‘This above all: to thine own self be true’

I want you to close your eyes. Focus on how things enter your mind. Where are you? Notice the sounds around you as they appear in your consciousness. Concentrate on my voice, on how it’s guiding you to do something. Now direct your attention to whatever sensations you can feel – the feeling of the chair you might be sat on, your feet on the floor. Focus on your emotions: you might be happy, sad, tired, energetic. All of these things are like objects to concentrate on. They’re almost separate from your consciousness, as if your conscious focus selects them, shines a light over them, like a torch. Now return to focus on my voice – it has entered your head, motivated you, prompted you, driven you to do certain things.

Now say the first thing that comes into your head. Was that really you? Where did that word come from? A memory, an idea, a conversation. Is anything really originally you? How about this: focus on how you feel – you might be sad, happy, angry, tired. But again, don’t you feel like your conscious you is separate from these things; that you’re overcome by them, involuntarily. Doesn’t it feel like we’re all tugged, pushed, and pulled around? Are we really free?

Okay, open your eyes. What can we find that is really ours? Authenticity might be thought of as ownership or self-possession. Today, we’re going to take a short historical and philosophical tour of the inner you.

Today, ostensibly, we’re free. Free to do what makes us happy, to be anything we strive to be, to choose our own paths. We even feel free from parts of ourselves – that our emotions are something separate from us, that there’s a real us beneath them, a supra-inner rational core that transcends everything outside of it, that is somehow higher than fleeting emotions that make us do things that aren’t really us.

We might think of an onion. The outer layer is the outside world, then we have emotions, beliefs, our bodies. Then we have our thoughts, our consciousness interacting with all of that. And then? Unconscious desires? What’s at the centre? Is there a centre?

The history of the search for authenticity has sought to understand this onion. It has been approached in many ways. Sometimes as a revolt against the outer layer, against standards given to us by society. Other times as taking off a mask. Or rejecting reading a script someone else has written for us, whether god or the bible or society and its rules.

Philosopher Jacob Golomb writes that, ‘the concept of authenticity is a protest against the blind, mechanical acceptance of an externally imposed code of values’.

The idea of an original self, a primordial condition, a personal or truthful way of living has been a persistent – maybe universal – feature of human history. Christianity’s original sin, fall from the Garden of Eden, the idea of utopia or paradise are all searches for a type of authenticity. And today, the idea that there is a true self behind the curtain, outside the matrix, or to be found on a backpacking trip is a powerful, maybe central modern idea.

But around 200 years ago, a monumental paradigm shift occurred. For millennia, it was believed that the cosmos was ordered. Knowing oneself meant knowing one’s place in the universe. You were born to be a butcher, a king, or a slave. For the pre-moderns people had a function within a wider plan – God’s plan. So there was no sense in ‘making oneself’ or crafting a personality. Identity was bound up with the rest of universe. Modernity changed this.

The reformations and revolutions and enlightenments that marked the beginning of the modern age put the individual front and centre. And science demystified the universe, secularising Europe. If I’m not born into my place in the world, if God doesn’t define who I am, then who am I?

We all want to live organically, truthfully, want our identities to be ours.

Is it any wonder that Hamlet – the story of a young man wrestling with the question of ‘to be or not to be’ – is maybe the most famous and most retold tale of our time? Its themes – individuality, inner turmoil, right and wrong, cowardice – are universal ones.

As Polonius tells his son in Hamlet

This above all- to thine own self be true,

And it must follow, as the night the day

Thou canst not then be false to any man.

But what or where is this authentic self that we must listen to? Does it even exist? Maybe ‘follow your heart’, ‘be yourself’, and ‘listen to your gut’ are as ambiguous and meaningless as they often sound. To find out, we’ll begin with a question the great French Enlightenment philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau asked: are we all wearing masks?

Rousseau was interested in the difference between our modern society and that of the hunter-gatherers. His most important observation was that hunter-gatherers lived in face-to-face, direct, unmediated communities. Everyone knew each other, and everyone, more or less, performed similar tasks and were self-sufficient.

In modern society, however, we divide our tasks between us and each specialise our skillsets. We have a much more distinct division of labour.

This has one important consequence: we need things from each other.

Moreover, we’re constantly asked to prove that we can deliver, that we’re up to the job, that we have the required skills. Modern life is a constant job interview.

