Jordan Peterson is famously critical of ideology. He has a particular distain for Marxism, Stalinism, Nazism, Postmodernism, Feminism, in fact, any -ism.

Instead, he argues, the individual is sovereign, ideology should be renounced, and that, ‘If we each live properly, we will collectively flourish’.

Today we’re going to examine Peterson’s charge against ideology, ask what ideology really is and why it’s misunderstood, what Peterson’s ideology is, what his ideology leaves out, and finally, see why we need ideology.

So what does Jordan Peterson mean by ideology?

Rule six of Peterson’s book, Beyond Order: 12 More Rules for Life, is ‘Abandon Ideology’.

Drawing on the Russian novelist Dostoevsky, Peterson interprets ideology as ‘rigid, comprehensive, utopian’, and predicated on a few ‘apparently self-evident axioms’.

An -ism theorist, he argues, ‘generates a small number of explanatory principles of forces’ that can supposedly ‘explain everything: all the past, all the present, and all the future’.

An ideologue, he continues, ‘grants these small number of forces primary causal power, while ignoring others of equal or greater importance’.

The result of this is that ‘an ideologue can consider him or herself in possession of the complete truth’.

Peterson writes, ‘They adopt a single axiom: government is bad, immigration is bad, capitalism is bad, patriarchy is bad. Then they filter and screen their experiences and insist ever more narrowly that everything can be explained by that axiom. They believe, narcissistically, underneath all that bad theory, that the world could be put right, if only they held the controls’.

He says that, ‘there is no claim more totalitarian’.

While warning against the dangers of totalitarianism and the idea of an unreachable ‘promised utopia’, he also includes those who ‘maintain faith in the commonplace isms characterizing the modern world: conservatism, socialism, feminism, (and all manner of ethnic- and gender-study isms), postmodernism, and environmentalism, among others’.

Notice he includes conservatism too.

But we’ll ignore the seeming contradiction for a moment because I want to be charitable. Let’s look at how Peterson’s critique has three parts: that ideology is utopian; ideology is simplistic; and ideology is driven by resentment.

First, utopianism is unachievably idealistic. He writes, ‘let us not get too grandiose. We can design systems that allow us a modicum of peace, security, and freedom and, perhaps, the possibility of incremental improvement. That is a miracle in and of itself’.

The second charge is that ideology is too ‘low-resolution, simplifying the world and ignoring the nuance while focusing narrowly on those small number of explanatory forces’.

Explanatory forces might be ‘the patriarchy’, ‘the rich’, the ‘oppressors’, etc. He writes that ideologues’ ‘use of single terms implicitly hypersimplifies what are in fact extraordinarily diverse and complex phenomena’.

For Marx, for example, Peterson says everything can be explained by ‘running it through a Marxist algorithm’. He says this is attractive to ‘faux-theorists’, ‘incompetent and corrupt intellectuals’, ‘smart but lazy people’, ‘pseudo-intellectuals’, and ‘fundamentalists’. He says they’re ‘monotheists’.

Instead, Peterson says, ideology should be renounced and, ‘All such problems require careful, particularized analysis, followed by the generation of multiple potential solutions, followed by the careful assessment of those solutions to ensure that they are having their desired effect. It is uncommon to see any serious social problem addressed so methodically’.

Finally, Peterson charges ideologues with being motivated by the resentment of the rich or powerful rather than by sympathy for the poor or oppressed. He says, ‘when someone claims to be acting from the highest principles, for the good of others, there is no reason to assume that the person’s motives are genuine.’… ‘When it’s not just naïveté, the attempt to rescue someone is often fuelled by vanity and narcissism’.

So for Peterson, ideologues are wrong for three main reasons:

1. They oversimplify the world (an empirical problem)

2. They’re overly utopian and optimistic (a possibility problem)

3. They’re motivated by resentment (a motivational problem)

We’ll return to this at the end. But first, what do philosophers say ideology is?

Okay, so what is ideology? It’s most commonly associated with Marxism, the far-left or far-right, maybe with Nazis, maybe with the Soviet Union, sometimes with Black Lives Matter. A quick glance is enough to tell us it’s an ambiguous term.

As a concept, ideology is resolutely modern. It emerged as a result of the English, American, and French revolutions, the scientific revolution and the rigorous ‘study’ of the world, and could only be communicated because of the rise of the printing press.

