The end of the nineteenth century was a period of unprecedented upheaval. Factories sprouted in masses, railways were laid at great length, urbanisation sprawled and beckoned, and the masses were organised capitalistically and politically.

All of this happened at dizzying speed. This was the moment the modern world crashed together and dragged people from the fields to the factory floor.

Within a generation, the entire consciousness of life had changed.

Science challenged deeply-held views of the world.

Darwin published On the Origins of Species in 1859.

He pulled the Gods down from the sky and transformed humans into just another animal.

This, of course, was shocking, traumatising, existentially threatening.

The philosopher Soren Kierkegaard wrote in 1844 that, ‘Deep within every human being there still lives the anxiety over the possibility of being alone in the world, forgotten by God, overlooked by the millions and millions in this enormous household’.

Nietzsche, famously proclaiming the death of God, argued that men would become nihilistic, lose their grounding, forsake their morals, if a new ethics of man did not come.

Darwin, the death of God, the prosperity of industry, science, all pointed towards something that could be terrifying: freedom.

Kierkegaard went on: ‘Anxiety may be compared with dizziness. He whose eye happens to look down into the yawning abyss becomes dizzy. But what is the reason for this? It is just as much in his own eyes as in the abyss . . . Hence, anxiety is the dizziness of freedom’.

Freedom was the expansion of options – of ways to live life personally, of political options, with commercial options.

Warfare was changing: swords and rifles, of which there were only a few, were being replaced by stuttering guns and spat bullets at an incomprehensible rate, artillery and bombs that sent shrapnel shredding in a cacophony of unbearable noise.

The word ‘panic’ was used for the first time in 1879 by the psychiatrist Henry Maudsley to describe extreme agitation, trembling, and terror.

People were nervous, literally – a new diagnosis became popular amongst America’s elites: neurasthenia.

It was a contemporary form of stress, characterised by symptoms like fatigue, headache, and irritability.

Neurasthenia, according to physician Charles Beard, was the result of a depletion of nervous energy, but was becoming more common as a reaction to the anxieties of the modern world and of the demands of American exceptionalism. Neurasthenia was almost a fashion. Adverts appeared selling ‘nerve tonics’, self help books dominated the shelves, even breakfast cereals claimed to be able to cure ‘americanitus’.

Beard argued that there were five main causes of neurasthenia: steam power, the periodical press, the telegraph, the sciences, and the mental activity of women.

He argued that these phenomena contributed to the competitiveness and speed of the modern world.

Even time itself was to blame.

He wrote, ‘the perfection of clocks and the invention of watches have something to do with modern nervousness, since they compel us to be on time, and excite the habit of looking to see the exact moment, so as not to be late for trains or appointments. Before the general use of these instruments of precision in time, there was a wider margin for all appointments. We are under constant strain, mostly unconscious, often times in sleeping as well as in waking hours, to get somewhere or do something at some definite moment’.

The recently laid telegraphs also meant that prices and information could be sent around the world at a moment’s notice, piling the pressure on merchants to keep up with the latest news from all around the world.

According to the pre-psychological way of understanding the human mind, all of these phenomena hit the nerve endings, draining the life force.

Unnatural modern noises did this too.

Beard wrote: ‘Nature – the moans and road of the wind, the rustling and trembling of the leaves, and swaying of the branches, the roar of the sea and of waterfalls, he singing of birds, and even the cries of some wild animals – are mostly rhythmical to a greater or less degree, and always varying if not intermittent’.

As with Kierkegaard’s anxieties over freedom, for Beard, politics and religion also added to the drain: ‘The experiment attempted on this continent of making every man, every child, and every woman an expert in politics and theology is one of the costliest of experiments with living human beings’.

‘A factor in producing American nervousness is, beyond dispute, the liberty allowed, and the stimulus given, to Americans to rise out of the possibilities in which they were born’.

Excitement and disappointment were a drain on nerve-force.

But one innovation was so emblematic of the shock of modernity, of the distortion of time, of the inability of man to adapt to his surroundings, that it’s mentioned almost everywhere the topic is discussed:

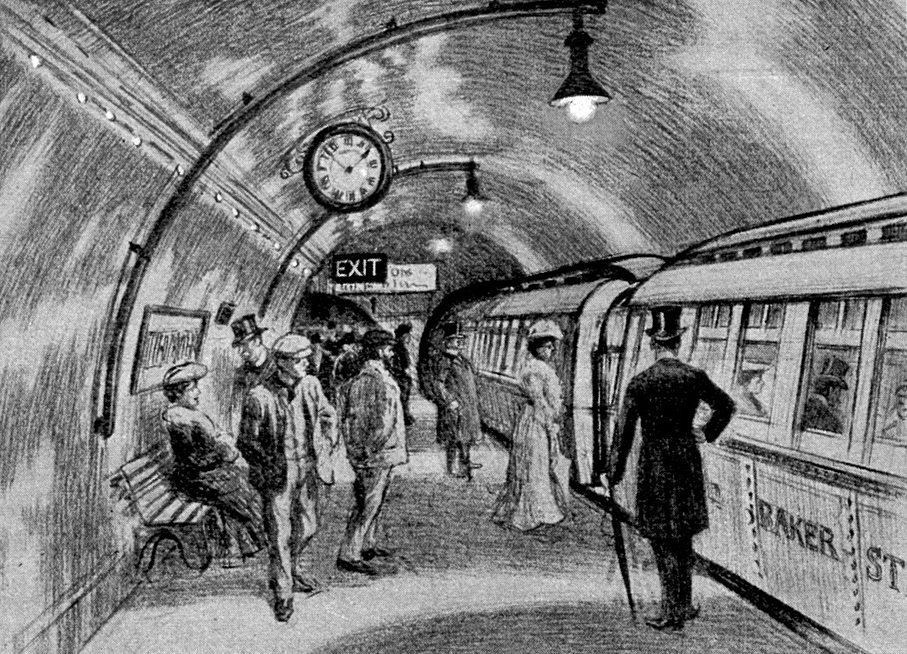

The railway.