Not only this, many of us, in seeking the status required to prove we have value, will bullshit. We’ll attempt to create an image of success by exaggerating the stories we tell, putting filters on our Instagram posts, by editing what we display of our lives and embellishing the truth.

So ultimately, the competitive nature of modern life forces us to wear masks that aren’t really us.

Rousseau’s solution is a classic one: ‘Follow your heart’. Don’t edit – do what feels right. But what does that really mean?

He thought that when we embellish the truth we selectively draw upon certain facts. We omit certain details or do something because we think it will please someone.

But if we focus on our feelings rather than the facts, we might find that we were selective of certain facts because we felt a certain way – ashamed, insecure, jealous.

Rousseau wrote the first modern autobiography – Confessions – which encapsulated this idea: write confessedly, unedited, warts and all, about the things you’ve done and the feelings that motivated them. In doing this you’ll get to the truth.

He says: ‘I have only one faithful guide on which I can count: the succession of feelings that have marked the development of my being…. I may omit or transpose facts, or make mistakes in dates; but I cannot go wrong about what I have felt or about what my feelings have led me to do; and these are the chief subjects of my story’.

So we see two key concepts in Rousseau that we might find parallels with in later things: the importance of emoting, and the need to express that emotion in writing.

What we see in Rousseau is a type of expressivism; that we should take our inner experience and express it outward into the world, turn it into art, literature, into creativity. Life should be turned into a great novel.

Rousseau had a thunderous impact on European culture, on the Enlightenment, on Romanticism. Painters, novelists, philosophers all quoted Rousseau and the idea of emoting.

He was the first to psychologise the idea of alienation – that we live in chains, distanced from our true selves, dissatisfied by our work routines and social and political life. We don’t feel like us. Alienation is a common theme in the history of authenticity. Marx argued we were alienated because, among other things, we lived to produce products for others to sell, commodities that we only contribute to in pieces on the factory line. We have creative essences that need to be exercised, life is meant to require fullness, a range of activity, and a social and political life that we all contribute to.

While both Marx and Rousseau were both interested in how we were meant to live, neither of them used the term authenticity. But at around the same time, the Danish philosopher Christian Soren Kierkegaard began trying to think clearly about what it would really entail.

In his diary, the 22-year old Kierkegaard wrote that, ‘the thing is to find a truth which is true for me, to find the idea for which I can live and die’.

He argued that life’s real calling was to take leaps of faith towards what we feel is the truth, turn it inward, and live it through passion and action.

Kierkegaard agreed with Rousseau that authentic life required emotion, but he was also concerned that too much reflection, an excess of naval-gazing and a wandering mind, would kill action. To live was to do things passionately.

In The Present Age he wrote that, ‘Our age is essentially one of understanding and reflection, without passion’.

Kierkegaard knew that the truth that really matters is the one we decide to hold for ourselves, and that thinking, logic, and reason are all good enough tools to aid us in getting there, but cannot take us all the way. There are no exterior reasons that can be given to convince you to make a particular choice, to decide whether a reason given has force for you.

Deciding how to live – whether to be a parent, a schoolteacher, a liberal, a painter – required a careful study of the facts followed by a resolute and passionate leap of faith. We must dive head first into what feels right.

He calls this subjective truth.

For Kierkegaard, intention + commitment + passion = authenticity.

Moreover, a rigid dedication to science, facts, or ethics won’t produce progress; for that something must be created, creatively, from within – again passion + action.

Kierkegaard wrote that, ‘With every turning point in history there are two movements to be observed. On the one hand, the new shall come forth; on the other, the old must be displaced’.

Kierkegaard confronts us with a powerful question: why is it that we try to be rational? Why learn and read? It’s usually and ultimately, as Rousseau argued, because of our passions, our feelings, our gut.

As Hume said, ‘reason is and ought only to be the slave of the passions’.

Passion is not about certainty, it is about faith, about diving into them for good or bad, and seeing where they might lead you.

Kierkegaard and Rousseau both lived through a period of unparallel scientific and industrial advance. Many of these advances challenged the Christian framework of European life. To many, nowhere did this seem more dangerous than regarding ethical questions: standards about right and wrong.

