I know, another Jordan Peterson video. I’m sure you know who he is – the world’s current bestselling intellectual dark web megastar self-help guru – and I’m sure you’ve heard the criticisms – lobsters, feminism, postmodern neomarxism. And yes, we’re already inundated with critiques. But today, I want to look at something that I think has both been overlooked and is central to Jordan Peterson’s – and the wider self-help genre’s – philosophy: individual responsibility.

Almost all of Peterson’s arguments revolve around this idea of individual or personal responsibility. You could say it’s the meta-foundation at the core of his philosophy.

Today, I’m going to look at what individual responsibility really means, how we can understand it philosophically, and why it has its limits.

The argument I’ll draw out is this: that Peterson emphasises individual responsibility to an unreasonable degree, while discounting the necessity and power of social or collective responsibility. That each are two sides of the same coin.

But before we start, I will say this. 12 Rules for Life and Beyond Order are both great books. I learned a lot. There’s a lot of insight, many ideas to agree with, and much to disagree with.

I like the psychologisation of the biblical stories, there’s a great chapter on telling the truth, another one on assuming the person you’re listening to might know something you don’t. And I think he often gets unfairly caricatured. But he, in his turn, repeatedly straw mans and oversimplifies leftists and postmodernism in a way I think is, frankly, irresponsible.

But taking a thorough look at the idea of ‘individual responsibility’ helps us to understand why he almost has to do this.

So first, what does Peterson mean by individual responsibility?

12 Rules for Life, Beyond Order, and Peterson’s wider lectures have individual responsibility at their core. The books are replete with phrases like, ‘you must take responsibility for your own life. Period’, ‘each individual has ultimate responsibility to bear’, and ‘we must each adopt as much responsibility as possible for individual life, society, and the world’. Some of his lectures talk of the ‘sovereign individual’.

Now first, what follows isn’t an attack on individual responsibility. The concept is important, timeless, powerful, and Peterson has a lot of well-articulated and useful insight on how to take responsibility that people clearly want to hear. What I want to focus on is what’s left out.

It’s safe to say Peterson is a type of individualist. He focuses a lot on the archetype of the hero’s journey, of personal sacrifice, and focusing on yourself. Conversely, he’s sceptical, to say the least, of any collectivist ideologies, and ideologies more broadly.

He says, ‘Set your house in perfect order before you criticize the world’

Peterson writes: ‘Consider your circumstances. Start small. Have you taken full advantage of the opportunities offered to you? Are you working hard on your career, or even your job, or are you letting bitterness and resentment hold you back and drag you down? Have you made peace with your brother? Are you treating your spouse and your children with dignity and respect? Do you have habits that are destroying your health and well-being? Are you truly shouldering your responsibilities? Have you said what you need to say to your friends and family members? Are there things that you could do, that you know you could do, that would make things around you better? Have you cleaned up your life?’

To understand why this core foundation is one-sided and see what the other side of the coin is, we need to ask a really simple question: what does individual responsibility mean?

Throughout history, philosophers have interpreted responsibility in several ways. The concept has been discussed most frequently in philosophical debates about free will.

First, lets take it apart: response-ability.

Etymologically, the root of responsibility is to be ‘able’ to ‘respond’ to something. To react to a set of circumstances.

But its also often used as value judgement. One person might judge whether another was ‘able’ to ‘respond’ in a positive, helpful, useful, or moral way.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy puts it like this: ‘The judgment that a person is morally responsible for her behavior involves—at least to a first approximation—attributing certain powers and capacities to that person, and viewing her behavior as arising (in the right way) from the fact that the person has, and has exercised, these powers and capacities’.

So we have several key concepts: judgement, behaviour, power and capacities.

Let’s look at an example: shoplifting.

We might judge that it is immoral behaviour, and that the person had the capacity to know it was wrong and had the power to not do it.

Consequently, we might hold them responsible.

But what if we found out the person had dementia? We might say they didn’t have the capacity or the power to remember right from wrong, or to remember where they were.

Does this diminish their responsibility? Is this a mitigating circumstance?

It seems we’d judge them less morally responsible for the shoplifting than we would someone stealing jewellery because they want to be rich.