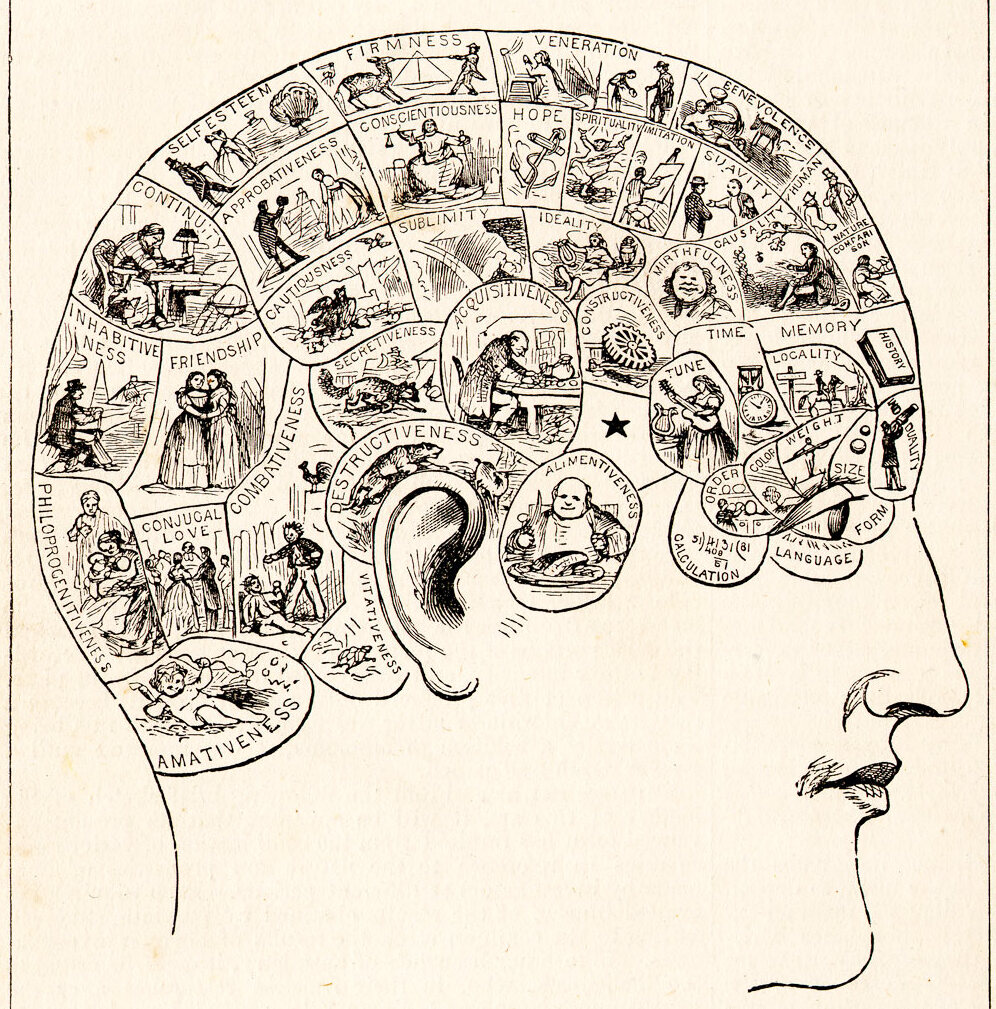

At its simplest, an ideology is a worldview, a system of belief, a map of meaning.

But when you look at how philosophers have defined the term, it’s difficult to find much agreement.

Frankfurt School theorist Theodor Adorno defined ideology as simply, ‘An organization of opinions, attitudes, and values-a way of thinking about man and society’.

Political Scientist Karl Loewenstein argued that it is, ‘A consistent integrated pattern of thoughts and beliefs explaining man’s attitude towards life and his existence in society, and advocating a conduct and action pattern responsive to and commensurate with such thoughts and beliefs’.

Philosopher Martin Seliger has written that ideologies are ‘Sets of ideas by which men posit, explain and justify ends and means of organised social action, and specifically political action, irrespective of whether such action aims to pre- serve, amend, uproot or rebuild a given social order’.

Some have defined it critically, like political scientist Giovanni Sartori, as ‘typically dogmatic’ and ‘rigid and impermeable’.

But in an overview, John Gerring has argued that the definition is so contested that the different definitions really only have one thing in common: coherence.

Ideologies are sets of ideas or values that are defined by their coherence and consistency. They are integrated into a system of logic. Ideologies often guide thought, language, behaviour, and action. They’re a rough map that organises a view of the world, motivating us to perform actions, make arguments, make value judgements, and behave in certain ways. In this way, we might have an ideological approach to cooking or sports as much as politics and morality.

But one misunderstanding many people have is the idea that ideology is anything but reality, the present, or the status quo. Many often miss how the present has an ideological basis as much as Marxism or Feudalism or post-feminist-anarcho-jupiterism.