The scientific view is built around causation. That I work because I want to eat, I eat because I’m hungry, I’m hungry because I need energy. But ethical values – be good to one’s neighbour, give to charity, show courage, be modest and frugal – were traditionally said to come from God – he commands them, encourages them, they’re written in the Bible. What would happen if we decided that they weren’t God’s will but instead were something more terrifying: human, all too human?

How do we define our values? We’re often presented with values as if they’re dogmas, standards we’re expected to live up to. I value being kind, for example.

Now it’s easy to assume that we value being kind because it’s good for our communities, for human flourishing, but that’s not always the case. Sometimes people need tough love, sometimes kindness kills, sometimes we just don’t feel like it. In those circumstances, when we irritably ask, ‘why should I be kind?’, the 19th century reply might have been: because God tells us to in the Bible.

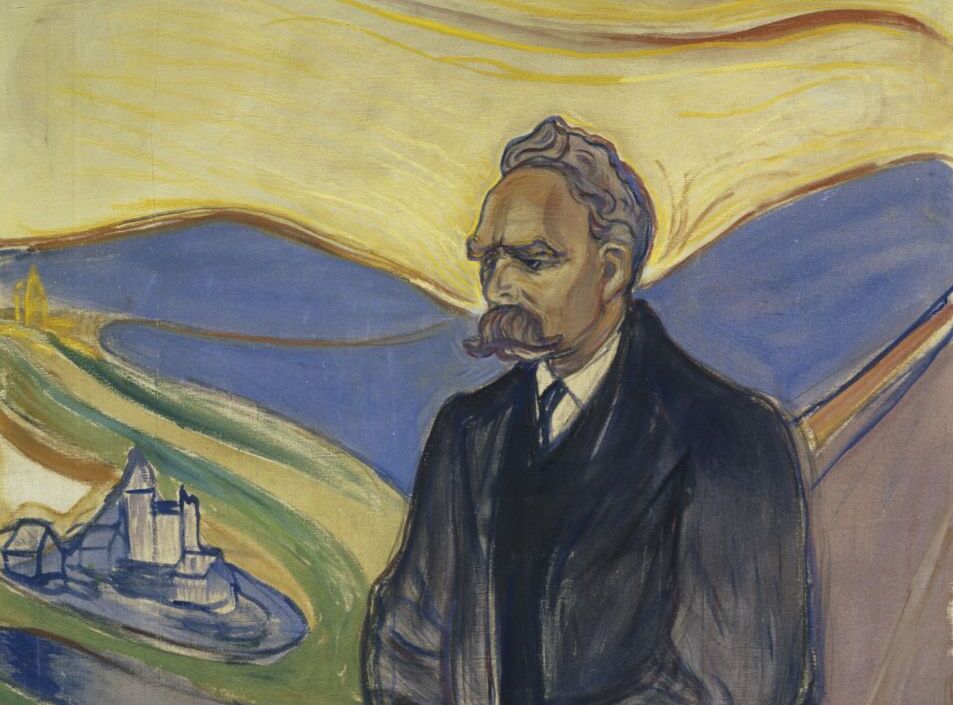

But people were increasingly questioning this view, and an unknown German philosopher, Fredrich Nietzsche, realised something powerful: if God wasn’t the source of our values, then we were.

Where would they come from, would they become, in a secular world?

Kierkegaard had already pointed to the difficulties of these kinds of questions: shall I pursue happiness? Duty? A project? A family? Which political principles?

One answer is that we find the answers out in the world, and another is that we create the answers ourselves. Nietzsche wrote that, ‘all evaluations are either original or adopted—the latter being by far the most common’.

Most people, he thought, adopted their values, beliefs, and worldviews from others. We were sheep and Christianity had encouraged this, priests literally adopting the metaphor of the shepherd and the flock.

However, the flock had forgotten their creative power. That not only could values be adopted from the shepherd, or commanded by God, but could be created by all of us.

For Nietzsche, to do this was an artistic act. It meant taking our pathos – our sentiments, emotional states, temperaments, and dispositions, and organising the chaos of a godless world into a harmonious whole.

For Nietzsche, we must ‘give style’ to our characters, progressively integrating our traits and habits and patterns into a creative force that is for us.

In this sense, our lives are like novels – we embark on projects with beginnings, middles, and ends – we think of chapters, we give ourselves and the people we encounter characteristics, and ultimately, the meaning of our life story is down to us.

