man, and translated into forms of thought’.

The Communist Manifesto (1848)

Ok, there’s a final influence that we haven’t talked about much: the utopian socialists. These were varied movements and thinkers that emerged out of the Enlightenment ideal of progress, reason, and rights – that you could, in short, plan and design a society in which the needs of everyone could be met fairly.

The first was Francois-Noel Babeuf and his conspiracy of equals. Babeuf and his followers planned a coup during the French Revolution.

His Conspiracy of Equals planned to implement absolute equality in France, with the manifesto reading: ‘We aspire to live and die equal, the way we were born: we want real equality or death; this is what we need. And we’ll have this real equality, at whatever the cost’.

Spoiler alert, Babeuf’s conspiracy didn’t end well for him.

After the French Revolution there were Saint-Simonians and Fourierists.

Henri de Saint-Simon, distrusted democracy and the ‘mob’ but was an Enlightenment figure who believed society could be organised in everyone’s interests by men of science – that the state could technocratically plan society from the top down.

Charles Fourier on the other hand argued for rational communes organised around universal principles of psychology based on different personality types who would perform different jobs. Fourier was an eccentric and influential character who thought that ideal communes would have exactly 1620 people.

In Britain and then America, Robert Owen argued that our character was influenced by our environment, and so focused on education, reform, and cooperatives.

It was in Owen’s Cooperative Magazine in 1827 that the term socialist was likely used for the first time.

Finally, during the 1848 revolutions Louis Blanc argued for a ‘dictatorship of proletariat’ – without which the forces of reaction – foreign, aristocratic, monarchical, etc – would simply retake power. He wrote that the provision government should ‘regard themselves as dictators appointed by a revolution which had become inevitable and which was under no obligation to seek the sanction of universal suffrage until after having accomplished all the good which the moment required’.

What made all of these utopian? That you could conceptualise, idealistically, a rational planned commune or society – a utopia, and build it like an engineer designing a building. This ‘utopianism’ is what Marx rejected, but he still had one foot in this tradition.

In 1836, a group of German exiles in Paris and then London formed a Communist League of the Just. Marx joined them and they changed their name to the Communist League in 1847. Marx and Engels worked up a manifesto in 1848. At almost exactly the same time, by complete coincidence, a revolution broke out in Paris, which spread across Europe. These revolutions differed from place to place and were mostly liberal, but communism was just beginning to be taken more seriously.

The Communist Manifesto began with these now famous lines: ‘A spectre is haunting Europe — the spectre of communism. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre: Pope and Tsar, Metternich and Guizot, French Radicals and German police-spies.’

It continued: ‘The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles. Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary re-constitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes’.

The Manifesto is short, the best introduction to Marx you can find, pretty easy to read, written to be popular, and contains most of Marx’s most important early ideas, ending with the famous lines: ‘workers of the world unite, you have nothing to lose but your chains!’

In this early period Marx discovered the next big piece of his puzzle: the proletariat.

The bourgeoisie and the ruling classes could never be philosopher kings or just leaders in Plato’s or Hegel’s sense. No-one stands above and separate from the system like god looking down pulling the stings. The rulers are part of the system, they benefit from it, and so change has to come from elsewhere.

The proletariat – workers who must sell their alienated, estranged labour, who understand money as alienation, who work materially physically at the ground level – they are the force of change.

Petrucciani writes: ‘The proletariat is the class that lives through the most complete negation and which therefore becomes itself the subject able to deny all existing relations.’

This is why the call of the manifesto and the Communist League’s slogan was ‘Working men of all countries, unite!’ It was through this that Marx argued that the material conditions produce ideas, but then ideas can then influence material change.

Marx wrote ‘The weapon of criticism cannot, of course, replace criticism by weapons, material force must be overthrown by material force; but theory also becomes a material force as soon as it has gripped the masses.’

For Marx this wasn’t a moral argument. It was a historical, economic, dialectical one – a scientific one, a matter of forces. One class was getting richer, the other immiserated. Reactionary, aristocratic, monarchical, despotic governments were holding on to power across Europe and using increasing suppressive tactics. The continent was a pressure cooker. Marx believed that real revolution would come.

He wrote, ‘revolution is possible only in the periods when both these factors, the modern productive forces and the bourgeois forms of production, come in collision with each other. . . . A new revolution is possible only in consequence of a new crisis. It is, however, just as certain as this crisis’

The Manifesto brought all of these early themes together. However, while it was initially printed thousands of times it fell into obscurity for over twenty years before becoming more influential in the 1870s. And in those twenty years, crises and slumps would come, Marx kept thinking revolution would happen, but capitalism, railways, factories, steamships, and capitalist colonialism kept on spreading.

