I’ve always been interested in the history of modernity – growth of industry, cities, technology, science – because through it we can define, analyse and interrogate what that’s meant for how we think and do things today – to uncover the pros and cons of our attitudes, beliefs, sensibilities, and to de-normalise what we think of as normal.

Because it’s not just the past – as James Baldwin said ‘History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us’ – it’s the totality of how you feel, your routines, what you’re doing, how you perceive people, friends, family, the world, what our cultural perspectives our – right now, and tomorrow. We use the past to answer questions about the present that guide us into the future.

But at the moment I have a different reason for thinking about modern life.

And after living in London for quite a long time now, we’re thinking of leaving. So I find myself thinking about the city with an urgency. What have I learned?

Modernity is a battleground for historians.

Some – most, in fact – would probably agree with historian Joel Mokyr when he says that material life is ‘far better today than could have been imagined by the most wild-eyed optimistic eighteenth-century philosopher’, and that most economists today ‘would regard [the industrialisation of the 19th century as an undivided blessing’.

But that phrase ‘undivided blessing’ has attracted criticism. What about social inequality, alienation, environmental degradation, pollution, stress, loneliness, the decline of traditional community and religious ties, mechanised warfare, imperialism?

Of course, science, industry, and technology have given us so much, but when factoring in the whole package, as historian Jeremy Caradonna points out, ‘It begins to look like, at best, a mixed blessing’.

That our shift to a modern world contains at least some downsides should be obvious to anyone who has been stressed by monotonous, cramped commutes, been disheartened by the sight of sludge in a once beautiful river, or had a front row view of the first nuclear bomb being dropped on Nagasaki.

This shift to modern life really began at the turn of the 1800s. And what’s useful about searching out the first critics of that shift is that they had one foot in a past that is now irretrievably lost to us, retained only faintly, a shadow of real agrarian lives who could rarely write about themselves – they left behind hints of what those lives felt like in words that contain worlds within them.

To look at what critics of modernity argued is not to idealise a simpler pre-modern life – one thing that stands out from diaries of the period is that people were often thankful for the new work in the factories and industry that were beginning to spring up, and they describe work in the field as irregular and difficult. One working class diary recalls, ‘As a miner I did very well’.

But as we know from the emergence of the internet, historical shifts bring surprises – both blessings and curses.

In the 1880s Arnold Toynbee wrote of the period 80 years before: ‘We now approach a darker period – a period as disastrous and as terrible as any through which a nation ever passed; disastrous and terrible because side by side with a great increase of wealth was seen an enormous increase of pauperism’.

These critics weren’t all doom and gloom – they often struggled with the relationship between the benefits and problems of modernity. They weren’t just blind critics of the ‘satanic mills’, in the poet William Blake’s words.

In fact, Blake himself was critical but forward looking. He didn’t idealise the green and pleasant lands. He strangely argued that, ‘where man is not, Nature is barren’.

He went on: ‘Nature is miserably cruel, wasteful, purposeless, chaotic, and half dead. It has no intelligence, no kindness, no love and no innocence’.

How can Blake say this when he is also known as one of our most fervent critics of dirty and dehumanising factories?

In fact, Blake chose to never leave London – he was buried here in 1827 in an unmarked grave – and until his death he believed London could become a new Jerusalem – a heaven on earth.

He said: ‘I will not cease from Mental Fight I Nor shall sword sleep in my hand I Till we have built Jerusalem, I In England’s green and pleasant land’.

I think this makes Blake a unique critic – set apart from many other thinkers of the period – but before we return to Blake’s solution, let’s look at what others were saying about the emerging modern life.

Marx’s long-time collaborator, Fredrich Engels, was sent by his father from Germany to manage a factory in Manchester, and complained of how badly industrial towns were built – the ‘foul courts, lanes, and back alleys, reeking of coal smoke, and especially dingy from the originally bright and red brick, turned black with time’.

