Switzerland – a tiny landlocked country in the middle of Europe – is underappreciated for its contributions to all of our histories – mine and yours included. It’s a extraordinary place, with an incredible history, and, it can teach us a lot, weirdly, about ourselves.

There is no place like it. Its variety of languages – French, German, Italian, Romansh – its mix of democratic institutions, its melting pot of cultures, its unique geography. One historian has claimed that it’s the oldest continuous true democracy.

I want to look at how Swiss history made it different and how it exported its lived ideas – political, cultural, liberal, romantic, democratic – through its most famous prodigal son to the rest of the world.

People have called themselves Swiss since at least the 15th century, and that loose confederation of what the Swiss call ‘cantons’ would soon become one of Europe’s most enduring, longest, most interesting, and cooperative ventures.

What’s fascinating about Switzerland is that, unlike the majority of countries in the world, it’s not really the product of natural borders – and that’s because it’s a very human creation.

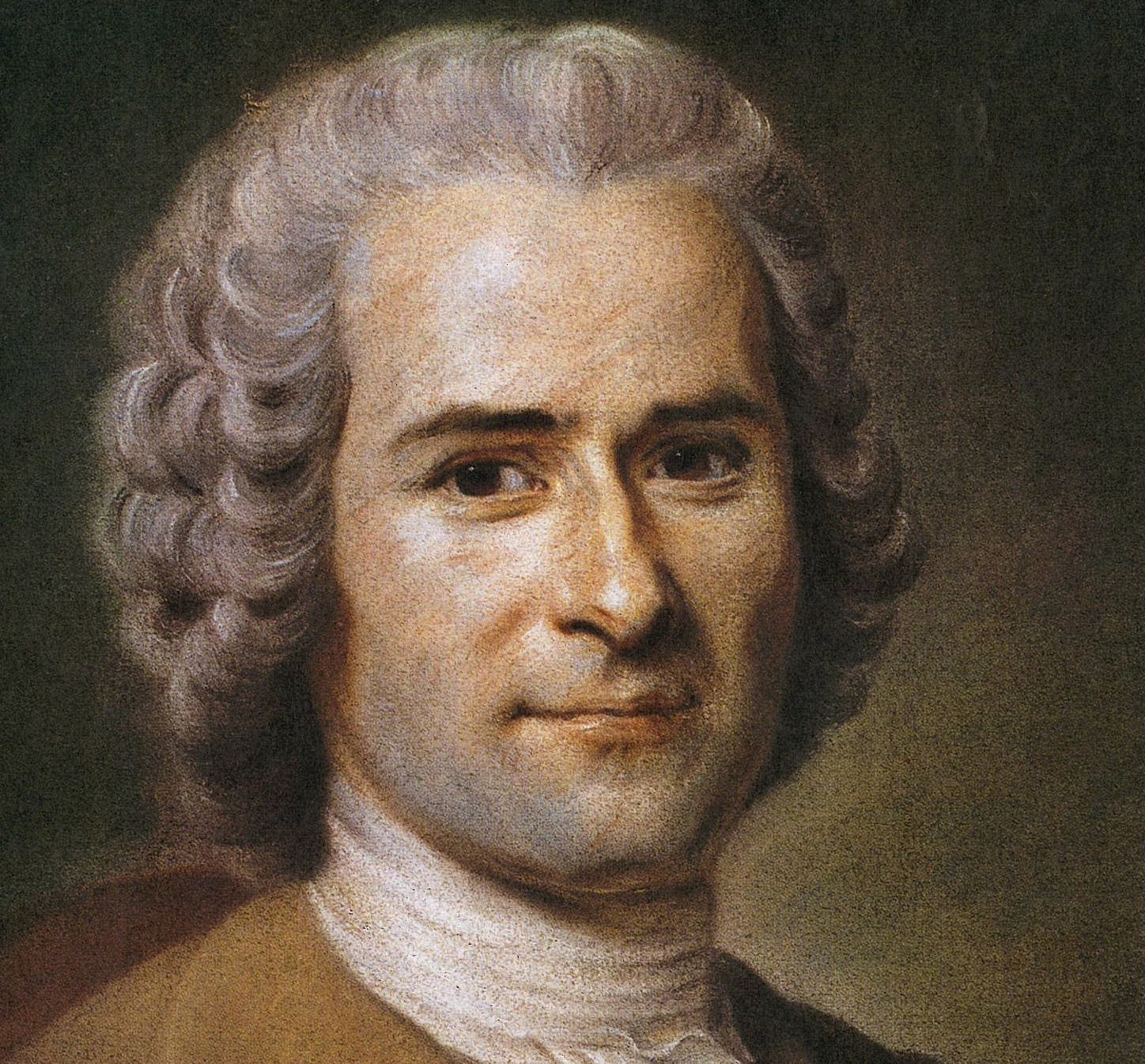

So I want to look at the long history that made the Swiss lovers of liberty and look at the thought of Jean-Jacques Rousseau – a man who could be claimed, quite reasonably, to be the most influential man to have ever lived.

Rousseau was the major influence on the French Revolution, the Romantic Revolution, on democracy, on every philosopher that came after him, on thinking about the individual, on literature and autobiography – he is, I think, the most fascinating figure of the Enlightenment.

The historian Robert Berki describes Rousseau as the ‘lynch-pin of the political consciousness of the entire modern period’.

And I’d say, more than politics, he’s the basis of much of the way we think about ourselves psychologically today. And he came from here – Geneva.

The historian Helena Rosenblatt calls Geneva the key to his thought. He signed his works, ‘citizen of Geneva’. Author Gaspart Vallette called the ‘spirit’ and ‘accent’ of his thought Genevan, and much of his work a ‘brochure’ to Geneva. And one philosopher has said that, ‘Geneva created Rousseau; it created the essence of his character’.