Trade unions organised for the first time, having been banned in many countries, socialists and anarchists formed the International Working Men’s Association in 1864 – the first International.

As he waited for revolution, Marx settled down to write his magnum opus – an analysis of the entire system.

Capital

At this point, Marx is juggling quite a few of the modern ideas around him. He knows he wants to ground his work materially, but he needs a concrete place to start.

Because for him, capitalism is dynamic, dialectical, in motion. He knows it’s transformative – all that is solid, he writes, melts into air.

For this reason, it’s important to remember that Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, or Das Kapital, or simple Capital, published in 1867 is not meant as a universal truth, but a snapshot of the European capitalism of the period, and the laws that Marx thinks emerge from it.

It’s a hugely ambitious, diverse book, full of references to literature, economic and philosophical ideas, the politics and culture of the period. Furthermore, it’s the first of three volumes, the second and third left in notes at the time of Marx’s death and compiled by Engels. And on top of that, there were meant to be six volumes, looking at land, the state, and the world market.

So its impossible to do it justice. Even most of Capital’s detractors don’t deny it’s a masterpiece. Agree with its conclusions or not, reading it and understanding it is indispensable for understanding the world we live in.

The themes are varied, but the most important are these: The question of what we value, and why, what gives things their monetary value. Labour, work – what motivates it, what’s at the root of it – capital and wealth – how they function and circulate – and the forces, movements, and contradictions that arise from the relationships between all of these.

The simplest way to think of what Marx is saying is this: that capital is an impersonal force – like gravity or meteorology or mathematics – with a life of its own.

Which is why Marx believed what he was doing was science. It wasn’t speculative in the sense of philosophers thinking up ideas in dusty studies. Capital is full of references to statistics, factory routines, rich and dense descriptions of how craftsman use different instruments, pamphlets and parliamentary debates. In this sense, it’s a very modern history – drawing on lots of evidence – of 19th century capitalism.

Marx is a man of the Enlightenment. Maybe one of the last great Enlightenment ‘system builders’, inspired by people like Newton – the idea that there are scientific forces, laws of motion, at play both in the natural world and in human societies.

The key for Marx was to search around, peel away, zoom in, interrogate – like astronomers and scientists do – to find the kernel, the secret hidden truth at the core of history.

Use and exchange/Commodity

So where does Marx begin? With something that’s all around us, that’s at the core of capitalism and all of our lives, that we cannot do without and may contain some secrets – the commodity.

What is it? It’s not obvious from the surface. They’re all so different. Theres almost nothing that unites them – a bus ticket so different from an iphone, a movie on DVD from a carefully crafted table. But Marx wants to find a concept that unites them all.

He realised that first, despite all of their differences – one being food, the other being a toy – they all have a use to someone.

All commodities are useful to someone – they have a ‘use value’.

But they also have a price, an ‘exchange value’.

What Marx finds immediately interesting is that neither of these are in the commodity. They can’t be found anywhere by simply examining it, taking it apart. They’re not inherent in it. So these values must come from elsewhere. Where?

He writes: ‘We may twist and turn a single commodity as we wish; it remains impossible to grasp it as a thing possessing value.’

Ok, everything has these price tags on. So that’s where the price comes from? But where does that come from? Maybe just from that use value – how useful we find each commodity.

But everyone finds different things useful. Diamond rings aren’t that useful but are expensive. Water is very useful but is cheap. I might hate Picasso and not find his art useful, but I wouldn’t turn down someone giving me a free Picasso painting. Because I know it’s worth something else.

So what is the mysterious exchange value based on? Marx points out that if I offer my three apples for your three onions there must be some metric, some common idea, that we’re basing our appraisal of what each thing is worth on. Why is that all commodities are comparable, if they have nothing else in common. We need a kind of ruler, a measuring tape, to understand them.

The simple answer is that the price tag, or the exchange value, is the cost of producing the item. A phone costs more than apple because it’s harder to make, it takes more infrastructure, more machines, more attention, more supply chains. If I sell you a cake I add up the cost of all of the ingredients.

But we get into an infinite regress. What determines the cost of the flour? The cost of the machines at the phone factory.

Marx says that at the base, what all of the commodities have in common is that they’re ‘products of labour.’ Commodities are ‘congealed quantities of homogeneous human labour’.

Commodities have values ‘only in so far as they are all expressions of an identical social substance, human labour’.

What he means is, yes my cake is based on the cost of flour, sugar, bowls, etc. But at every stage in their production, human labour produced each part. Even the factory walls at the phone machines were built by someone. The sugar cane had to be farmed. And so exchange value is the totality of all of that put together.

What Marx has immediately reached is the social value hidden behind the price tag. He says the object has a ‘phantom-like objectivity.’