But if we find out the person had dementia we might say that they didn’t have the capacity to know right from wrong, and not find them morally responsible.

This is where free will comes in.

Many – like the existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre, for example – have argued that to be responsible for something, to be held accountable, you would have to have the freedom to have done otherwise, to have chosen more morally. That is, you have to be the cause of the action, inaction, or belief – not the dementia, say.

Let’s look at another example.

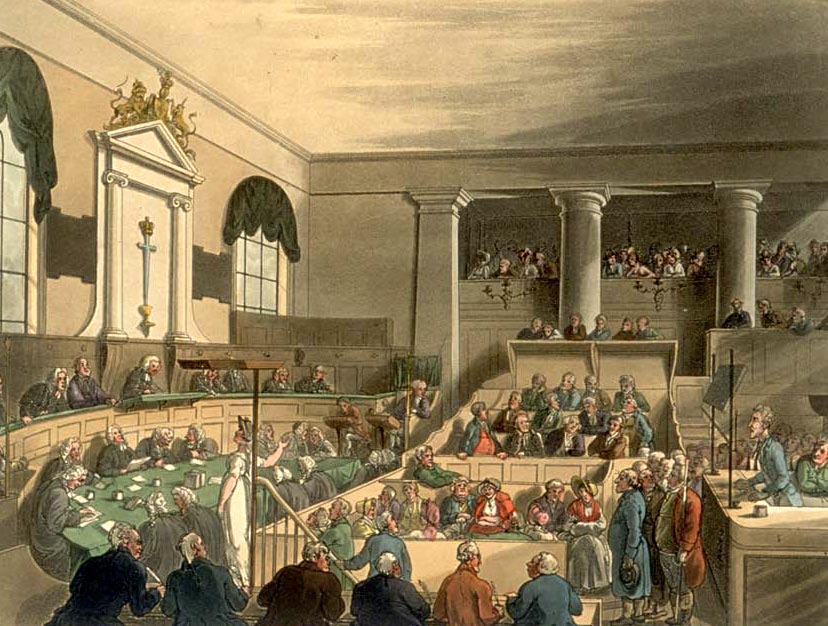

Take the jobless 16-year-old who assaults someone. If we’re on a jury, our initial inclination might be to hold them responsible as the cause, to blame them, to hold them accountable.

But imagine certain facts are slowly revealed. They came from a bad home, a poor neighbourhood, someone had been bullying them, or taunting them. Or even stealing from them. What if we found out they’d been blackmailed?

We might still hold the aggressor responsible, but maybe less so. Mitigating factors might lead us to sympathise with them because many factors contributed towards them becoming momentarily violent.

Let’s take one more example: the same child failing a maths test.

Were they responsible? Did they cause the failure? Of course, it depends on the context: they might not have studied enough, yes. But they might have a teacher who has treated them unfairly, a homelife that doesn’t encourage homework, they might have a learning difficulty.

We can see in a quote like this (from Book I, Rule III) that Peterson tends to discount contextual factors in favour of individual ones: ‘People create their worlds with the tools they have directly at hand. Faulty tools produce faulty results. Repeated use of the same faulty tools produces the same faulty results. It is in this manner that those who fail to learn from the past doom themselves to repeat it. It’s partly fate. It’s partly inability. It’s partly… unwillingness to learn? Refusal to learn? Motivated refusal to learn?’

This is the central question asked by many philosophers of free will and responsibility: if we are a product of our contexts, of our environment or circumstances, upbringing, education, or even of our genes, are we ever truly, ultimately, responsible for anything?

This position is called determinism, and it attempts to understand human behaviour in a scientific way.

As the psychologist B.F. Skinner wrote, ‘If we are to use the methods of science in the field of human affairs, we must assume that behavior is lawful and determined. We must expect to discover that what a man does is the result of specifiable conditions and that once these conditions have been discovered, we can anticipate and to some extent determine his actions’.

Skinner frames the problem of responsibly in a specifically modern and scientific context: science tells us that the entire universe is determined and everything has a cause. Why should human behaviour be any different?

