There are many ways of thinking about history. Today, I want to talk about Putin’s sense of Russian history in comparison to an assumption about history that we often adopt in the West. I think, ironically, it is our sense of history that’s mistaken, and while Putin draws the wrong conclusions, his diagnosis of history – the model of history he’s a product of – contains some surprising truths.

Russia’s difficult relationship with Europe and its strained and unique relationship with its own identity has a long history that goes back long before Putin, but it is an identity he believes in, and is strengthening some of its elements. It has a rich tradition, as we’ll see, in philosophy, poetry, literature, in anti-rationalism, romanticism. And I think, if we approach it carefully, it can teach us a lot about what our model of history often leaves out.

‘‘Our land is rich, but there is no order in it’, they used to say in Russia. Nobody will say such things about us any more’ – Putin (2000).

We often adopt a model of history in Europe and America that historian Timothy Snyder calls the politics of inevitably. It has come in various forms: Hegel and Marx’s dialectics, the idea of an ever progressing linear historical path, what used to be called Whiggish history, Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History – the argument that after the fall of the Soviet Union the liberal model was the end point of historical progress. The assumption, often, is that progress is inevitable, automatic, and out of our human hands.

Snyder says that it’s ‘a sense that the future is just more of the present, that the laws of progress are known, that there are no alternatives, and therefore nothing really to be done’.

If history is something that happens automatically, the politics of inevitably doesn’t need anyone to do anything, it doesn’t need ideas, it doesn’t need action, it doesn’t need fighting for or defending. History, like an escalator to freedom or a journey floating down a river, just is.

Snyder continues that, ‘The politics of inevitability is the idea that there are no ideas. Those in its thrall deny that ideas matter, proving only that they are in the grip of a powerful one. The cliché of the politics of inevitability is that “there are no alternatives.” To accept this is to deny individual responsibility for seeing history and making change. Life becomes a sleepwalk to a premarked grave in a prepurchased plot’.

The politics of inevitability gives the impression that once certain conditions are met: markets, property rights, freedom of speech, class-consciousness, maybe, freedom will flourish automatically.

This idea comes from many places – you could say it goes back to the biblical idea of millenarianism – that life on earth will get progressively worse until Christ returns and reigns over a golden age of 1000 years.

But in its modern form, its roots can be found in the idea of universality during the Enlightenment. There, again, it was interpreted in many ways – Voltaire believed in commerce expanding across the world, the global businessman, Leibnitz believed in a universal language, Kant thought there was a universal model of morality that everyone should adopt, Marx believed in a universal concept of history. They believed these things were inevitably true, independent of individual people.

Author Pankaj Mishra writes that the rationalist idea of the Enlightenment which we’re all a product of presented ‘a unified project of individual emancipation, inaugurating the necessary and inevitable passage of humankind from tradition to modernity, immaturity to adulthood’.

What this meant was that when each nation, country, group or individual discovered, understood, and accepted these universal truths, they would inevitably ‘catch-up’ with countries like England and France who were already on the road of inexorable progress. And as Snyder argues, most of us in the West still tacitly accept this model.

But on a parallel track, but still with its roots in the Enlightenment, runs a different model, a counter-model, a powerful critique, one that might be summarised as anti-rationalist.

The adherents of the model were people like Rousseau, Herder, Dostoevsky, and Nietzsche, and they criticised the universal idea of history in different ways.

Take one part of an opposing view: the idea of a national identity. It’s the idea that what defines a people’s character, their essence, their spirit, is not reason or enlightened individuals approaching the world with cold logic, but a pre-supposed integral national identity.

The sociologist Liah Greenfeld has argued that, in fact, more than the escalator of expanding rationalism and freedom, nationalism – national identity – is the most fundamental factor for understanding how the world we live in developed. And, ironically, there is a logic to how national identities have developed.

Imagine two countries. France and England, during the Enlightenment, say. Some French thinkers argue that England is ahead of France – economically, culturally, spiritually. There are two main ways France can respond.

First, they could argue that England is on the right track – the one universal track forward – and emulate England in a bid to catch up.

Alternatively, they could argue that while England is ahead, France is on a different track, a better track. They could argue that history has multiple tracks going in different directions, there’s no right or wrong track, and in fact, our track may be behind now but once we develop it, it’s a better track, a stronger and faster track.

In her now celebrated study, Greenfeld argues that, rather than the first universal model, comparison and resentment between developing nations has been a central force driving history. Resentment, she says, following Nietzsche, is, ‘a psychological state resulting from suppressed feelings of envy and hatred’. She argues that nations have often interpreted the values of stronger nations as inappropriate, wrong-headed, dangerous, and that this, in turn, has fuelled the development of new internal national values. This has happened many times in history, but most significantly it happened in Germany and Russia.