All of this raises a big question: how can a place influence a thinker that in turn influences the world, changing the very way we think about ourselves? Let’s find out.

In the Middle Ages, the area we now refer to as Switzerland was a loose conglomerate of different political bodies: lords, cities, monasteries, cathedrals, peasant communes, guilds, all with a complex and shifting constellation of different rights and privileges. It was part of the Holy Roman Empire but mostly left to its own devices.

By the thirteenth century, the great dynastic houses of Central Europe were failing to maintain order. The upkeep of things like roads, bridges, and local politics fell, in many places, to locals – abbeys, cities, or local lords.

Many village communities here in the Alps managed to retain their independence – organising politically amongst themselves – a rare level of autonomy for Europe at the time.

These ‘peasant and herder’ societies were known as strong warriors who maintained local solidarity which many historians refer to – in historians Clive Church and Randolph Head’s words – as the ‘backbone of Swiss autonomy’.

Steinberg writes that, ‘Everything was discussed openly at political assemblies’.

In the 19th century, as we’ll get to, the Romantics would idealise Swiss history as democratic, free, and wild, but how much of that is myth and how much reality?

Church and Head write that, ‘even where most arms-bearing males could attend public assemblies, a few clans typically monopolized offices and controlled most decisions’.

But despite this, the Swiss idea of freedom was very real and it would expand into something more powerful as Switzerland itself took shape as a modern nation.

Historian Jonathan Steinberg writes that the alpine herdsman lived ‘an archaic, independent, quasi-aristocratic form of life. They were free of feudal servitudes and, as a sign of their liberty, these mountain peasants bore arms and demanded ‘honour’ even from nobles’.

Much of their ideas, words, and phrases – words like ‘honour’ – came from the Roman occupation almost a millennium before.

Combine that with unique mountain conditions that required the maintenance of common pastures and important mountain passes, terrain that was very difficult for foreign forces to invade and occupy, and strong warriors on a high protein diet, and you get a potent recipe for freedom.