He continues ‘small part of the universe is contained within the skin of each of us. There is no reason why it should have any special physical status because it lies within this boundary, and eventually we should have a complete account of it from anatomy and physiology’.

If determinism is true – if everything is caused – then this poses a problem for the idea of individual responsibly because we’re not really responsible for anything.

But surely the idea is meaningful in some way. Does this not leave something out?

The influential American philosopher Roderick Chisholm uses the following example. Take a flood destroying a dam. We might ask the following: what caused the dam to give? Poor construction? Political corruption cutting corners? Or was it constructed to the best of the builders abilities but the rainfall was unprecedented in a way no-one could have predicted? Maybe wrong materials were supplied by accident? Maybe someone sabotaged the damn? Maybe a river was redirected?

The question is where is the cause, where does responsibility lie?

Aristotle put it like this: that ‘a staff moves a stone, and is moved by a hand, which is moved by a man’.

Do we hold the staff responsible for moving the stone, or the hand? Maybe the muscles? The neurons? Maybe the man? Maybe he was ordered to move the stone by a despot? Maybe moving the stone was a by-product of another intention. Like simply standing up.

The point is this: when we look closely, we often don’t locate a single point of causation, find a single ultimate factor that we hold responsible. There are, of course, many factors, all partly responsible, all connected like a thread of causation; like a sequence or series of responsibility.

Historians approach topics in this way, like, for example, when they ask who was responsible for the Holocaust? Was it the product of Hitler’s will? Was it more structural? A German soldier in the forest shoots a Jew under orders. He’s been told they’re the enemy, they want to destroy Germany, it’s war, they would only starve later, etc. Do we intuitively hold the soldier less responsible than Hitler? Do we look at the economic factors that caused it, the propaganda, the history of antisemitism? Many things contribute to a single moment.

As the philosopher Robert Kane puts it, to retain individual freedom in a world where we’re so clearly determined we’d have to somehow be the ‘original creators of our own wills’ – when we can trace most of our behaviour backwards to things that have happened to us, to media exposure, to upbringing, education, to conditioning of some kind.

But some factors do seem to be more internal than others. If a man has every motivation you could think of, the education, the job market, but still refuses to find a job out of laziness, that seems to be an internal cause – that he is the one responsible for that lack of action.

This is the big question, the central question: how do we draw the line between internal and external causes?

Before we return to Peterson, lets visualise that line. There are interior causes – where we intuitively want to hold someone responsible – and external ones – where responsibility lies elsewhere. But oddly, this line isn’t just inside and outside the person. Genes lie outside the line. If someone is born with a condition that limits their mobility, say, we don’t hold them responsible for it.

But if lazy Billy has had a good upbringing, is smart, healthy, able-bodied, and there are plenty of jobs available, the responsibility we attribute to him, and the moral praise or blame that accompanies it, moves within the circle. We might say it’s laziness, say.

If there were no jobs in the area, or Billy’s mother was unwell and he had to look after her, we might move this factor outside, and we’d probably want to blame him less.

Let’s take one more historical example. When we ask what caused the First World War – what was responsible – the superficial reason we teach children is that Gavrilo Princip assassinated the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. But there were many other factors: colonial expansion, treaties between countries, nationalism. To say Princip was individually responsible for the war would be ridiculous.

Okay, lets return to Jordon Peterson.

Okay, so remember, Peterson’s central argument is about taking personal responsibility. And that’s a theme of self-help more broadly.

‘Set your house in perfect order’, he writes, ‘before you criticize the world’ (Book I, Rule 6).

And note the perfect here. It’s a very absolute word.

But again, before we go on, taking responsibility for your house, for what you can do, is perfectly good advice. Try your hardest, don’t be resentful, set your sights on specific goals – there’s some great advice here that can strengthen the internal circle. But the question is, what’s outside the circle? What do we do when there are factors outside of ours or other people’s control?

Is it not perfectly possible that the organisation of social life, of the state, of our economic systems, of our genetic inheritance, of our educational systems, have effects on individuals that are, shall we say, less than satisfactory, that at least could be improved on?

The extent to which Peterson idealises internal factors is illustrated most clearly in Book I, rule III: make friends with people who want the best for you.