In his great guide to Das Kapital, David Harvey writes, ‘Value is a social relation, and you cannot actually see, touch or feel social relations directly; yet they have an objective presence’.

We can bring this back to Marx’s idea about species-being. The value is something social, not individual, otherwise how would you ever get to a ‘fair’ price, a correct price, something to judge what your offer is made on. When you reject the price of something you often say something like ‘I could have made that for less than that’.

It’s a kind of hidden pattern, that connects me to the rest of society.

Like Hegel before him, it isn’t the thing that has an essential truth within, but it’s the relationships between things that matter.

Labour Theory of Value

Why does this matter? Value is a difficult idea to grasp, but it’s at the heart of almost everything. What we value is what we want more of, what we’re less likely to give away. Does how we value food differ from how we value friendship or democracy? Does value differ across different political and economic systems? If we can get to the bottom of how and why we value things we can use that as a basis for good arguments, philosophy, economics.

Marx came across the labour theory of value when reading the classical economists. The Scottish economist Adam Smith had first used the idea to describe how wealth came from production and industry rather than land, but that it came from capitalist investment and rent too. Then the British economist David Ricardo went further, arguing all value comes directly from the amount of labour time needed to produce a good. Ricardo, though interested in making sure land and industry was productive rather than wasted, didn’t take the next logical step in asking why, if labour creates value, did capitalists get rich and labourers stay poor? This was left to Marx.

Ok, so for Marx the more effort, the longer and the more difficult it is to produce something, the more people it takes, the more work and labour it takes, the more value it has.

But there’s a problem here. I might be very slow at making this, I might be bad at it, and a competitor might be better, quicker, and do it easier. Despite this, they will likely sell it at a higher price. So despite my labour time being higher, the outcome of my shoddy work is worth less. Surely this contradicts the labour theory of value?

For Marx, remember, value is a social phenomenon.

Things might have different use values – I might find this useful and you useless, but when we’re thinking about what its worth to society, to everyone, on average, what price we can get for it, what’s going on behind the scenes of the calculation?

Value, he says, is ‘socially necessary labour-time’.

Which is, Marx writes, ‘the labour-time required to produce any use-value under the conditions of production normal for a given society and with the average degree of skill and intensity of labour prevalent in that society’.

Petrucciani puts it like this: ‘Why socially necessary? Because, empirically, it can happen that a slow or incapable producer takes more time than a skilled and quick one to make the same object, say a chair. It would make no sense to say that an inefficiently produced chair is worth more, and thus Marx makes value equal to the average labor time which is needed to produce a given good’.

When we come together to judge value socially, we’re not interested in how long it took the individual manufacturer, say. Like walking along a line of market stalls selling the same products, we’re comparing them in the aggregate.

Marx writes: ‘The sum total of the labor of all these private individuals forms the aggregate labor of society. Since the producers do not come into social contact until they exchange the products of their labor, the specific social characteristics of their private labors appear only within this exchange.’

That value is socially necessary labour time forces producers into a single system. Each has to compare with one another, compete in the market, keep up with the latest innovations. If I take too long to make an inferior product it’s not going to sell, I’ll be undercut by the person on the market stall next to me.

This is precisely Marx’s method, that dialectical reversal, the turning of Hegel on his head. He’s gone and looked at the world materially, at the work, products, physical goods and factories, and from that empirical study taken lots of diverse heterogeneous exchanges and identified one single homogenous abstract concept: the labour theory of value.

He writes ‘concrete labour becomes the form of manifestation of its opposite, abstract human labour.’

And remember, labour itself has a value. If I employ ten workers I need to pay them enough to feed them, shelter them, make sure they have enough energy to work, then that amount paid them has to at least be the price of the product. Their labour goes directly into the product.

So the value of labour is the cost of maintaining it. If all of their food, getting to work, rent cost £100 and I produced 100 mugs, then all other things being equal, the mugs are worth £1 each.

Marx writes ‘if the workers could live on air, it would not be possible to buy them at any price. […] The constant tendency of capital is to force the cost of labour back towards this absolute zero.’

It’s only through the fact that labourers need things, that their ‘labour-power’ costs a certain amount, that the value of it is passed through into a commodity.

Money: Commodity Fetishism

Once there’s a universal measure that unites all commodities – the amount of labour embodied within them – then that unit, that appraisal, that number – can be represented or symbolised by something else – money.

Just like in Hegel, as one shape develops into another, the idea that an object can have an exchange value based in how much labour went into it, can develop logically into the idea of money to represent that value. Importantly, what we have here is movement, dynamism, development.

Marx writes: ‘the money-form is merely the reflection thrown upon a single commodity by the relations between all other commodities’.

But money does something else too. It measures value, but it also provides a kind of lubricant that enables exchanges to happen easier.

Money is both a measure of value and a ‘means of circulation’.