Historian Wolfgang Schivelbusch argues that the railways didn’t just change travel, but changed the very notion of time itself.

Before the railways, cities, towns, and villages had local times, which had to be standardised for train timetables. ‘London time ran four minutes ahead of time in Reading, seven minutes and thirty seconds ahead of Cirencester time, fourteen minutes ahead of Bridgwater time’. People could imagine being in other places much more easily, changing the very way they think.

It was such a part of the cultural zeitgeist of the time that on the third of October 1868, Illustrated London News reported that five theatres were all performing the same incident: someone tied to or unconscious on a track while a train came hurtling towards them.

These productions made use of modern special effects using lights and smoke, and The Times described them as a ‘perfect fever of excitement’.

The theatres performing these spectacles were open to people outside of the centre of London for the first time, who could travel in on the omnibuses or trains. The same transport they were about to be thrilled by their fear of.

Railway accidents were common. One in 1868 killed 33 people.

One passenger wrote, ‘We were startled by a collision and a shock. [. . .] I immediately jumped out of the carriage, when a fearful sight met my view. Already the three passenger carriages in front of ours, the vans and the engine were enveloped in dense sheets of flame and smoke, rising fully 20 feet. [. ..] [I] t was the work of an instant. No words can convey the instantaneous nature of the explosion and conflagration. I had actually got out almost before the shock of the collision was over, and this was the spectacle which already presented itself. Not a sound, not a scream, not a struggle to escape, or a movement of any sort was apparent in the doomed carriages. It was as though an electric flash had at once paralysed and stricken every one of their occupants. So complete was the absence of any presence of living or struggling life in them that it was imagined that the burning carriages were destitute of passenger’.

This idea of instantaneous death mixed with machinery was so new and so shocking, that it dominated the culture.

Charles Dickens himself was involved in a train crash and wrote the ghost story The Signal Man afterwards. According to his children, he was never the same again.

All of this – industry, commercialism, fear, anxiety, thrill, trains – culminated in an emphasis on sensation and the birth of sensationalism. The point was the senses. The modern world could trigger them, play on them, manipulate them, and sell to them, all at a tremendous speed.

The Irish playwright Dion Boucicault made sensation the centre of his plays. He intended to ‘electrify’ the audience.

A review of one of his plays illustrates this emphasis on the senses: ‘The house is gradually enveloped in fire [and] [. ..] bells of engines are heard. Enter a crowd of persons. [. . .] Badger [.. .] seizes a bar of iron, dashes in the ground-floor window, the interior is seen in flames. [. . .] Badger leaps in and disappears. Shouts from the mob. [. . .] [T]he shutters of the garret fall and reveal Badger in the upper floor. [. . .] Badger disappears as if falling with the inside of the building. The shutters of the window fall away, and the inside of the house is seen, gutted by the fire; a cry of horror is uttered by the mob. Badger drags himself from the ruins’.

Drama of such speed and excitement had rarely been seen before.

In the early 1860s, sensation novels suddenly became popular.

In 1866, an article in the Westminster Gazette lamented that all minor novelists were now sensationalists.

Literary critic D. A. Miller describes it like this: ‘The genre offers us one of the first instances of modern literature to address itself primarily to the sympathetic nervous system, where it grounds its characteristic adrenaline effects: accelerated heart rate and respiration, increased blood pressure, the pallor resulting from vasoconstriction, and so on.” H.L. Mansel wrote that ‘There are novels of the warming-pan type, and others of the galvanic battery type-some which gently stimulate a particular feeling, and others which carry the whole nervous system by steam’.

So, what was lost in these tumultuous years? I think Charles Beard and Kierkegaard, in many ways, hit it on the head. The idea of freedom, anxiety of choice, the cacophony of noise, the pressure of time all becomes demanding. A type of demand that didn’t exist in agricultural societies. Yes, life also became better, more prosperous – more options – but remembering what was lost is also important.

So, if modernity is still a shock to you then slow down, take some time, turn off your phone, stop thinking. Relax.

Sources

Allan V. Horwitz, Anxiety: A Short History

Nicholas Daly, Blood on the Tracks: Sensation Drama, the Railway, and the Dark Face of Modernity

Beard, American Nervousness

Mark Jackson, The Age of Stress

David G. Schuster, Neurasthenic Nation: America’s Search for Health, Happiness, and Comfort, 1869-1920

Nicholas Daly, Railway Novels: Sensation Fiction and the Modernization of the Senses

0 responses to “The Shock of Modernity”

order esomeprazole 40mg pill – order topiramate 100mg sale cost imitrex 50mg