In this rule, he warns us to think twice before helping someone in need for two reasons: that you might be helping for the sake of your own ego, and that the person doesn’t actually want help.

Peterson writes, ‘Are you so sure the person crying out to be saved has not decided a thousand times to accept his lot of pointless and worsening suffering?’.

He advises us not to assume the person is a ‘noble victim of unjust circumstances and exploitation’ and that there is ‘no personal responsibility on the part of the victim’.

In fact, in one passages, Peterson asks, ‘How do you know that your attempts to pull someone up won’t instead bring them—or you—further down?’

He imagines a team of ‘hardworking, brilliant, creative, and unified’ workers who are joined by someone ‘troubled, who is performing poorly, elsewhere’.

‘Does the errant interloper immediately straighten up and fly right? No. Instead, the entire team degenerates. The newcomer remains cynical, arrogant and neurotic. He complains. He shirks. He misses important meetings. His low-quality work causes delays, and must be redone by others’.

Not only that, Peterson assuredly declares that the ‘psychological literature is clear on this point’ when the single study he’s referenced could be interpreted in many ways. Training someone, for example, will always slow you down, helping someone is always difficult, but there are obvious reasons we do it. It’s an odd reference for a clinical psychologist to make.

And the message it supports and that runs through the chapter is worrying – it is essentially a scepticism at helping people.

Peterson says in Book I, Rule 6: ‘Don’t blame capitalism, the radical left, or the iniquity of your enemies. Don’t reorganize the state until you have ordered your own experience. Have some humility. If you cannot bring peace to your household, how dare you try to rule a city?’

Through Peterson’s lens people become atomised, so that responsibility comes from within.

He makes people individually accountable, unrealistically self-reliant, so that help must come from within without any reference to factors that might be too big for a person to overcome themselves. Many have already pointed to how this message falls flat in the context of endless historical struggles: have you thought about looking at your own life Mandela? Are you sure the British are the problem Gandhi, maybe start by cleaning your room? Yes, Doctor King, you might want voting rights but you are a serial adulterer. Yes, you might want this $100,000 life-saving cancer drug but have you thought about working harder to pay for it? Yes, the Nazis are coming but aren’t there plenty of places to hide if you make the effort to think it through?

Again, I’m not trying to belittle the idea of individual responsibility – you could point to any number of counter-examples where it is applicable. I’m only trying to show where it’s not, where it seems to leave something bigger out.

The question is not just how do we hold individuals responsible for changing themselves, but how do we arrange social, cultural, and economic life in the way that individuals are most likely to be able to change themselves.

As Peterson himself says, ‘perhaps the game you are playing is somehow rigged’. But then he can’t avoid the temptation of adding: ‘perhaps by you, unbeknownst to yourself’.

So what do we do when faced with problems outside the circle, when the game is rigged, when there are no jobs, when the Nazis are closing in, when we’re denied our rights? What do we do when someone or something else really is responsible?

We look to something bigger.

Some things, in a broad sense, are clearly what we might call social, cultural, or collective in some way. Language, for example, etiquette, fashion, the news cycle, our political systems. The list goes on. These phenomena transcend the individual; they require, by their very nature, wider agreement and consensus, at least loosely.

These things make up what philosopher Manuel Vargas has phrased the ‘social scaffolding of moral responsibility’, or the ‘moral architecture’ – the cultural and social landscape that changes across cultures and throughout history; the external factors that might encourage or discourage certain behaviours.

Take etiquette. We can hold someone morally responsible for being rude, for saying racist or sexist things, for giving a Nazi salute, for constantly interrupting in a conversation, but the person has to know that the statement or action is considered wrong. If they come from another country, for example, we might say ‘they were unaware’.

As Peterson himself says, ‘What we deem to be valuable and worthy of attention becomes part of the social contract; part of the rewards and punishments meted out respectively for compliance and noncompliance; part of what continually indicates and reminds: “Here is what is valued. Look at that (perceive that) and not something else. Pursue that (act toward that end) and not some other.”’

In other words, the external factors that motivate us to speak or act in specific ways are culturally and socially constructed, and we can be aware or unaware of them.