As Adorno wrote, ‘reality becomes its own ideology through the spell cast by its faithful duplication’. It might be contested and vary from place to place – liberal, neoliberal, nationalist, federalist – but our worldviews are the product of ideologies theorised by thinkers like John Locke, John Stuart Mill, Montesquieu, the American Founding Fathers – the list goes on. The ideologies we live in become more difficult to see because like fish in water, we swim in them.

So if ideology is just a coherent and consistent set of ideas we might say that Peterson’s criticism is not with ideology, per se, but with dogmatic ideology – ideas that become too rigid. So let’s look at the coherent and consistent set of ideas guiding behaviour in Peterson’s ideology – what I’ll call Mythic Conservatism.

As I examined in an earlier video, the foundation of Peterson’s ideology is the sovereignty of the individual as primary, and, as we’ll look at now, a type of Judeo-Christian mythic structuralism. Alluded to throughout 12 Rules for Life and Beyond Order, and more thoroughly argued for in Maps of Meaning, Peterson’s ideology goes something like this.

He says, first, ‘arrangements must be made for our provisioning with the basic requirements of life’.

We need food, shelter, water, etc…

Second, he says, ‘It is worth considering more deeply just how necessity limits the universe of viable solutions and implementable plans’. This is because they:

1. ‘must in principle solve some real problem’

2. ‘must appeal to others’ – value something so others benefit, not just good for me

3. Work ‘for me, my family, and the broader community’

4. Must work today, tomorrow, next month, next year

The idea is that, ‘These universal constraints, manifest biologically and imposed socially, reduce the complexity of the world to something approximating a universally understandable domain of value’.

He continues, ‘The fact of limited solutions implies the existence of something like a natural ethic—variable, perhaps, as human languages are variable, but still characterized by something solid and universally recognizable at its base’.

So the way we, as humans, approach problems, relationships, and the world, is limited. If it is limited it becomes natural, solid, in tune with our biology and social life, and so becomes universal. Because it is repeated over and over by past generations, because it works and there are no alternatives, this ‘natural’ ethic emerges in rules, in myths, in our every day behaviour, in stories and film.

Remember that Peterson’s primary critique of ideology is that it is dogmatic. The dictionary definition of dogmatic is ‘inclined to lay down principles as undeniably true’.

Okay, but what are some of these limited and universal rules?

First, we can see them in the ten commandments, which, Peterson writes, are ‘the most influential Rules of the Game ever formulated’ – the ‘bedrock of our culture’.

He writes, ‘it is worthwhile thinking of these Commandments as a minimum set of rules for a stable society—an iterable social game’.

The rules can be seen more broadly throughout Christianity, which as a doctrine ‘elevated the individual soul, placing slave and master and commoner and nobleman alike on the same metaphysical footing, rendering them equal before God and the law. Christianity insisted that even the king was only one among many’.

‘Christianity made explicit the surprising claim that even the lowliest person had rights, genuine rights’.

In Christianity we can see the development of the sovereign individual, but more than this, we see archetypes that are repeated throughout history in universal myths like the hero’s journey, the importance of sacrifice, and the idea that order is masculine and chaos is feminine.

Peterson writes, ‘these ideas are also encapsulated and represented in the narratives, the fundamental narratives, that sit at the base of our culture. These stories—whatever their ultimate metaphysical significance—are at least in part a consequence of our watching ourselves act across eons of human history, and distilling from that watching the essential patterns of our actions. We are cartographers, makers of maps; geographers, concerned with the layout of the land. But we are also, more precisely and accurately, charters of courses, sailors and explorers’.

Peterson is describing a type of structuralism – that there are universal structures that explain and, at least somewhat determine, human behaviour. The structure is part of our very make-up. And myths, he says, ‘speak to something we know, but do not know that we know’.

The Golden Rule, for example – ‘do to others what you would have them do to you’ – is found repeatedly across cultures and throughout history.

The exodus story is archetypal, he says, because it cannot be improved upon. ‘Let my people go’, hardship, tyranny; it’s a narrative that’s been identified with throughout history, for example, in slave-owning America.

Or the idea or image of a dragon – the worst imaginable creature – guarding a ‘great treasure’ – that can only be slain with heroic courage. He discusses the Hobbit, Pinocchio, The Lion King, and Ironman all conforming to these structural myths.

Okay, so first: what Peterson describes is ideological. If we return to our definitions of ideology it fits the bill.