However, just like there’s a contradiction between use value and exchange value, between what an object’s useful is to you and how much it’s worth on the market, there’s also a contradiction within money itself.

It being a measure of value is different to it being a means of circulation. Because money can be saved up, hoarded, hidden and stashed. I could take it all, and there be no ‘means of circulation’ left.

Harvey writes: ‘what happens to the circulation of commodities in general if everybody suddenly decides to hold on to money? The buying of commodities would cease and circulation would stop, resulting in a generalized crisis.’

Sure you can hoard grain or save up X, but money is different. It’s more efficient, you can do more with it, everyone wants it, and it doesn’t spoil (as much).

It’s here for Marx that capitalism really starts to take off. People want money not just to pay for the necessities of life, but want it for it’s own sake.

Modern society, Marx writes, ‘greets gold as its Holy Grail, as the glittering incarnation of its innermost principle of life.’

Here we have accumulating, the root of some being able to lend money to others, to command interest rates, to get richer – we have what we calls primitive accumulation – the building of capital itself – large amounts of disposable money.

Petrucciani says: ‘The same attitude which appeared manic in the hoarder becomes iron clad rationality in the capitalist. The capitalist incarnates an insatiable desire for gain.’

Marx uses a formula. It used to be that a commodity would be exchanged for money to buy another commodity. Sell an apple to buy a chair. C (for commodity) – M (for money) – into C (for a new commodity).

But under capitalism that starts to reverse. Money can be used to buy commodities to sell for a profit, for more money. Instead of C-M-C we have M-C-M. Instead of a new commodity being the goal – selling the apple to get yourself a chair – money itself becomes the goal.

But Marx points out that if you’re swapping an apple for a chair they can both be worth the same and you get what you want out of the deal. He says, ‘Where equality exists there is not gain.’ But if you’re using money to buy commodities to make a profit, where does the extra money from?

Why would you do it if some gain wasn’t going to come from it? If C-M-C – cup for money to buy food is zero sum – each are worth the same, why is M-C-M positive sum? That the goal of the last M is more than the first M?

Marx says that under capitalism this appears as if a mystery.

He writes, ‘Capital is money, capital is commodities. By virtue of being value, it has acquired the occult ability to add value to itself. It brings forth living offspring, or at least lays golden eggs.’

Now, remember, all value must come from labour – people putting work into things. But when we start really using money, value becomes mysterious, as if taken over by money, as if money has magical powers and is the source of value itself, rather than being meaningless pieces of paper or chunks of gold.

Marx calls this commodity fetishism. He says there’s a ‘magic of money’ that conceals what’s going on underneath, that conceals the human work. Marx calls it a ‘riddle’ to be solved. With Marx there’s always something going on under the surface of things. He’s always moving from particular stuff to broader universal social phenomenon. Commodities he says are ‘sensuous things which are at the same time supra-sensible or social.’

He writes, ‘The mysterious character of the commodity-form consists . . . simply in the fact that the commodity reflects the social characteristics of men’s own labour as objective characteristics of the products of labour themselves, as the socio-natural properties of these things’.

Under capitalism, you can buy a fancy new shirt, but the objective conditions of production can be very hidden – sweatshops, unethical business practices, the devastation of the environment are all happening elsewhere, under the surface. But money can hide it. And commodities can appear on the shelves as if by magic.

Petrucciani: ‘Fetishism would be that attitude according to which commodities are endowed with value as if it belonged to them by nature, rather than because of the specific modality of their production.’

Commodities and money are hieroglyphs to be decoded and understood. They are curtains to be drawn back. There’s always something real, something understandable behind them. But we too easily forget this.

Marx writes: ‘It is however precisely this finished form of the world of commodities-the money form-which conceals the social character of private labour and the social relations between the individual workers, by making those relations appear as relations between material objects, instead of revealing them plainly.’

So what’s behind the curtain? How does the capitalist lay a golden egg? Why does the last M of the M-C-M magically contain more money that the first M?

Surplus Value

To uncover the secret, to peel back the layers, to dispel the illusion of commodity fetishism, we have to go somewhere philosophy doesn’t ordinarily tread. Marx says we have to enter ‘the hidden abode of production, on whose threshold there hangs the notice ‘no admittance except on business”. We have to go behind the factory doors.

It’s only here that the riddle of profit can be solved, how value can be miraculously created from nowhere, emerging like a golden egg. After all, value can only be made from people doing work.

If someone has a hoard, a stash, a windfall of money, what can they do with it to increase it? How can they increase that last M in M-C-M.

The capitalist searches around for a commodity that can expand in value and they find it, most obviously, in people themselves.