Sometimes, though, it’s the social and cultural scaffolding itself that some might consider wrong, unethical, and in need of changing: someone in Germany might not have wanted to give the Nazi salute, even though it was considered the responsible thing to do. A slave might not want to use the phrase ‘yes master’.

Some of these things are clearly social. The acceptability of them, the motivational power of the tyranny of the majority, external pressures, are all larger than any one individual. Language is a great example. We’re partly responsible for what we say but the tools, the structure, the language itself is a broader social phenomenon. Culture is another example; so are roads and infrastructure, moral norms and political systems.

The central point, if we return to our internal/external circle, is this: some of the factors that contribute towards how people act, are external, they’re larger than any one person, but they can also be changed. The question is how?

Take the campaign for women’s suffrage. It was an external factor that women couldn’t vote and so had impediments to living their lives in certain ways. The social scaffolding of moral responsibility expected women to act in certain ways, dress in a certain way, look after the home, not work, not get an education, not vote, not drive. To say a women was responsible for not being able to advance her career in this context is like saying Gavrilo Princip was responsible for World War One. There are larger structural factors.

And those factors are often so socially entrenched that there’s only one way to overcome them: collectively. Socially. Through networking, campaign building, coalition building, through critique, through, dare I say it, ideology.

Instead of acknowledging this Peterson writes: ‘It is impossible to fight patriarchy, reduce oppression, promote equality, transform capitalism, save the environment, eliminate competitiveness, reduce government, or to run every organization like a business. Such concepts are simply too low-resolution’.

But for collective action like the civil rights movement, or even building a community bridge, low-resolution, at first at least, is necessary. It enables us to come together, for alliances, enables us to delineate the outline of the problem, to find a broad agreement that unites a group pursuing a goal despite their disagreements. Not every suffragette agreed on the course of action, not everyone agreed where the bridge should be, not everyone agrees on the values, on the history, but the low-resolution goal in many great social justice movements was clear: to take a large external impediment and unite into a body powerful enough to address it.

In Book II, Rule IV Peterson recommends that we ‘notice that opportunity lurks where responsibility has been abdicated’.

Great rule. He advises us to ‘Organize what you can see is dangerously disorganized’.

He writes, ‘what is the antidote to the suffering and malevolence of life? The highest possible goal. What is the prerequisite to pursuit of the highest possible goal? Willingness to adopt the maximum degree of responsibility—and this includes the responsibilities that others disregard or neglect. You might object: “Why should I shoulder all that burden? It is nothing but sacrifice, hardship, and trouble.”’

Does this not contradict Peterson’s advice to think twice before helping others? Does this not include the highest possible social goals? Does it not require forming groups to tackle the dangers and problems too big for any one of us to address?

This leads us to next time: Book II, Rule 6 is ‘renounce ideology’. In part II of this two-part series, I want to look at what ideology is, and why we need it to pursue those things that transcend the individual. We’ll see how Peterson’s critique of ideology is limited by his partial, one-sided analysis of responsibility, and how a closer look at both draws out even more contradictions in Peterson’s worldview.

For now I’ll leave you with words from the man himself:

Align yourself, in your soul, with Truth and the Highest Good. There is habitable order to establish and beauty to bring into existence. There is evil to overcome, suffering to ameliorate, and yourself to better.

Sources

Joel Fienberg and Russ Shafer-Landau, Reason and Responsibility: Readings in Some Basic Problems of Philosophy

Michael McKenna, Power, Social Inequities, and the Conversational Theory of Moral Responsibility

Catriona Mackenzie, Moral Responsibility and the Social Dynamics of Power and Oppression

Manuel R . Vargas, The Social Constitution of Agency and Responsibility: Oppression, Politics, and Moral Ecology

Moral Responsibility – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Jordan Peterson, 12 Rules for Life

Jordan Peterson, Beyond Order

Michael Katz, The Undeserving Poor: America’s Enduring Confrontation With Poverty

0 responses to “Why Jordan Peterson is Wrong About Responsibility”

cheap misoprostol 200mcg – diltiazem us diltiazem oral