Individuals have rights, and there are things no person or group may do to them (without violating their rights).

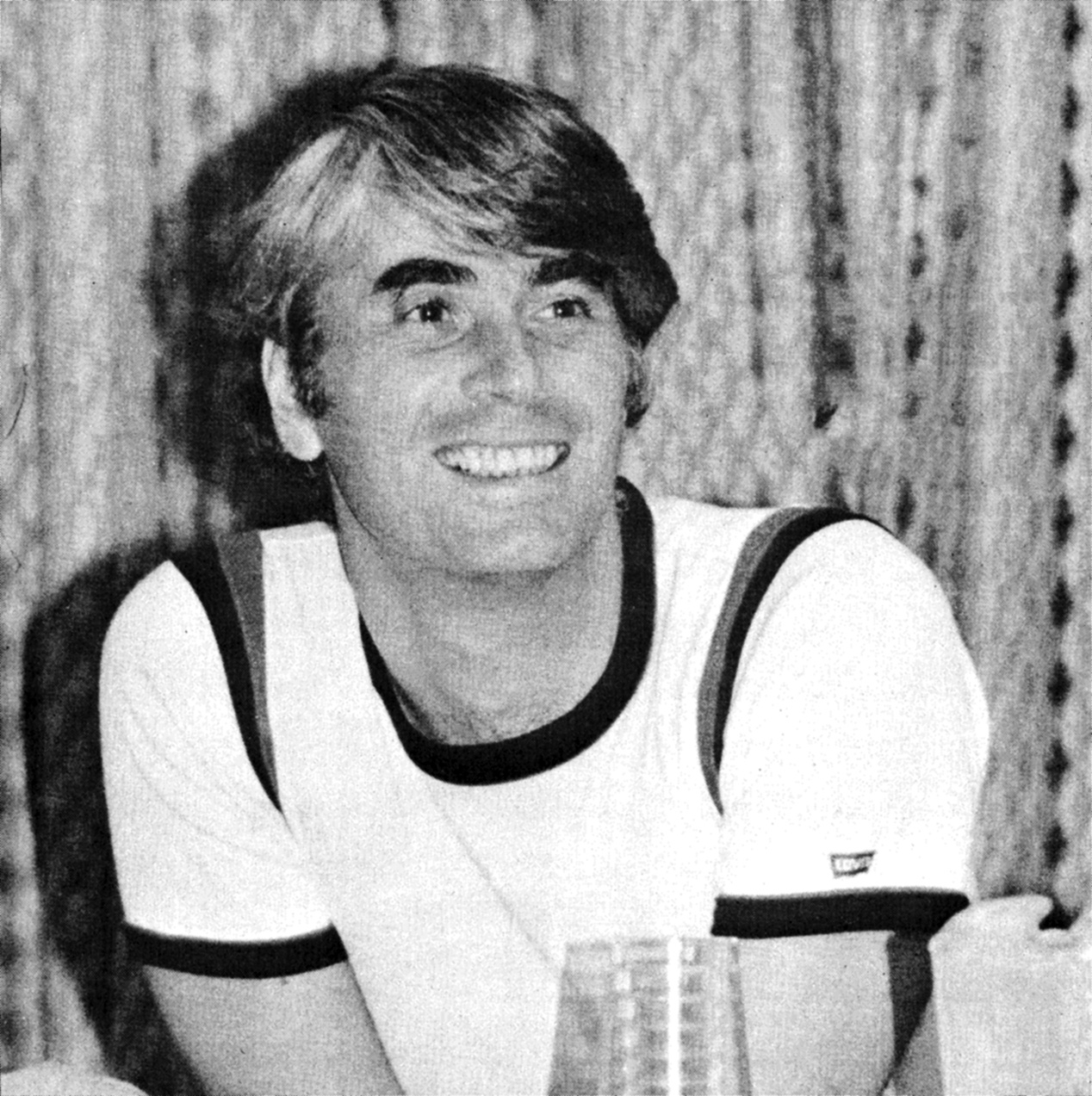

This is American philosopher Robert Nozick’s bold pronouncement at the beginning of Anarchy, State and Utopia, a 1975 book that is a largely a response to Rawl’s 1971 A Theory of Justice, which I’ve covered here.