If I’m putting together a new product, out of wood, nails, wires – whatever – I need labour to help do it too. In this sense, labour-power is a commodity like any other. I can go to the market and buy my wood and I can go to the market, under capitalism, and hire labour.

Marx writes ‘The possessor of money does find such a special commodity on the market: the capacity for labour . . . in other words labour-power.’

To buy labour-power, the labourer must be free to sell it. They must be freed from servitude as peasants or slaves. They must then have nothing and need something, need a means of subsistence.

On the one hand, there are those who have access to estates with vegetable patches and fields and forests with wood, and then, after feudalism and slavery is abolished, we have those that are forced from the land, prohibited from collecting wood or using common land to grow food.

Marx writes: ‘Nature does not produce on the one hand owners of money or commodities, and on the other hand men possessing nothing but their own labour-power. This relation has no basis in natural history, nor does it have a social basis common to all periods of human history. It is clearly the result of a past historical development.’

Capitalism isn’t natural, but historical.

Now, here is the core of Marx’s argument. It is that labour-power is a commodity like any other. The labourer, wandering, looking for work needs a certain level of sustenance – food, shelter, welfare – that itself is provided by other labourers.

So the value or cost of labour-power is the value or cost of all producing all of the energy that energises and sustains that labour-power in the labourer. Meaning labour-power is comparable to any other commodity. It has a value and that value is determined by the labour theory of value – how much labour – food production, building shelter, collecting water – goes into energising the worker doing the work.

So the capitalist has capital, and they can spend that money on raw materials, supplies, and they can buy labour-power. They can combine it all together.

And Marx assumes that all of this is purchased at the correct price – that the value of everything is determined by how much labour went into making it. If it cost me $5 to get the energy/sleep/shelter to hammer the nails for one hour, that’s how much the labour-power is worth – $5ph.

That labour-power is combined with the wood and nails and then the capitalist sells. But again, he sells for a profit. He sells for more than the combined value of the labour-power and materials. The second M-C-M must be greater. Where is this extra, this surplus, coming from?

If the labour theory of value is right it can only come from labour.

So here’s the key.

Marx argues there is a gap between what it costs to sustain the labour over, say, a day, and what the capitalist gets out of the labourer in labour-power over the course of that day – and this is where surplus value comes from.

So in the first part of the day, as an example, the labourer is working in return for wages that cover the cost of sustaining them, or what Marx calls reproducing the labour, and in the second part of the day, the labourer is also covering the cost of sustaining the capitalists needs – their food and shelter. But it is here, Marx argues, that the capitalist can suck more value out of the worker than they’re being compensated for. That they can extract surplus value and make a profit.

He writes ‘Wherever a part of society possesses the monopoly of the means of production, the worker, free or unfree, must add to the labor time necessary for his own maintenance an extra quantity of labor time in order to produce the means of subsistence for the owner of the means of production’.

He argues that humans are just capital like everything else – material, muscle, machinery that can be bought, sold, or hired and their energy put to use. But that humans are a special type of capital – variable capital.

Humans are fleshy, muscly, malleable, mouldable and innovative things that are highly variable in the ways they can perform. So the capitalist can push a human to work harder, faster, differently, so as to squeeze more energy out of them.

Unlike nails or buildings, humans have more variability.

Machines, on the other hand – spinning wheels, hammers, lathes, factory equipment, buildings, metals and raw materials are ‘constant capital’ in contrast to ‘variable capital’. They move, spin, weave, hammer, and screw and a pretty constant steady inflexible rate.

So their value is the amount it costs to produce them and they can pass that value into the end product. The nails contribute to the total value of the table. But they cannot magically create value out of thin air – the value they transmit is constant.

New value must come from somewhere else. And it’s human labour that’s variable. It can change in speed, efficacy, length, strength, and dexterity.

Machines don’t vary, or go on strike, or get sick. They can’t be shouted at or disciplined or threatened. They are predictable. But if you can get more work out of a worker, or workers, then you can get more value into the final product. You can extract more surplus value.

Labour – variable capital – can be organised in different ways. They can be made more productive by dividing them up and getting them to perform smaller more repetitive tasks. Working out ways to improve efficiency. Their lunch breaks can be shortened or you could even provide meals if you think it will give them more energy. The point here is that it’s variable.

Harvey writes, ‘Surplus-value arises because workers labor beyond the number of hours it takes to reproduce the value equivalent of their labor-power. How many extra hours do they work? That depends on the length of the working day.’

As we’ll come back to, Marx spends many pages in Capital describing the English working class’s struggles to shorten the length of the working day. In the nineteenth century, the capitalist class in factories here in the Midlands of England did everything they could to lengthen them, to employ women and children in dirty unsafe factories, to cut costs, and to get the most out of labour that they possibly could. Marx calls them ‘small thefts’ of the workers time, the ‘petty pilfering of minutes’ or the ‘snatching of minutes’.