In the 13th century, fear of the dominant German house of Habsburg – who were beginning to dominate much of Central and Eastern Europe – pushed the much smaller Swiss regions towards cooperation.

In 1291, three cantons – Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden – signed a historic founding charter, which was only discovered 600 years later in the 18th century.

It read: ‘In order to preserve themselves and their possessions… in common council have with one voice sworn, agreed and determined that in the above named valleys we shall accept no judge nor recognise him in any way if he exercise his office for any reward or for money or if he is not one of our own and an inhabitant of the valleys’.

They called themselves eidgenossen, meaning ‘comrades of the oath’.

This type of alliance existed nowhere else in Europe. And it worked. In 1315 they fended off an attack from the Habsburgs.

This founding act spawned stories, songs, and mythologies of freedom – the beginning of an imagined community.

The Swiss now call it the Saga of Liberation, and many medieval stories of resistance – imagined and real – would be drawn upon as ammunition in fights against oppression; a mythology of Swiss freedom.

Peasant rebellions in 1489 and 1515 drew on the stories of the sage of liberation. During the peasant war of 1653 peasants organised themselves into local assembles drawing on the history of the 1291 ‘comrades of the oath’.

A story of William Tell – a Swiss Robin Hood – emerged. Tell was a legendary marksman who escaped from and led the resistance against a tyrannical Habsburg duke. Songs, poems, and stories have been written about him across the centuries.

Slowly, the alliance between the cantons grew, and more and more areas joined. Its foundations, for centuries, were simple: mutual aid, internal peace, defence, and no foreign interference.

But the medieval region was a mosaic of different cultures and ideas.

Steinberg writes that the old confederation was a marvellous ‘patchwork of overlapping jurisdictions, ancient customs, worm-eaten privileges and ceremonies, irregularities of custom, law, weights and measures’.

And the historian Julius Wyler writes that across the empire, ‘dynastic counties, ecclesiastic principalities, tiny castle baronies, free cities, and free peasant communities were interwoven in a colorful fabric’.

But in Switzerland in particular, at least the idea of democratic participation – despite being repressed by elites and aristocrats who would control local politics – continued to be strong.

Ultimately, as Church and Head write, ‘the privilege of all male citizens of communes to participate in decision-making, which retained great legitimacy in the Confederacy, set the Swiss apart from aristocratic Europe’.

By the time the Enlightenment hit Europe in the 17th century, Switzerland was a mix of aristocratic and oligarchic systems, all with hesitant or surface-level nods to democracy. Bern was an aristocracy, Zurich mixed city governance with a guild system dominated by craftsman, in Geneva a General Council of two hundred met each year to elect a Small Council, which elected four syndics, but the system was dominated by a small number of powerful families.

In short, Swiss cantons were mostly dominated by powerful interests, monopolised, controlled, while trying to pay lip service to the Swiss history of the idea of freedom.

Geneva was a contradictory place – full of different ideas – and certainly not a utopian republic, but the belief that it should be, or used to be, and that males had ancient privileges and rights to participate in political decisions – as in those stories of the Saga of Liberation – were a dominant presence in Genevan life.

Whenever its citizens could vote, only 1500 out of a population of 18,500 were given voting rights. And the direction of politics, the important decisions, were really dominated by a few powerful families.

One visitor said that it was being run like ‘a little fiefdom or dynasty’, and continued that, ‘this manner of acting displeases many people and one could even say that everyone is murmuring about’.

On top of this the emergence of capitalism, new industries, and banking began to increase inequality across the continent.

New money poured into Geneva – watch-making, cotton spinning, banking all developed – but in such a closed-knit city, some were questioning the utility of new ostentatious displays of wealth and luxury.

It sparked a debate about inequality and morality in the city.

The Church lamented the increasing in displays of wealth, with one theologian writing that it wasn’t a surprise if, ‘having degenerated from the simple and frugal life styles of our fathers, we have also degenerated from their virtues’.

Many blamed France, which Geneva borders, and the importation of French fashions – Frenchification.