Germany and Russia both came late to modernity, and they both looked westward for emulation and inward for inspiration.

Throughout the 18th century, the Russian tsars Peter the Great and Catherine the Great were both modernisers, importing European ideas, strategies, political models, philosophies, and sciences, while also purposively fostering a new sense of Russian national identity.

Peter the Great was the first monarch to refer to Russia as a fatherland. He built secular schools, reformed many of Russia’s institutions, imported European military tactics and even enforced dress codes and etiquette, implementing a tax on beards to encourage a Western style. Many of Peter’s officers travelled abroad and were introduced to Enlightenment ideas.

The poet and playwright Alexander Sumarokov asked, ‘You, travelers, who visited Paris and London, tell me! do people there crunch nuts while watching Drama; and when the performance is on the stage, do they whip drunken and quarreling coachmen, causing alarm to the floor, balconies, and the whole theater?’.

Catherine the Great continued Peter’s project, wanting to develop an enlightened Russian middle class. Catherine corresponded with Voltaire and met Diderot and paid D’Alembert to tutor her heir. She read Montesquieu and became known, like Peter, as an enlightened despot.

Voltaire wrote that Russia under Peter the Great ‘represented perhaps the greatest époque in European life since the discovery of the New World’.

Catherine let the philosophes publish their work in Russia when they were banned in France, she argued for equality under the law, and she founded new schools.

But it was the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau who first became critical. He wrote that Peter ‘wished to produce at once Germans or Englishmen, when he should have begun by making Russians; he prevented his subjects from ever becoming what they might have been, by persuading them that they were what they were not. It is in this way that a French tutor trains his pupils to shine for a moment in childhood, and then to be forever a nonentity’.

In Russia, intellectuals began having a strained relationship with their own sense of inferiority to the countries they were attempting to emulate. Greenfeld argues that a feeling of inferiority can only last so long, and can quickly turn to ressentiment. She argues there are two common responses to socio-political problems within a nation: shame and denial.

She writes, ‘Shame is a rare reaction: given how singularly unpleasant this feeling is, it must be difficult to sustain it over a period of time of any length’.

Instead, many Russian intellectuals and politicians denied that they were further behind on the same singular path.

For example, the playwright Denis Ivanovich Fonvizin asked, ‘How can we remedy the two contradictory and most harmful prejudices: the first, that everything with us is awful, while in foreign lands everything is good; the second, that in foreign lands everything is awful, and with us everything is good?’.

The writer and father of Russian socialism, Alexander Herzen, wrote, ‘Like Janus, or like a two-headed eagle, we were looking in different directions while a single heart was beating in us’.

If the example set by Europe was to be rejected, Russians had to turn inwards and develop a Russian consciousness, a Russian spirit, a different path for Russia. And so the Russian language was developed through literature and poetry. Pride was fostered through the Church Slavic that distanced Eastern Orthodox Christianity from the Latin that was used in churches in Europe. National histories were written.

Karamzin wrote, ‘Look: become equal to them, and then, if you can, surpass them!’.

He continued, ‘We had our own Charlemagne: Vladimir. Our own Louis XI: Tsar loann. Our own Cromwell: Godunov. And in addition such a Ruler, whose like is nowhere to be found: Peter the Great’.

Russian intellectuals became critical of European standards, arguing they shouldn’t be emulated at all.

Fonvizin wrote after a trip to Paris that, ‘One has to renounce all common sense and truth to say that there is not much of what is very good and deserving of imitation here’.

He said, ‘a Frenchman would never forgive himself if he ever missed an opportunity to cheat… His God is money… D’ Alemberts, Diderots, in their own way, are as much charlatans as those I meet every day on the streets; all of them are cheating people for money, and the difference between a charlatan and a philosophe is ‘only such that the latter to his greed adds an unparalleled vanity”.

He recommended Russians feel pride in their own ways: ‘A cattle-yard in the holdings of our honest gentry is much cleaner than [streets] in front of the very palaces of the French kings’.

Karamzin said ‘So let us honor and glorify Our language, which in its natural richness, almost without any alien admixture, flows like a proud, majestic river-roars, thunders-and suddenly, if need be, softens, murmurs like a tender brook and sweetly pours into one’s soul, forming all the rhythms which may be contained in the falling and rising of a human voice’.

Of course, this phenomenon was not unique to Russia. In fact, it started in France with Rousseau and spread to Germany through the Romantics. It could be argued that it found its most distinctive form in Russian culture, but can be found all over the world.

Rousseau’s emphasis on feeling, emotion, on localism, on culture, and on the community was picked up by young discontented provincials in a not yet unified Germany that was lagging behind the rest of the Europe.

Mishra writes that German writers like Herder and Fichte ‘simmered with resentment against a largely metropolitan civilization of slick movers and shakers that seemed to deny them a rooted and authentic existence’.