If one capitalist gets more end product – more tables say – from their workers in one day for the same amount of wages, they can either sell them cheaper than their competitors or for the same amount and keep more profit.

But the logic of capitalism – of competition – is such that if you don’t do it, your competitor will. This is fundamental to Marx.

He is not so dogmatic to argue that this happens all of the time, everywhere, or that capitalists are purposefully cruel and evil, only that there is a logic, a motivation, a force, that compels capital to operate in this or else someone else will do it elsewhere and make a cheaper product.

He writes, ‘The influence of individual capitals on one another has the effect precisely that they must conduct themselves as capital’. In other words, capital has a logic of its own, independent of individual capitalists.

There is downward pressure on wages and pressure to increase productivity not to get rich but just to keep up. Marx writes ‘the minimum wage is the centre towards which the current rates of wages gravitate.’

There might be some cultural expectations about the minimum wage, about safe working conditions, there might be regulations and oversight and nosy journalists here and there that push wages up slightly, but ultimately, there is a force putting downward pressure on wages.

If the capitalist pays the labourer more than all of his competitors out of the kindness of their heart then the end product costs more and they go out of business. If they shorten the working day while his competitors lengthen it and become more productive and so make a cheaper product, they go out of business. This is why ‘capital’ becomes an inhuman force, it has a magical effect on all those under its spell, forcing them into the logic of capitalist production.

Capital is full of literary references – Shakespeare and Romantic influences pop up everywhere.

Marx writes things like, capital has a “voracious appetite,” a “werewolf-like hunger for surplus labor”.

And ‘the vampire will not let go’ while there remains a single muscle, sinew or drop of blood to be exploited’.

And that “Capital is dead labor which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labor, and lives the more, the more labor it sucks’.

He’s calling machines ‘dead labor’ because their value comes from the living labour that was transferred into them. Das Kapital is a book of flows, of energy transfer, of how value moves dynamically through the world dialectically, how the workers’ ‘labour-power’ is alienated – taken from that – and how, as we’ll see, that flow of energy and value keeps moving inexorably from the worker into the capitalist class.

Forces, Relations, Bases, and Superstructures

Ok, we’ll return to that relationship between labour and capital – because that is the crux of it, that is the Hegelian contradiction, one pulls on the other creating discord – but we need to supplement it with a few more basic concepts.

Remember, Marx is trying to be scientific. He looks around and sees what happens a lot, then builds this from the ground up into broader concepts – specifically looking at nineteenth century capitalism.

Two main concepts he identifies are the forces of production and the relations of production.

The forces of production are the material, the buildings, tools, technology, instruments and factories of any given society.

And the relations of production are the social relationships that underpin the division of ownership and division of labour in any given society. The classes, the relationships between them, who owns and who doesn’t, how a society is organised.

Combined, these make up a mode of production.

In The German Ideology, Marx writes, ‘a certain mode of production, or industrial stage, is always combined with a certain mode of co-operation, or social stage, and this mode of co-operation is itself a “productive force”.’

Importantly, Marx points out how these modes of production have changed across history.

There was primitive communism, where tribes and primitive societies held resources broadly in common. There was slavery. Where one class is held in bondage to labour and another is free to trade them. There was a feudal mode – where peasants are tied to the land and produce their own means of subsistence but are obliged to provide for their lord in return for hypothetical protection. Then there’s bourgeois capitalism.

Each, he writes, ‘is replaced by a new one corresponding to the more developed productive forces and, hence, to the advanced mode of the self-activity of individuals.’

As contradictions appear one mode is replaced by another in a Hegelian way.

This is why Marx is a materialist, not an idealist. When he looks at the development of societies through history, it’s not the ideas of individuals that matter to the majority, but the type of economic system, the mode of production that has the biggest influence on how they and we live our lives. And classes – peasants, lords, slaves, proletariat, kings, bourgeoise – are at the root of this.

Callinicos writes: ‘Classes arise when the “direct producers” have been separated from the means of production, which have become the monopoly of a minority.’

But what about ideas? They’re everywhere, surely they have their place? Marx calls all of this the economic base, but argues that there is a superstructure over the top. So the base is the economic relations and forces of production – slaves, tools, farming, computers, serfs – the forces and the class divisions. And the superstructure arises from that in the form of norms, political assumptions, laws, even culture and art, and so on.

Marx writes: ‘The sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which rises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the social, political and intellectual life process in general. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness.’

The superstructure aims to justify the economic structure. Wages being kept low? We have to be productive or else China will beat us! Capitalism is harmful? Read Ayn Rand! I had no choice but to shoplift the baby food. I understand that but property is property – have you not read your Locke, young lady.