For example, in a comparative study of ideology, political scientist Mostada Rejai has said that ideology is ‘An emotion-laden, myth-saturated, action-related system of beliefs and values about people and society, legitimacy and authority, that is acquired to a large extent as a matter of faith and habit. The myths and values of ideology are communicated through symbols in a simplified, economical, and efficient manner’.

Sound familiar? So critiquing ideologues and ideology while advocating for a type of Judeo-Christian structuralism is a contradiction, at best, and hypocritical too. And in some places the cognitive dissonance is comical: Peterson critiques ideologues for being dogmatic then writes that, ‘It is therefore necessary and desirable for religions to have a dogmatic element. What good is a value system that does not provide a stable structure? What good is a value system that does not point the way to a higher order? And what good can you possibly be if you cannot or do not internalize that structure, or accept that order—not as a final destination, necessarily, but at least as a starting point?’.

This is despite everything Peterson says in the chapter to tell us to ‘renounce ideology’, about it being too low-resolution, simplistic, ‘fundamentalist’, and being run through a hyper-simplified algorithm. It’s no different just because his principles are found ambiguously in stories in the past.

This is why Peterson’s a conservative. Because his ideological ideas, those dogmatic principles, are found in the timeless wisdom of the past. They’re unchanging, limited, eternal, and so don’t really need improving on. He’s a type of Burkean conservative, named after the father of modern conservatism, Edmund Burke. Burke wrote that conservatism is an ‘approach to human affairs which mistrusts both a priori reasoning and revolution, preferring to put its trust in experience and in the gradual improvement of tried and tested arrangements’.

As Peterson writes, ‘It is the reality of this natural ethic that makes thoughtless denigration of social institutions both wrong and dangerous: wrong and dangerous because those institutions have evolved to solve problems that must be solved for life to continue. They are by no means perfect—but making them better, rather than worse, is a tricky problem indeed’.

There’s an odd tension here. On the one hand eternal, natural, universal, limited rules are to be found in the past, while on the other hand, there is the acknowledgement that they might need improving and changing.

If structuralism is the idea that there is a universal, eternal, unchanging, limited set of rules to human experience and behaviour, post-structuralism argues that these rules are in fact unstable, subject to change and reinterpretation. And Peterson’s limited rules seem so ambiguous, so diverse and varied across cultures and history, that it seems questionable to call them limited at all.

As Peterson himself writes, ‘Our knowledge of how to act in the world remains eternally incomplete—partly because of our profound ignorance of the vast unknown, partly because of our wilful blindness, and partly because the world continues, in its entropic manner, to transform itself unexpectedly’.

He continues that, ‘Human beings are, after all, seriously remarkable creatures. We have no peers, and it’s not clear that we have any real limits’.

As he acknowledges, ‘liberal types tend to determine how what is old and out of date might be replaced by something new and more valuable’. Or, ‘we can do anything we want now, as a species’.

So again, there’s a tension here. On the one hand he’s dogmatic, while on the other, the rules and archetypes he examines are broad and ambiguous enough to be almost infinitely reinterpretable. The golden rule, the hero’s journey, the dragon, sacrifice. As our continual ability to tell new stories, film new films, write new novels testifies, we are able to interpret the world in significant new ways.

New stories always emerge that can call into question stereotypes like the heroic individual being primary. This belief, in particular, informs his conviction that collectivism is bad, despite, for example, the fact that many of the unprecedented improvements in things like public health, sewers, vaccinations, and technology, throughout history have been social rather individual efforts.

It’s why he comes down – ideologically – on the side of order, conservatism, Christianity – because the timeless truths are, again, limited, they can be seen in lobsters, in biology, in hierarchies of competence.

Because, as he writes, ‘there is little evidence that any of us have the genius to create ourselves ex nihilo—from nothing’.

Ideology – as we saw through our definitions – has never been defined by its ability to create something from nothing, but progressive ideologies – and let’s face it, this is what Peterson is primarily criticising here in the current context – do want to change what’s not working.

So let’s return to Peterson’s initial charges and explore why we need ideology.

First, the charge that it’s utopian.

I agree, anyone that thinks a rigid implantation of a Marxist revolution, or a retreat to a feminist island will solve all of society’s problems is misguided. Does anyone really think this? Who cares? The point is that academic Marxists, postmodernists, anarchists, you name it, don’t argue this.

But this doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have some set of ideas about how to make the world a better place.

Which brings us to the second charge. Is this dogmatic? Well, actually, I think Peterson has a point here. Moral rigidity and dogmatic thinking is foolish, to say the least. Intellectual humility and openness are, I think, integral. But within any set of ideas like ‘postmodernism’, for example, there are a wide-range of positions that are so diverse they can barely be categorised together.