Creativity is power, if we know how to use it.

For Nietzsche, the values, lessons, skills, and histories we all draw from are like ladders. We use them to climb, and it’s part of our fate to have to draw upon them. We must love our fates, acknowledge what we’re best at, know our environments, but ultimately, at the top of all the ladders, there is only us. He wrote, ‘And if you now lack all ladders, then you must know how to climb on your own head’.

‘To accomplish means to unfold something into the fullness of its essence… to lead it forth into this fullness—producere’.

Unlike Rousseau, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, who were concerned with the way society forces us to be something we’re not, for Heidegger it is our own anxiety and the prospect of our own death that elicits the desire for an authentic life.

Why is this?

For Heidegger, death is an ontological fact of life, and becoming aware of it is an awareness of our limited finitude; an acknowledgment that our lives are temporary.

Most people inauthentically avoid reflecting on this. But if we do we become acutely aware of something: in facing our own death we are forced to choose how to live.

We often put off plans like learning a language or doing charity work or travelling or painting with the excuse: ‘I’ll get to that later’, when I have time.

If our lives were infinite this would be honest – we could do anything, go anywhere, be everything. It’s only because our lives are finite that we’re forced to choose, that we have to fit a finite amount of things into it. Death forces us to confront our choices.

Now, certain things do continue on after our deaths. Children, our work – we might have written a book, taken some great family photos, created a unique cake recipe.

So authenticity involves acknowledging that we have limited time to do something lasting. It’s a relation between the finite and the infinite.

Heidegger asks to think of the average person, the statistical ‘anyone’. Socially, they cannot die because they can simply be replaced. The average baker in a town is replaced with another, fathers are replaced by sons, one employee replaced with another. But think about the way the world mourns when ‘great figures’ die. Or even when that incredible little irreplaceable bakery in town closes down.

There’s a sense that we’ve lost something unique, that their life was finite, that they’re gone and cannot be replaced.

Living authentically means making choices with this in mind – not delaying them or acting them out ‘averagely’.

This doesn’t mean you have to be a great figure or die for some noble cause. The baker can also be irreplaceable – so friendly, talented, original, creative in such a novel combination that the town would mourn their loss.

What’s unique to Heidegger is he says this psychology is within all of us, and that if we ignore it, it will result in an anxiety, and we’ll float through life haunted by an existential guilt.

So there’s a sense in which authenticity is an owning of one’s choices, but as we can see from the baker and the ‘great figure’ examples, there is something social about Heidegger’s conception of authenticity too. We are not isolated, authenticity is not just something within, because we are ‘beings-in-the-world’, and this is unavoidably ‘being-with-others’ in a social context.

Heidegger’s account of authenticity is a journey. The world is presented to us first in its averageness, its everydayness – the statistical average baker. We make idle chat, discuss the weather, we ‘fall’ into what others are saying, we’re seduced by people into becoming average. We’re tempted to go along with the world, to ‘fit’ in.

Dasein ‘compares itself with everything’, and ‘drifts along towards an alienation in which its ownmost potentiality-for-Being is hidden from it’.

But this is always accompanied by guilt and anxiety – I should be doing something, being someone. We’re always offering excuses, ‘isnt it too late?’ Confronting this – acknowledging our finite time – forces us to acknowledge that we have a unique contribution to make.

We can see some parallels with Heidegger in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Conrad saw a confrontation with extreme situations, like the prospect of death or the danger of the jungle, as a way to test of your authentic self when the support of society is ripped away:

Mr Kurtz lacked restraint in the gratification of his various lusts…. But the wilderness had found him out early, and… had whispered to him things about himself which he did not know, things of which he had no conception till he took counsel with this great solitude—and the whisper had proved irresistibly fascinating. It echoed loudly within him because he was hollow at the core.

Okay, let’s pause a moment. What do we have so far? ‘Know thyself’ or ‘to thine ownself be true’. We have taking off our masks and searching through our own emotions – something that’s turned since Rousseau into modern psychology. We have passion, action, creativity, defining our own values, confronting our own deaths, challenging ourselves.

But all of these things are still given to us, I’ve read them in books and I’m relating them to you. Our emotions and passions push and pull us around – they sometimes feel like they overcome us. Are we ever really free? Free to really choose, to become something just for ourselves?