Marx writes: ‘The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas: i.e., the class which is the ruling material force of society is at the same time its ruling intellectual force. The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, consequently also controls the means of mental production, so that the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are on the whole subject to it. The ruling ideas are nothing more than the ideal expression of the dominant material relations, the dominant material relations grasped as ideas.’

And one of the biggest ideological superstructural myths, Marx says, comes from the bourgeoise having the power to tell tales about their thrift, ingenuity, creative genius – producing the idea that value comes from their endless revolutionising of technology.

Technology and Productivity

Like money, like commodities, we often see machines as magic, we fetishise them, think they can do things, create things, produce things out of thin air. We forget that they conceal social processes and relationships, physical lives underneath.

One compelling advantage Marx’s theory of history has is that it explains technological development. It explains why the industrial revolution seemed to take off at the same time as capitalism. Other theories – that innovations like the X are the result of genius individuals struggle to explain the wider historical trends of technological progress. Instead, technological development is fundamental to Marx.

We’ve seen that one way for the capitalist to extract surplus value is by trying to lengthen the working day, to improve the efficiency of labour by dividing workers up to perform smaller tasks, or to increase the intensity of work through discipline. In short, in finding ways of making labour more productive; by getting more out of workers in the same amount of time. But there’s another way of increasing productivity: technology.

All of the spinning wheels and water frames and engines of the industrial revolution were making labour efficient. You could make more jumpers in the same amount of time, employing fewer workers.

Now, importantly, the machines still need labour. They’re all built by people, need attending, need loading, needs maintenance, need correcting if something goes wrong. But they’re all what Marx calls ‘labour-saving devices.’ They make work more productive and so more surplus value can be extracted from the same amount of work.

Marx writes ‘machinery is intended to cheapen commodities and, by shortening the part of the working day in which the worker works for himself, to lengthen the other part, the part he gives the capitalist for nothing. The machine is a means for producing surplus value’.

Through technological innovation, we get more or better end product out of less labour-power. Less labour-power means lower wages have to paid. Competitors can then be undercut and more profit can flow to the innovative capitalist relative to the others in that particular industry.

Marx says, ‘The individual value of these articles is now below their social value; in other words, they have cost less labour time than the great bulk of the same article produced under the average social conditions’.

Now though, something interesting happens. The competitors either have to copy, keep up, innovate themselves, or go out of business.

When the competitors bring in the new machinery, the first capitalist can no longer undercut them, and they compete for the best price again, bringing the profits back down to where they were originally. So the first mover capitalist has the advantage when they innovate, but this doesn’t last long, and so the search for a new innovation, new technology continues.

Marx writes: ‘This extra surplus-value vanishes as soon as the new method of production is generalized, for then the difference between the individual value of the cheapened commodity and its social value vanishes.’

We can see the dialectical influence at play here. The particular actions of one lead to a generalised universal process that draws all in, which again returns to effect the particular individual, which returns to the generalised universal, and so on.

Marx then says: ‘capital therefore has an immanent drive, and a constant tendency, towards increasing the productivity of labour, in order to cheapen commodities, and, by cheapening commodities, to cheapen the worker himself’.

Again, this shows how capital becomes an inhuman, alien, vampire-like force. It compels people to act in a certain way, to search out labour-saving methods, to improve technology, to innovate, to compete, to try to underpay. And it compels others to follow or copy and keep up or go out of business. If you don’t search for productivity, for efficiency, your competitor will. Capitalism becomes a race against the clock.

It’s all about incentives within the total system, which is why Marx believed what he was doing was science in the same way Newton studied gravity – laws of attraction, forces that act on people pushing them to act in certain ways.

Even after the machine is paid for, there is an incentive to use it as much as possible unless it wears out, rusts away, gets replaced by better machines. Imagine the complexity and ingenuity of getting a water frame running or a steam engine working properly in a factory. Once it’s working 24/7, the reflexive impulse to find workers to man it as much as possible, to get as much from the machine as possible, must have been huge.

Marx writes, ‘competition subordinates every individual capitalist to the immanent laws of capitalist production, as external and coercive laws. It compels him to keep extending his capital, so as to preserve it, and he can only extend it by means of progressive accumulation’.

But notice a new stage of development. As they compete to keep up, we have larger, bigger, more technological advanced companies. As technology improves any industry requires more capital, more initial ‘outlay’ to even get started. The barriers to entry get higher. Some can’t keep up, can’t copy machines, can’t innovate and either go bust or get bought out and incorporated into the more successful bigger business. And importantly, fewer workers are needed to produce the same amount of product as they get replaced by machines.