He wrote about how the foul-smelling stream was full of debris, coal-black, with blackish-green slime pools and the bubble of gas producing an unendurable stench.

John Stuart Mill, while applauding the progress of industry, also said that: ‘I confess I am not charmed with the ideal of life held out by those who think that the normal state of human beings is that of struggling to get on; that the trampling, crushing, elbowing, and treading on each other’s heels, which form the existing type of social life, are the most desirable lot of human kind’.

But both were criticising industry that was beginning to look like this, around the middle of the century. About fifty years before, others were beginning to notice and comment on the signs of what was to come.

The smoggy coal and steam powered factories that we associate with the industrial revolution hadn’t quite gone up, but signs of the new way of life were developing – new inventions, more watches and clocks, new methods of managing the mines, basic steam engines, the spinning jenny and the use of water mills to spin yarn, canals were being dug. These new technologies of enlightenment, it seemed to their critics, were changing people’s psychologies.

People, many noted, were beginning to look at the world and relationships not as sacred, not as ideals or guides, not as valuable in themselves or for reasons unseen, but primarily in terms of usefulness – enlightenment philosophers and mathematicians like Francis Hutchinson and Daniel Bernoulli believed that usefulness could be, in Hutchinson’s word, ‘computed’.

The German novelist, philosopher and poet Fredrich Schiller said that, ‘Utility is the great idol of the age, to which all powers are in thrall and to which all talent must pay homage. Weighed in this crude balance, the insubstantial merits of Art scarce tip the scale, and, bereft of all encouragement, she shuns the noisy market-place of our century’.

Art shuns the noisy marketplace of our century – in other words, real art, mysterious art, something beyond mere use cannot keep up, is pushed out, and its returns aren’t deemed useful enough.

The poet and novelist Ludwig Tieck wondered what utility even meant. Is everything just about food, drink, clothing, running better ships and building better machines, only to eat better?

He says that actually, ‘what is truly exalted neither can nor should be of use’.

In his novel Franz Sternbald’s Journey, Tieck’s protagonist argues that the divine is not of use, and some things aren’t for humanity’s vulgar needs. He says that utility often just means more material gains at the expense of the mind. He reminds us that the mind shouldn’t be the servant of the body. It’s why art, culture, religion – which often teaches us something deeper – should be a response to a society based on utility. Art is the pledge of our immortality, he says.

Novalis said that modernity converted, ‘the infinite, creative music of the universe into the uniform clattering of a monstrous mill’.

And Ernst Hoffman wrote a novel in which the science and industry of the enlightenment was brought to a small country that was a splendid garden full of fairies. Then ‘the forests are being cleared, the river made navigable, potatoes planted, the village schools improved… roads laid down and cowpox inoculated’.

But the fairies couldn’t be converted into useful citizens because ‘they practice a dangerous trade in the miraculous, nor do they shy away from spreading, under the name of poetry, a secret poison that renders people completely unfit for service in the Enlightenment’.

What was emerging, many thinkers thought, was a one-dimensional existence that prioritised the pursuit of usefulness and commerce over all else. But this leads to a question: what was it that was being excluded and why?

When the poet Wordsworth said that, ‘The world is too much with us; late and soon, / Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers’, he was saying that some part of our potential was being wasted.

Dickens was getting at this too when he began his novel Hard Times by complaining that Victorian England’s schooling was about ‘facts, facts, facts’, at the expense of all else.

Shelley also said that real art was being ‘concealed by the accumulation of facts and calculating processes’.

Here was the point: something about art and nature shouldn’t be reduced to utility. But why?

The German Romantics complained that the new style of architecture taking over Europe was supplanting architectural styles to the point that everywhere looked the same.

They toured and loved the old medieval towns and cities. They got lost in the alleyways and admired the crooked buildings. Is this why we love to go to those old European towns with narrow labyrinths alleys – the feeling of getting lost, or stumbling upon a view, a bar, a musician, a quirky building?