Remember at the beginning when I suggested that your consciousness – shining a light on objects, ideas, sounds or words – is like a torch. For Jean-Paul Sartre, the 20th century existentialist, our true free selves is that torch. It’s completely free, transcendent, spontaneous, unencumbered by everything – emotion, masks, scripts written by others. For Sartre, we are always free – and that’s at the heart of authenticity.

Sartre’s difficult to summarise but I’ll try to give a brief overview. Close your eyes again.

Think of all the things we’ve covered. Think of your hobbies and passions. Think about you.

For Sartre, consciousness – like the torch – highlights these things, but it’s always separate from them. Focus on the idea you have of yourself; you are now consciousness focusing on yourself. But it’s an idea of yourself – made up of biases, observations, reflections – and your consciousness focusing on it is something different. Sartre writes, ‘The ego is not the owner of consciousness; it is the object of consciousness’.

Consciousness has no content of its own, no character traits, no personality, it flits about spontaneously focusing on this and that.

Sartre says: ‘To be is to fly out into the world… in order suddenly to burst out as consciousness-in-the-world’.

This means that no matter who you are, what your beliefs are, what society tells you to do, or what emotional state you’re in, you’re always free to do otherwise, and this freedom is authenticity.

Let’s take an example.

I’m 6 foot 2 inches tall and I’m 34 years old. I’m never going to be a professional basketball player. And it makes no sense for me to try. I’m not good at it, there are no basketball courts, I’m never going to be accepted onto a team. I might even hate basketball. These might all be absolute facts, but none of them can stop me from trying to be a professional basketball player. In this sense, its not my identity that determines what I do, but what I do that determines my identity.

We’re not born to do anything, there’s no such thing as fate, we’re not controlled by our emotions or told what to do, we always have an option: to say no. I am always free to do otherwise from what is expected of me.

That means that the transcended consciousness – the torch – cannot be defined by anything. It is just movement, just light. It is not determined by beliefs, your IQ, your sexuality. It can always escape from these things. For Sartre, ‘the past history of the world is of no use’ – I am always on my own.

Philosopher Jacob Golomb puts it like this: ‘Sartre’s characterization of consciousness as free spontaneity reflectively positing its own transcendent objects, as active rather than reactive, as neither caused by nor causing external objects and as transparent to itself, calls to mind the attributes of authenticity: spontaneity, lucidity, activity, reflectiveness, self-sufficiency and originality’.

For Sartre, the result of not using this freedom properly results in what he calls ‘bad faith’. Consciousness spontaneously darting and flitting around sees the world in lots of different ways. We see the world in a way that’s relative to our own lives, our own projects.

Take an orange. When I look at it, when I create an idea of it in my head, I might look at it because I’m hungry. I might be a chemist researching vitamin C. I might be an artist painting fruit in an 18th century scene. Or I might be making a Youtube video thinking about it in relation to authenticity.

The ways we look at and think about objects are unlimited.

But that also means we can ignore things that we shouldn’t. It means I might avoid looking properly, or look ambiguously, emphasising certain parts or ignoring others.

Take the way I look at and think about this cigar. Like the orange, there are many ways I could look at it. But I see it as a source of relief, a way to relax with a drink, a crutch maybe. I ignore its effects on my health, its costs, how other people dislike it.

This is bad faith: I’m not considering all sides. We might think of comfortable half truths or ignoring the elephant in the room. And, of course, we look at our own characters in bad faith too. Telling us convenient stories about why we can’t do this or shouldn’t do that.

Bad faith is finding comforting excuses. Authenticity means looking lucidly, freely, piercingly, with that torch, at every nook and cranny of myself and my life.

There’s a disagreement with Kierkegaard here; where Kierkegaard argues too much reflection prevents us from acting, Sartre thinks that reflection is key: as long as it’s honest.

Okay, lets return to our list. To it we can add clear, lucid, no-excuses thinking. Exploring all sides of an argument, trying to understand our biases. We’re back at know thyself. Digging down. Exploring. Finding something within that we’ve ignored. Now, this is a complicated list. How might we think about what we’ve learned from these philosophers?

It’s often said that authenticity can be equated with childhood. That in childhood we’re like Rousseau’s hunter-gatherers, unmoulded by society, free to express ourselves naturally.

In Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich, the main character realises he gradually became unhappier as he grew up.