Luxury was associated with indolence and vice, which, the criticism of commerce argued, was the opposite of what makes good citizens– modesty, frugality, and hard work.

A government report declared that, ‘everyday impurity, worldly vanity and luxury are growing. The present generation has completely degenerated from the frugality and piety of our ancestors and there is every indication that the evil is growing’.

Many cities and countries even had laws against owning, displaying, or wearing luxury goods – bans on certain fabrics, foods, and jewellery. But hypocritically, they were bans for everyone ‘except to those of the first quality’ as one law put it. Similar laws and exemptions applied across Europe.

The debate over whether commerce, wealth and luxury were a liability or a benefit was happening across the continent too. On one side, supporters said that trade and interaction between people and nations developed manners, politeness, and, of course, new comforts and wealth for everyone. Others argued it was pernicious, bred self-interest over virtue, envy and ambition, and led to the dismissing of traditional pious religious values.

The increasingly powerful bourgeoisie were arguing that the government were levying taxes against the people’s will, restricting liberty – that free trade and its rewards should be a benefit for all. The Genevan government supressed radical writing like this, while the Church warned of disorder.

Jean Jacques Rousseau was born in Geneva in 1712. I’m not going to understate how much I admire Rousseau. He was a difficult, contradictory, paradoxical, brilliant figure. The first modern critic of inequality. He laid the foundations for modern psychology, modern sovereignty of the people, of Romanticism, of ecology, he even wrote the first modern autobiography. He was a genius.

Rousseau grew up in Geneva while the debates about commerce, luxury, and democracy were spreading through the city, and much of it was taking place here in the Saint-Gervais watchmakers district where the Rousseaus lived.

Rousseau’s grandfather was a supporter of the new bourgeoisie fighting for rights against the Ancien Regime, and Historian Helena Rosenblatt writes that, ‘no other block in Geneva housed as many political agitators and demonstrators’.

Rousseau himself later wrote that, ‘from my most tender childhood, I had received principles, maxims, others would say prejudices, which have never completely deserted me’.

It’s likely that Rousseau was surrounded by stories about the Saga of Liberation and the idea that the democratic and republican principles of Geneva were being trampled on by its oligarchical rulers.

Rousseau soon left Geneva and immersed himself in the bourgeois intellectual salon life of Paris. But he came to dislike everything about elite French life.

And when in 1750 the Dijon Academy ran a competition offering a prize for the best essay answering the question, ‘Has the progress of the sciences and arts done more to corrupt morals or to improve them?’, he answered against the grain – progress, he said, wasn’t helping, it was corrupting morality.

In his celebrated ‘first discourse’, which catapulted him to fame overnight, Rousseau argued that the establishment life of sciences and arts makes people arrogant, the successful use their success to dominate, and the wise were turned, by the pursuit of wealth and status, into ‘base parasites’. He said that the arts and sciences ‘spread garlands of flowers over the iron chains’ of society.

He argued that society imposed on people models of ‘conformity’, ‘politeness ‘, ‘decorum’, and ‘ceremony’ at the expense of real virtue.

Rousseau said, ‘Jealousy, suspicion, fear, coldness, reserve, hate and fraud lie constantly concealed under that uniform and deceitful veil of politeness’.

The veil is all surface – a mask used for social climbing, rather than for the greater good.

He continued that, ‘we do not ask whether a book is useful, but whether it is well written. Rewards are lavished on wit and ingenuity, while virtue is left unhonoured. There are a thousand prizes for fine discourses, and none for good actions’.

In effect, praise amongst an in-group is more important that true virtuous actions. He saw high society life as a pecking order of sycophants. Civility for the sake of the powerful. A focus on reputation and status rather what’s good and true.

It’s a proto psychological argument because, like Freud, who very much admired Rousseau, he’s saying what appears on the surface is not always the truth of our actions and desires.

How often do you say something because it’s what your boss wants to hear? Be polite to superiors when you want to tell them what you think? Discovered that your motivations for doing something turned out to be different to what you thought they were at the time?