What all of this has in common is that doing everything by utility means going in a straight line, building on a grid, forgetting something that makes us human: play.

What seemed to them to be being sacrificed at the alter of modernity were poetry, art, spirituality, community, tradition, and something that’s the opposite of utility – uselessness. Play, whimsy, randomness, creative experimentation with no point, sitting around and daydreaming. Schiller believed that play was what art was about.

Ludwig Tieck said that ‘the straight line, because it is always the shortest distance between two points, because it is sharp and definite, seemed to me to express requirement, the primary prosaic fundament of life’. Crooked lines represent ‘inexhaustibility of play, of adornment, of tender love’.

What’s ironic is that these things aren’t anti-utility – the utility of being creative might just take longer to develop, its dividends longer to appreciate, its harvest longer to reap.

Anticipating Nietzsche some decades later, Novalis said where there are no gods, ghosts rule. Sacrificing these importance things would leave a gap in people, a longing, an illness, waiting for something monstrous to speak to it, waiting for someone to take advantage of it.

People, they thought, felt alienated – the pursuit of money pushed out all other needs.

Shelley said that, ‘Commerce has set the mark of selfishness, The signet of its all-enslaving power Upon a shining ore, and called it gold’.

In the Mask of Anarchy he argued that:

For the tyrants’ use to dwell:

So that ye for them are made,

Loom, and plough, and sword, and spade;

With or without your own will, bent

To their defence and nourishment.

’Tis to be a slave in soul,

And to hold no strong control

Over your own wills, but be

All that others make of ye.

At the same time, these thinkers noticed that the world was becoming overstimulating, moving faster and changing quicker. Wordsworth noted that ‘a multitude of causes, unknown to former times, are now acting with a combined force to blunt the discriminating powers of the mind, and, unfitting it for all voluntary exertion, to reduce it to a state of almost savage torpor’.

Torpor meant lethargy – again, he was pointing to this idea that keeping up with being productive – in the factory or city – and being surrounded by new demands, blunted – in his words – a part of the mind.

These thinkers believed – and its interesting that there are now lots of studies that prove this – that the city, factories, being indoors too much, living with excessive noise, overstimulates and deprives us of a more harmonious state that we get from being in nature.

Novalis complained that, ‘the restless tumult of distracting social occasions’ leaves no time for ‘quietly gathering [one’s] thoughts or for the attentive contemplation of the inner world’.

This was not to say that they all believed that the natural world was Eden – as we’ve seen Blake was critical, and no-one was denying that nature could be harsh, dangerous and cruel. But as Keats said, ‘Oh ye! who have your eye-balls vexed and tired, Feast them upon the wideness of the Sea’.

This combination of a one-dimensional focus on utility and the speed of sensations and stimulation and change led to one metaphor being used again and again, in multiple countries – the great wheel of modernity.

The wheel is the perfect symbol of modern life – the new spinning jenny, the cogs of factories, the wheels of trains and later cars, the spinning of the newly abundant clocks and pocket watches – and it’s a useful metaphor because it contains so much – endlessness, infinity, flow, the spinning of growth, the continuous line of improvement. The circle is both perfect and monotonous at the same time.

Blake said that:

Endless their labour, with bitter food. void of sleep,

Tho hungry they labour: they rouze themselves anxious

Hour after hour labouring at the whirling Wheel

Many Wheels & as many lovely Daughters sit weeping

Anticipating Marx, Fredrich Schiller wrote that modern life meant that, ‘chained to a single little fragment of the Whole, man himself develops into nothing but a fragment; everlastingly in his ear the monotonous sound of the wheel that he turns, he never develops the harmony of his being, and instead of putting the stamp of humanity upon his own nature, he becomes nothing more than the imprint of his occupation or of his specialized knowledge’.