‘It is as if I had been going downhill while I imagined I was going up. And that is really what it was. I was going up in public opinion, but to the same extent life was ebbing away from me’.

More recently, the psychoanalyst Alice Miller argues in the bestselling Drama of the Gifted Child: The Search for the Truth Self that many unhappy people didn’t receive the parental support they needed growing up. She says, ‘every child has a legitimate need to be noticed, understood, taken seriously, and respected by his mother’.

When they don’t, the child develops a ‘false self’ to please their parents, burying the feelings that were discouraged and developing traits encouraged by parents.

According to Millar, the key to overcoming this is learning to express emotions and ideas without shame and guilt. In this sense, Rousseau was right; we feel shame or guilt because we’ve been taught that something is shameful or guilty. If we tear off the mask we might ask why we care, or who we are trying to please.

Some are critical of this, though. Of the idea that there’s a true inner creative authentic pure child waiting to come out.

It supposes that there is a real ‘me’, a concrete I, buried beneath the surface. Take this 1890 description of the self from the psychologist William James: ‘Properly speaking, a man has as many social selves as there are [groups of] individuals who recognize him and carry an image of him in their mind…. He generally shows a different side of himself to each of these different groups…. We do not show ourselves to our children as to our club-companions, to our customers as to the laborers we employ, to our own masters and employers as to our intimate friends. From this there results what practically is a division of the man into several selves’.

Many like James are critical of the idea that authenticity comes from within. Authenticity is a social phenomenon as much as a psychological one. The anthropologist Clifford Geertz argued that humans are cultural animals, writing that, ‘man is, in physical terms, an incomplete, an unfinished animal;… what sets him off most graphically from non-men is less his sheer ability to learn (great as that is) than how much and what particular sorts of things he has to learn in order to function at all’.

In The Authenticity Hoax, Andrew Potter notes that, ‘We don’t find our authentic self by peeling away the shell of civilization until we reach the hard nut of the natural self at the core. The self is more like an onion; there is no “natural self” to be found at the center because there is no center’.

It’s an odd choice of metaphor, because an onion does have a centre. But we can understand roughly what he means. How is it possible to think about an authentic self when the idea is so ambiguous? Moreover, critics argue that the pursuit of authenticity is a self-centred ambition, egotistical, individualistic and self-absorbed.

Ultimately, having a theory of authenticity is impossible because that would contradict the idea of authenticity itself. Authenticity cannot have a meaning, definition, otherwise it falls into its own trap of being a ‘script written by others’, something that’s not really yours. As Nietzsche said, ‘I mistrust all systematizers and I avoid them. The will to a system is a lack of integrity’.

So where does this leave us? First, while Nietzsche distrusted systematisers he did, as we saw, encourage ‘giving style’ to our characters, integrating patterns, knowing our traits. There are similarities here with Sartre, who used the metaphor of a ‘melody’ to describe how consciousness constructs a self, and Rousseau, who advocated for expressive, confessional writing.

Most of these thinkers wrote in many different styles and mediums – philosophy, fiction, film, poetry, autobiography. So there’s, maybe, a first stage of exploration, experimentation, a tugging at seams, a lucid investigation of one’s character. Rather than being prodded, pushed, and pulled around, we can at least prod, push, and pull at our own selves, our intentions, our beliefs, our reasons for doing things.

And a second stage that they all seem to have in common is an emphasis on doing, on taking action, decisively and passionately, creating – our own stories, values, art, literature, our own worldviews.

To return to our opening statement, we might say that knowing thyself is one part of being authentic: but creating thyself, and the world, is just as important too.

Sources

W. R. Newell, Heidegger on Freedom and Community: Some Political Implications of His Early Thought

Martin Heidegger, Being and Time

Andrew Potter, The Authenticity Hoax

Charles Guignon, On Being Authentic

Maiken Umbach and Mathew Humphrey, Authenticity: The Cultural History of a Political Concept

Jacob Golomb, In Search of Authenticity: Existentialism from Kierkegaard to Camus

Steven Churchill and Jack Reynolds, Jean-Paul Sartre, Key Concepts

Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness

Charles Taylor, The Ethics of Authenticity

Rousseau, Confessions

Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra

0 responses to “How To Be Yourself”

buy levofloxacin 500mg online – dutasteride pills order ranitidine 150mg online cheap