Rousseau wrote that, ‘Like the statue of Glaucus, which was so disfigured by time, seas, and tempests, that it looked more like a wild beast than a god, the human soul, altered in society by a thousand causes perpetually recurring, by the acquisition of a multitude of truths and errors, by the changes happening to the constitution of the body, and by the continual jarring of the passions, has, so to speak, changed in appearance, so as to be hardly recognizable’.

Rousseau is significant because at the time, most people had assumed humans have a fixed, essential make-up – a human nature – and one that persisted across time. Rousseau is arguing for something new and revolutionary – that human experience changes over history.

He despised the inequality he saw growing everywhere, arguing that while some inequality was natural, ‘men are not naturally kings, or lords, or courtiers, or rich men. All are born naked and poor; all are subject to the miseries of life, to sorrows, ills, needs, and pains of every kind’.

He thought that inequality that came from our natural strengths and weaknesses was justified, but that those inequalities that come from privilege, money, power lead to us wearing those veils, an inauthentic experience. He asked, ‘what will become of virtue when one must get rich at any price?’.

He wrote that ‘insatiable ambition’, ‘thirst of raising their fortunes’ and the ‘desire to surpass others’ inspired all to ‘injure one another’ with a ‘secret jealousy’ and a ‘mask of benevolence’.

Rousseau thought that we were happier in nature, and that the emergence of society from a state of nature meant, ‘all ran headlong to their chains, in hopes of securing their liberty’.

Instead of liberty, ‘we have nothing to show for ourselves but a frivolous and deceitful appearance, honour without virtue, reason without wisdom, and pleasure without happiness’.

This idea of a mask or veil of status we all wear meant he was also one of the first thinkers of what we now refer to as ideology, which is why Rousseau is a forerunner for much of the thought that came after him.

He said, ‘suspicions, offences, fears, coldness, reserve, hate, betrayal will constantly hide under that uniform and flase veil of politeness’.

He attacked those who thought that wealth, luxury, and commerce were bringing virtue to Europe – and had many enemies across the continent – signing the essay, ‘citizen of Geneva’.

To many in Geneva it seemed that Rousseau was right. New wealth did not seem to be improving the morals of city. Patriotism, many argued, was being replaced with selfishness. Citizenship in Geneva was being sold to the highest bidder. Prostitution was on the rise, children increasingly born out of wedlock, drunkenness and vanity were endemic. One Genevan wrote that the rich ‘abandon themselves to arrogance’. They were accused of ‘buying the republic’.

Rousseau later wrote in his autobiography that when he returned to Geneva, its ideas of laws and liberty were not as ‘clear cut as I would have wished’. And he wrote time and again that he just wished to be useful to his native city, drawing out the Republican spirit, finding a foundation for virtue, good morals, and ethical governance.

Rousseau’s theory led naturally to a question: if society corrupted people, what was it in us that was being corrupted? What were people like before entering society? Where did goodness reside?

The dominant theory was that man was born wicked and made good by society, people were socialised. Rousseau turned this on its head.

He wrote in a letter that, ‘the question is to examine the hidden, but very real relations which exist between the nature of government and the genius, morals, and knowledge of citizens; and this would involve me in delicate discussions… this research is good to do in Geneva’.

But Rousseau spent the summer of 1754 in the city digesting new material for what would become his magnum opus – The Social Contract.

In the book that was going to become an almost unsurpassed influence on the history of Europe, arming the French revolutionaries and inspiring democratic thinkers and movements for centuries to come, Rousseau, in a flick of the pen, changed the definition of a concept central to how we think about politics: sovereignty.

At the time, the standard view was that the sovereign was the monarch, and that the monarch was sovereign for two reasons. The first was that the people had handed over some of their freedom in exchange for security. The second reason was that god had willed that the monarch had a divine right. This was the basis of Ancien Regime politics. For example, Louis XV had said, ‘It is in my person alone that sovereign power resides’.