In Germany, the Romantic Wilhelm Wackenroder pointed to the ‘ceaseless turn of the eternal wheel, the uniform whirring on of time to an unvarying tempo…gearwork in which they themselves were enmeshed and pulled forward’.

Eichendorff wrote that the great cities had ‘caught the old, powerful stream in the gears of their machines simply to make it flow faster and faster. There in its dried-out bed, the wretched life of factories spreads its haughty carpets, whose reverse side is nothing but ugly, bare, colorless patches’.

If Eichendorff had lived to see the extent of industrialisation, climate change, deforestation, and the like, he would have been dismayed to have been proven right.

He said that man had ‘gone ahead and set the world up for himself as a mechanical, self-running clock’.

For Novalis nature itself had been ‘demoted to the level of dull machinery’.

What they all had in common was that they were beginning to anticipate the idea that industrialisation wasn’t just about the external world, but about what it was doing to our psychologies – the mechanisation of the human soil.

This being taken along like a wheel or a clock, endlessly spinning, predictably, some external ideal of mathematical utility the ultimate master of man has another side – of being managed – of routines being predictable, to be a slave stood at the controls, overseeing a system devoid of life, being managed by the system itself.

In his poem on London, Blake said that he ‘wander thro’ each charter’d street, Near where the charter’d Thames does flow And mark in every face I meet Marks of weakness, marks of woe’.

He’s careful to purposefully use and repeat the word chartered.

It means that the rights to the streets and river are sold off – freedoms to use them, to be in them, are for some but not for others – and they’re chartered under the auspices of utility.

Blake goes on to describe ‘in every voice, in every ban the ‘mind-forg’d manacles’ – manacles being another word for hand cuffs – people are being trapped, managed, controlled – but not physically – mentally – moved on, told where and when they can trade, banned from begging, banned from the common land which was being enclosed and sold off. Policing was growing. Permission was required to beg and the impoverished could only do so in the parish they lived in. The 1714 Vagrancy Act began to manage people on the street: the act banned things like charitable collectors, entertainers, jugglers, minstrels, men who had abandoned their wives and children, anyone sleeping or begging, and so on.

In short, all life was to be subsumed under the great wheel of utility, or to move out of its way.

So let’s go back to why, despite it all, Blake believed in the city.

I’m at St Pauls and about a mile that way is Westminster Abbey. Both of these buildings appear multiple times in Blakes works.