For Nozick, the rights that individuals have are natural, of fundamental importance, and completely, universally, unequivocally inviolable.

These rights, he argues, must be respected at all costs.

They aren’t designed by institutions, or dreamed up by revolutionaries, written into contracts and protected by lawyers. They are part of being human.

This is the basis of Anarchy, State, and Utopia.

For Nozick, there is only the individual.

There might also be such a thing as the state, as society, as culture, but these phenomenon are only the product of individual humans coming together. The individual is primary.

In this, Nozick follows the 17th century English philosopher John Locke, who argued that individuals have natural rights and that, ‘no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions’.

Infringing upon and violating these rights for the sake of others, for the benefit of society, is then immoral.

But this hints at a problem.

How could the state possibly be justified?

Taxation, the rule of law, a system that forces its citizens to pay for roads, schools and hospitals, is surely a violation of an individual’s natural rights as a human to be free to make their own choices.

‘Boundary crossing’, as Nozick calls it, crossing the line and infringing upon a person’s freedom, is surely only permissible with consent.

This, loosely, is the position of the anarchist.

The anarchist argues that because of the inviolability of individuals, no state can be justified.

For Nozick this is the fundamental question of political philosophy: whether there should be any state at all.

He wants to justify what he calls a minimal state. One that simply protects an individual’s right to freedom, and nothing else. He wants to argue that this is both justified philosophically, and could develop from a state of nature historically.

Against Rawls’ redistributive state, he also wants to argue that this is where it would stop, with any further redistribution of wealth being a violation of natural morality.

The question is how, if it is morally impermissible to violate individual rights, would a state still develop over time with ‘no morally impermissible steps’?

Imagine a state of nature.

The state of nature has no state, no political institutions, no culture, just pre-state humans living ‘naturally’.

As we’ve seen, in Nozick’s state of nature, individuals have ‘natural’ rights.

He borrows this argument from Locke and, briefly, it looks something like this: Individuals are born with their own lives, their own faculties, their own choices, and thrown into a world which must be made use of. If an individual plucks an apple from a tree in a state of nature to eat, by mixing his labour with it they make that apple their property, all of which arises out of man and the earths nature. This, in brief, is natural rights theory.

If someone violates these rights, by harming another, for example, or stealing from them, they’ve violated the law of nature.

So how would these violations be dealt with in a state of nature? How would troublemakers be dealt with?

People would, of course, defend themselves, or they’d band together in defence of each other. But some would be too weak and secure, by exchange, protection from the stronger.

In short, ‘in union there is strength’.

Nozick argues that protection agencies would develop, security firms, mutual protection cooperatives, et cetera.

Within these agencies, certain mechanisms would develop to resolve disputes without leading to violence. Norms and procedures would develop, courts and codes.

You’d have, ultimately, a free market of competing and varied security and dispute companies.

But what would happen when two agencies come to different decisions in a dispute?

In some cases, this would lead to bitter disputes, and in some, to violence.

Nozick notes that the larger an agency is, the more able it would be at protecting its clients. The more successful agencies would attract more clients. Disputes would be resolved internally without resorting to violence. Costs would decrease. The geographic area being protected would both increase in size and become more safe. Some agencies would simply be better are protecting their clients than others. Slowly a monopoly of kinds would develop in an area.

Nozick writes that, ‘Out of anarchy, pressed by spontaneous groupings, mutual-protection associations, division of labor, market pressures, economies of scale, and rational self-interest there arises something very much resembling a minimal state or a group of geographically distinct minimal states’.

This idea of a natural historic development he calls an ‘invisible-hand explanation’ for the emergence of society.

Max Weber famously defined a state as a community that has a monopoly on force in a given geographic area.

At this point Nozick has outlined a kind of anarcho-capitalist society.

But he argues a state would continue to naturally develop.