In Geneva, the elitist patrician government had argued that handing power to the people would lead to chaos and disorder, in the politician Jean-Robert Chouet’s words, ‘continuous peril’.

Influentially, the patrician Jacob de Chapeau Rouge argued that: ‘The best type of government, and the most favourable to liberty, is that of an elite council, composed of the most wiser, enlightened, and important citizens, in small enough number to avoid the inconveniences of the multitude’.

He talked of the ‘ignorance of the little people and the passions by which is so easily allows itself to be carried away’.

In response, the politician Pierre Fatio argued that that Greeks and Romans assembled up to 20,000 people three times a month. Assemblies of the people were ‘one of the principal supports of liberty’.

Fatio was eventually executed by Geneva’s patrician leaders, and his supporters were tortured and hanged. Rousseau’s grandfather was amongst those punished. Geneva’s ruling patricians accused the people of insubordination and disloyalty to the city. Being good citizens and obeying leaders was a duty.

This was the era of pamphleteering, of increased literacy, of journals and philosophy. In 1718 what came to be known as the ‘anonymous letters’ circulated around the city, arguing that Genevans had historically been a ‘free people’, that their rights were being trampled on, that the general council had traditionally had to approve legislation and had the right to assemble every 5 years, all of this being ‘one of the principle supports of its liberty’.

The anonymous letters were denounced as ‘tending towards anarchy, full of seditious maxims against all governments’. Assemblies were forbidden. The patricians argued that Rome perished by the ‘very hands of the people’, and that these pernicious letters would lead to confusion and disorder, eventually leading to tyranny. The council looked after the citizenry, who should be grateful and happy.

Rousseau took aim at the Ancien Regime of patrician rulers and the rising power of the bourgeoisie at the same time. Both forgot something important – it wasn’t the monarch that was sovereign, it was the people.

His 1762 book The Social Contract sent shockwaves across Europe and is famous for declaring that, ‘Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains’.

The most popular view of the time – which came from Enlightenment thinkers like Thomas Hobbes and John Locke – and one that the rulers of Geneva relied on, was that when we emerge from a state of nature and enter into society we necessarily give up a part of our freedom, handing it over to a king or ruler, in exchange for protection, security and ‘civil’ society. In doing so, the ruler becomes the sovereign. Hobbes said that without this, we would be in a war of all against all.

Rousseau despised this idea. It wasn’t the king, the patrician, the aristocrat, that was sovereign, it was the people, because it is impossible to truly give up your own freedom.

As Helena Rosenblatt writes, this is one of Rousseau’s most important ideas: ‘a popular sovereign composed of all the people, to which the government magistrates are accountable as “simple officers,” charged only with “the execution of the laws” passed by the sovereign’.

Rousseau wrote, ‘The people, being subject to the laws, ought to be their author’.

His work then set upon a difficult task: it tried to explore how a multitude of individuals could come together into a community of people. He was worried about the selfish individualism fostered by bourgeois life as much as the tyranny the bourgeois were fighting against.

Each, he said, when they come together in a community, is an ‘indivisible part of the whole’.

From this emerged his most enduring idea: the general will. The general will ‘must both come from all and apply to all’.

He said that if each gives themselves over to the sovereign body, then each is as free as each other, and no-one should have any interest in oppressing or restricting the freedom of another. In other words, all should be equal before the law.

Rousseau thought that people coming together in small city-state like assemblies – of the sort found in Switzerland – was the best form of democracy, but that often being impossible in modern societies, he favours what he calls ‘elective aristocracy’ – what we’d call representative democracy – which is meant to be the rule of the wisest in service of the general will of the people.

This all sounds quite obvious to us now, but that’s only because Rousseau made it so. He single-handedly made the people sovereign, and the government servants of the people, and just a few decades later, after he died, became one of the intellectual backbones of the French Revolution, and continues to be one of the central philosophical sources for how we think about democracy today.