Callinicos puts it like this: ‘Concentration takes place when capitals grow in size through the accumulation of surplus value. Centralization, on the other hand, involves the absorption of smaller by bigger capitals. The process of competition itself encourages this trend, because the more efficient firms are able to undercut their rivals and then to take them over. But economic recessions speed up the process by enabling the surviving capitals to buy up the means of production cheap.’

I think Marx answers a fundamental question about modernity here. Why does technology – which should save us all time – not make our lives easier? Better? Why are not all fishing and playing guitar while machines do our bidding?

Because machines, owned by a few, extract productivity from the rest. And the motivation to increase productivity is the desire to sell more and sell cheaper. So while capitalism makes some things cheaper, workers – and that’s a lot of us – are also commodities, subject to the same forces, same pressure of wages, on hours, on improving productivity. It’s a vicious circle.

Marx writes simply: ‘the machine is a means for producing surplus-value’.

He compares the old way of handicrafts, pointing to how the worker – like a woodworker – would ‘make use of a tool’, while in the factory ‘the machine makes use of him.’ Machines ‘dominate and soak up living labour-power’.

Technology is a double-edged sword. It can improve our lives but spurs competition, leads to concentration, increases barriers of entry, makes it harder for start-ups to compete, and can put more and more out of work. Where capitalism starts in small scale artisan workshops, it ends in highly advanced, labour trampling, surplus value extracting global technological conglomerates.

Capitalism preys on whatever it can find, sucking surplus into bigger piles, larger factories, seeking out new markets, anything that can be commodified. In short, all that is solid melts into air.

Class Struggle X Revolution

We too often think of history as causal or linear. That one thing causes the next like a row of dominoes. Dialectical thinking takes a different approach. Instead of a linear axis – calculator, microchip, computer, smartphone, say, – or slave, peasant, proletariat, bourgeoise, etc – we have a dialectical one where at any given moment in time – there’s a mutual relationship between elements and that when there is incongruence or incompatibility or friction between them transformation is forced – what Hegel called sublation.

What we’ve seen is how the interests of the proletariat and the bourgeoise are at odds – they contradict one another. One wants higher wages, the other wants lower, one wants to get home, the other wants higher productivity.

In the Grundrisse – an unpublished manuscript and notes of his economic thinking – Marx wrote: ‘The growing incompatibility between the productive development of society and its hitherto existing relations of production expresses itself in bitter contradictions, crises, spasms’.

The technology owned by the bourgeoisie is at odds with the wages of the worker. Machines put people out of work and create a reserve labour force. ‘The instrument of labour strikes down the worker’, Marx writes. Even if its transitional and more work is found eventually, there is a period of unemployment, a period of crisis for displaced workers.

Not only does this happen because of technology, but this can be good for the capitalist. If there’s a ‘reserve labour force’ then it makes it harder for workers to negotiate for higher wages because there’s always someone over there willing to do it for less just to work.

Capitalists get more and more value out of fewer and fewer workers. Workers are displaced and squeezed.

Now, the bourgeoise can keep revolutionising, building different machines, finding new markets, so new jobs might be created. So it’s not the case that absolute poverty for proletariat is inevitable – although it’s possible. What will happen is that as the bourgeoise acquire more and more capital, machines, technology and as many are put out of work, then the proletariat will be relatively immiserated.

Petrucciani puts it like this: ‘Marx can thus conclude by claiming that the ‘absolute general law of capitalist accumulation’ is to constantly produce, ‘in the direct ratio of its own energy and extent’, an excess of workers, a reserve army whose poverty increases as the power of wealth grows. These conclusions are of course very bleak, appropriately so because Marx aims to show (among other things) how capitalism is socially unsustainable’.

This relative immiseration means there’s more concentration into larger monopolies on the one hand and more fragmentation and discord on the other. Each are incompatible.

Engels wrote: ‘productive forces are concentrated in the hands of a few bourgeois whilst the great mass of the people are more and more becoming proletarians, and their condition more wretched and unendurable in the same measure in which the riches of the bourgeois increase.’

Map on top of this the unpredictability of capitalism, its booms and busts, crises, overproduction leading to crises, gluts, market instabilities, contractions, further bankruptcies and buy-outs, mass unemployment, and you have an explosive situation.

All of this is the apex of the argument in Capital: a tendency towards catastrophe.

A key concept here is that the rate of overall profit falls. If value and therefore profit comes from labour and there is increasingly less labour – less people – doing the same amount of work because there’s more and more machines, technology, infrastructure, and so on, the rate of surplus value being extracted decreases over time. Doing business gets harder. Being a proletariat gets harder still.

Again, a contradiction, an irony – that by improving productivity and investing more and more the capitalist class are sowing the seeds of their own destruction.

Marx writes: ‘What the bourgeoisie, therefore, produces, above all, is its own gravediggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable’.

What we have is a pressure cooker on a societal scale.