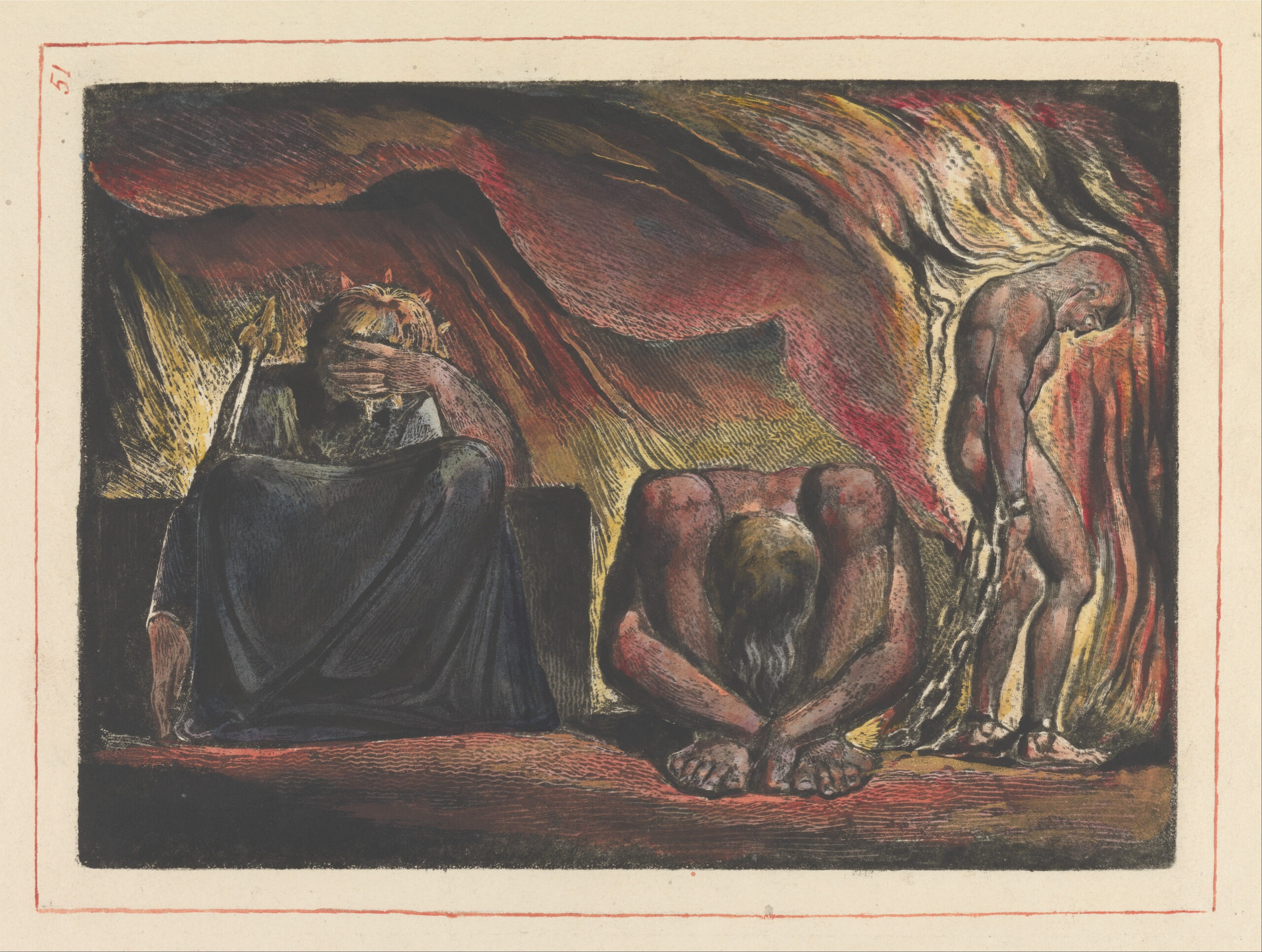

Take a look at this image from his poem Jerusalem: St Paul’s in light behind what Blake describes as Jerusalem’s naked beauty, and St Paul’s in darkness to the left behind the shadowy figure of Vala.

Blake thought that this building in its neo-classical style – geometrical, repetitive, symmetrical – was everything that was wrong with the one-dimensional mathematical thinking of the time. What was called neoclassicism. While it certainly looks impressive, many like Blake were critical of its flatness, simple pale colour, its uniformity, and the vast wealth that went into building it, surrounded by poverty.

But moving down the road, he loved Westminster Abbey – an older gothic building. Many of the Romantics idealised older architectural styles that they thought more in keeping with nature.

Inside old churches they likened the pillars to tree trunks, the architecture to overgrown forests, the asymmetry. The French romantic Francois-Rene Chateaubriand likened the experience of being in a cathedral to the sublime labyrinths of a dark forest. Cathedral architecture, he said, ‘originated in the woods’.

Unlike other Romantics, Blake places his ideas about redemption squarely in the middle of London. In this way, he’d despise how the traffic in London developed but would probably be happy with some emerging trends – solar and wind energy, low traffic neighbourhoods, city farms, prioritising parks and green areas.

In other words, nature and civilization, nature and culture, natural and artificial, shouldn’t be antithetical to one another. It’s not even that they should coexist – they should be one and the same. Synthesised. The same side of one coin even. It’s a reflection of the beautiful romantic notion that the romantic writers weren’t people, thinkers, reflecting on nature, but were nature reflecting on itself.