At this point, though, Nozick says: ‘There are at least two ways in which the scheme of private protective associations might be thought to differ from a minimal state, might fail to satisfy a minimal conception of a state: (1) it appears to allow some people to enforce their own rights, and (2) it appears not to protect all individuals within its domain’.

In other words, a person might take the law into their own hands without violating the law of nature. Setting up their own protection agencies or arguing they have the right to enforce the law of nature themselves. Others would opt out of paying for security completely.

A state, of course, would not allow this.

Nozick’s justification for a state arising is centred around risk and fear.

Consider threats.

Nozick argues that if someone was threatening to either murder or harm someone, or take their personal belongings by force, the protection agencies would have the right to step in without violating that individual’s rights.

He argues that lone rights enforcers, a kind of wild west gunslinger, or an unreliable or mentally impaired interpreter of the natural law, would be a risk to the safety of others, and that the dominant protection agency would have a veto on whether their claim to be able to practice independent law was justified or not.

Nozick writes: ‘an independent might be prohibited from privately exacting justice because his procedure is known to be too risky and dangerous’.

The dominant protection agency may judge the right of any procedure being applied to its client and punish anyone who judges their client unfairly.

It might, for example, publish a list of procedures, codes, practices, laws it deems fair and reliable.

This leads to a monopoly over the right to practice the law. The dominant agency becomes the final arbiter of rights and justice in the geographic area.

This is a de facto monopoly on violence.

The minimal state.

Nozick argues that this is the only philosophically just state. Any further move into taxation or redistribution is a violation of those individual natural rights, a state coercing citizens by taking their property.

He argues that philosophers like Rawls, or proponents of the welfare state, for example, have a conception of justice that is ‘patterned’, and that enforcing the pattern leads to coercion.

The only just distribution is one where property – or holdings – have been passed from person to person voluntarily, without coercion, without a violation of rights.

He calls this a ‘theory of justice in holdings’.

He writes that, ‘the general outlines of the theory of justice in holdings are that the holdings of a person are just if he is entitled to them by the principles of justice in acquisition and transfer’.

He continues: ‘If each person’s holdings are just, then the total set (distribution) of holdings is just’.

As long as the holding is acquired fairly, and that transfers between people are consented to and voluntary, then the resulting pattern is, by virtue of natural rights law, just.

In contradistinction to this, any attempt to redistribute according to a pattern like ‘from each according to his ____, to each according to his ____’ is a violation of liberty, of people’s right to choose, and to the just transfer of property over time.

Nozick illustrates his argument about patterns being unrealisable with his Wilt Chamberlain example.

He asks us to imagine a society in which justice is meant to be achieved by a pattern, like Rawl’s difference principle. The pattern is achieved through redistribution.

In this society the famous basketball player Wilt Chamberlain charges 25 cents to his fans to watch him play.

Over the season, he earns $250,000.

This is so much more than anyone else in the society that it disrupts the just pattern.

But all of the fans have freely, of their liberty, given Chamberlain their 25 cents. So how can the new distribution not also be just?

Nozick’s answer to Rawls is the most influential articulation of libertarian theory developed in the 20th century.

But there is plenty of room for criticism.

Both Rawls and Nozick provide little justification for their foundations. The choice between the contractarian position of Rawls and the natural rights position of Nozick are based on intuition, leaving both open to criticism.

Anarcho-capitalist Murray Rothbard has also criticised Nozick by asking, if his theory is true, why has no such state developed naturally and historically? He should, he argues, advocate for anarchism and wait for his ‘minimal state’ to develop.

I’ll return to criticisms and a critique of Nozick in a later episode, but it is undeniable that he provides a unique challenge to many areas of political thought.

As David Boaz has written, Nozick ‘defined the ‘hard-core’ version of modern libertarianism, which essentially restated Spencer‘s law of equal freedom: Individuals have the right to do whatever they want to do, so long as they respect the equal rights of others’.

0 responses to “Robert Nozick: Anarchy, State & Utopia”

buy generic valtrex 1000mg – buy proscar online buy forcan no prescription