Remember, the definition of dogmatic is ‘inclined to lay down principles as undeniably true’, and Peterson makes claims that his Mythic Conservatism is based on ‘something like a natural ethic’ that’s ‘universal’ and ‘manifest biologically’.

As for ideologues being motivated by resentment, it seems like a suspiciously dogmatic a priori claim to make. Where’s the evidence? It’s perfectly possible to be motivated by ego and empathy, selfishness and virtue, simultaneously. When I give change to a homeless person am I motivated by resentment of the rich? It’s a baseless, odd and cynical assumption that seems at odds with the Christian message Peterson finds so much wisdom in. Rather than the more obvious motivation that some people find it difficult to see others in pain and want to help.

It could also quite easily be applied to Peterson: why is it not the same to dismiss him as simply resentful of the powerful leftist postmodern academics who have overrun the institutions he’s spent his life at?

Finally, what about the claim that ideology is simplistic and too low-resolution? Well, I think this actually tells us a lot about what ideology is and why we need it. I would argue that some ideological language is often used as a simplistic outline, a communicative device, or a basic categorisation that’s used to organise ideas, action, and communication.

Peterson writes, ‘It is impossible to fight patriarchy, reduce oppression, promote equality, transform capitalism, save the environment, eliminate competitiveness, reduce government, or to run every organization like a business. Such concepts are simply too low-resolution’…. ‘The necessary detail is simply not there’.

But what does this mean? How is it impossible to ‘reduce oppression,’ or ‘reduce government’ for example? This is simply demonstrably false throughout history. Instead, we might think of simple low-resolution values like the idea of ‘reducing oppression’ as quick shorthand to organise more complicated beliefs and ideas.

In this way ideology functions like words like ‘house’. It’s a simple loose shorthand that omits more complex details like location, contents, residents, the quantity of bedrooms, the colour of the wallpaper. It doesn’t mean the details aren’t important too. It depends on the context.

It’s necessary to categorise, simplify and communicate ideas in simplified ways that omit differences while retaining common features. For example, two feminists might agree on broad goals while disagreeing on specific details. This goes for anarchists, Marxists, postmodernists, and Jungians.

Some difference and nuance must be emptied out to conceptualise value systems broad enough to sustain organisation. The Republican or Conservative parties have many factions under a broader umbrella, for example.

This doesn’t mean there aren’t more levels of complexity and detail within. I, for example, draw from many ideologies depending on the context or the task at hand – many parts of each I agree with and many I don’t.

Not to mention this is a criticism that, again, could be applied to Peterson’s own thinking. The idea that everything can be explained by ‘running it through a Marxist algorithm’ is a strange attack to make for someone who seems to run a lot through a Jungian algorithm. In fact, all of the things he says make ‘faux-theorists’ and ‘pseudo-intellectuals’ are justified by reasons that could be applied to his Mythic Conservatism.

As Peterson himself says, ‘Without clear, well-defined, and noncontradictory goals, the sense of positive engagement that makes life worthwhile is very difficult to obtain. Clear goals limit and simplify the world’.

Finally, renouncing ideology is simply ahistorical.

Take America’s Founding Fathers. They were influenced by John Locke and the ideology of natural rights theory that was developed in the 17th century. They had their disagreements, but they were united enough on a few central principles to bring their ideological beliefs into fruition. And their ideology is something Peterson seems to identify with.

It’s impossible to make sense of any popular movements, in fact – the diggers, the levellers, Calvinists, the sans-culottes, civil rights activists, suffragettes, republicanism, nationalism, Kemalism – without recourse to the idea of ideology.

Which leads me to my final point.

Ideology seems so common throughout history, coming up time and time again, across the globe, that it might be understood, not be me, but by some, as archetypal.

Sources

Joel Fienberg and Russ Shafer-Landau, Reason and Responsibility, Readings in Some Basic Problems of Philosophy

Michael McKenna, Power, Social Inequities, and the Conversational Theory of Moral Responsibility

Catriona Mackenzie, Moral Responsibility and the Social Dynamics of Power and Oppression

Manuel R . Vargas, The Social Constitution of Agency and Responsibility: Oppression, Politics, and Moral Ecology

Moral Responsibility (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

Jordan Peterson, 12 Rules for Life

Jordan Peterson, Beyond Order

Michael Katz, The Undeserving Poor: America’s Enduring Confrontation with Poverty

John Gerring, Ideology: A Definitional Analysis

0 responses to “Why Jordan Peterson is Wrong About Ideology”

order acyclovir 400mg pill – allopurinol 300mg over the counter oral crestor 10mg