Back in Geneva, Rousseau was both loved and loathed. One citizen wrote thank you ‘for the present you have given us… It is an arsenal of the most excellent weapons’.

One of his allies in Geneva wrote to him that his books were widely read and that, ‘even your enemies are forced to admit that [..] your genius is displayed with most vigor! Your work must frighten tyrants, born and unborn. It makes liberty ferment in all hearts’.

But The Social Contract was banned by the authorities, caused an uproar across Europe, and was burned in France. Rousseau was forced into exile.

Rousseau was a wonderful contradiction. He was a success in a society that he despised. He wrote the first modern autobiography, ruthlessly examining his own faults. He was a playwright who argued against the theatre. He believed in natural goodness but failed, in many ways, to live a good life. He lost friend after friend in quarrel after quarrel. He tried to be a thinker of both individuality and community. He was, and still is, both worshipped and hated. But he was, undeniably, a genius.

He tried honestly to tackle the contradictions of the emerging modern world, which he saw so distinctly in his home city – community versus capitalism, elites versus new money, consumerism versus virtue, nature versus civilization – the paradoxes of modernity.

The sources of great European rivers – the Rhone, the Rhine, tributaries of the Danube and the Po, all spring from the Swiss mountains. And so did much of the discourse, history, and debate that framed, and still frames, our debates about modern life.

The American Founding Fathers drew on Swiss history and politics when framing their own independence. His thought leads to Kant, Hegel and Marx. Robespierre read him religiously. Historian Thomas MacFarland writes that Rousseau ‘may well have been the most important cultural figure of the last quarter millennium’. And he was the father of Romanticism, what the philosopher Isiah Berlin called ‘the greatest single shift in the consciousness of the West’.

And historical literature is full of inspired travellers eloping and pilgrimaging and exploring Switzerland while reading Rousseau.

He put Switzerland on the map for aristocrats on the ‘grand tour’ of Europe. By the early 19th century, travel guides were printed that included engravings illustrating Rousseau’s house on the Ille St Pierre, one of Rousseau in his garden, and scenes from his autobiography.

The Romantics took from Rousseau his interest in what humans were like outside of the corrupting influence of society, asking what authentic man was, uncorrupted by the seeking of status. He put the individual’s freedom at the core of his thinking, and in doing so – in all his writings – explored individual passions and character and nature at the same time as our political communal life.

The English Romantic poet Wordsworth set off on a walking tour from England to the Swiss Alps in 1790 under the influence of Rousseau. And Shelley read his novel The New Heloise with Byron on Lake Geneva, taking a boat trip that Rousseau himself took.

Richard Fralin has written that, ‘Geneva was both the starting point and the finishing point, the inspiration and the goal of Rousseau’s political thought’.

It reminds us how much of what we think of as abstract ideas somewhere in dusty books or in disappearing conversations is actually rooted in place, real lives, in bricks and mortar, in rocks and concrete in history. We too often forget that.

I’ll leave you with the words of Rousseau himself, who, in writing about his work, said:

here is the history of the government of Geneva. Is it not word for word the image of our republic, since its birth until today? I therefore took your Constitution, which I found good, as a model of political institutions, and proposing you as an example to Europe

Sources

Jonathan Steinberg, Why Switzerland?

Clive H. Church and Randolph C. Head, A Concise History of Switzerland

Helena Rosenblatt, Rousseau and Geneva: From the First Discourse to the Social Contract

Leo Damrosch, Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Restless Genius

Nicholas Dent, Rousseau

Rousseau, Reveries of a Solitary Walker

Marc H. Lerner, A Laboratory of Liberty, The Transformation of Political Culture in Republican Switzerland

Rousseau, The Basic Political Writings

Julius Wyler, The Formation of the Swiss Democracy

Thomas McFarland, Romanticism and the Heritage of Rousseau

0 responses to “How Switzerland Changed the World”

buy nexium 20mg online – imitrex over the counter buy imitrex 50mg generic