Romantics in Germany who felt resentful of French dominance and Enlightenment rationalism responded by imagining an authentic German culture and volk.

The German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder criticised the rationalist philosophes, writing that, ‘as a rule, the philosopher is never more of an ass than when he most confidently wishes to play God; when with remarkable assurance, he pronounces on the perfection of the world, wholly convinced that everything moves just so, in a nice, straight line, that every succeeding generation reaches perfection in a completely linear progression, according to his ideals of virtue and happiness’.

He asked Germans to ‘Spew out the ugly slime of the Seine. Speak German, O you German!’.

The discontented romantics responded to a modernity where, as Marx argued, ‘everything that’s solid melts into air’, and instead emphasised national myths and fables, religion, local culture, poetry and song, by romanticising the local landscapes and emphasising the feelings of downtrodden commoners trampled on by the swiftsteel boots of modern commerce, modern factories, modern assumptions. The Romantics contrasted the cold calculations of reason and logic and reflection with the real experience of every day life, with the immeasurable, the qualitative, the spontaneous, the exciting.

In Russia many turned to and emphasised collective ideas, ethnicity, blood and soil, the Russian soul, the unified people, pan-Slavism.

The poet Nikolai Lvov wrote that, ‘In foreign lands all goes according to plan, words are weighed, steps are measured. There one sits hour upon hour; then begins to think. Having thought, one rests. Having rested, one smokes a pipe. Then, thoughtfully, goes to one’s work. There are no songs, no pranks. Among us, Orthodox, however, work is like fire under our hands. Our speech is thunder, so that the sparks fly and the dust rises in columns’.

A common theme was unity, oneness, harmony.

Since the Reformation, western churches had moved towards the individual, emphasising the individual’s relationship to God. The Russian Church instead emphasised sobornost – ‘the idea of unity in multiplicity’, in the Russian theologian Khomyakov’s words.

‘The Church is one’, he wrote. ‘her unity follows of necessity from the unity of God; for the Church is not a multitude of persons in their separate individuality, but a unity of the grace of God, living in the multitude of rational creatures, submitting themselves willingly to grace’.

This thinking applied to Russian communes too.

‘A commune’, wrote Sergey Aksakov, ‘is a union of the people who have renounced their egoism, their individuality, and who express their common accord; this is an act of love… in the commune the individual is not lost, but renounces his exclusiveness in favor of the general accord-and there arises the noble phenomenon of a harmonious, joint existence of rational beings (consciousness): there arises a brotherhood, a commune-a triumph of human spirit’.

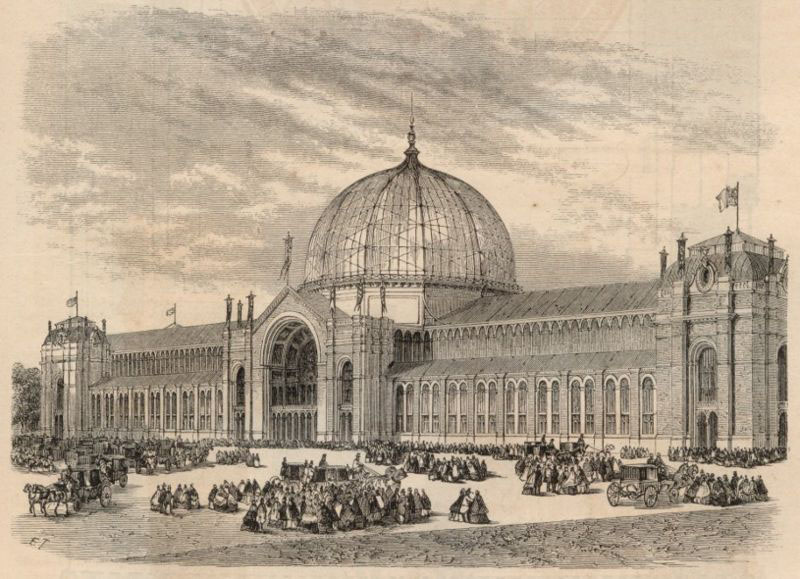

And before publishing his first major work – Notes From Underground – Dostoevsky went on a tour of Europe. In London he visited the International Exhibition at the Crystal Palace, a grand fair of world products and the grandest example of Western commerce, individualism, and capitalism.

He wrote, ‘You become aware of a colossal idea; you sense that here something has been achieved, that here there is victory and triumph. You even begin vaguely to fear something’.

He then wondered, ‘Must you accept this as the final truth and forever hold your peace? It is all so solemn, triumphant, and proud that you gasp for breath’.

He continued: ‘Look at these hundreds of thousands, these millions of people humbly streaming here from all over the face of the earth. People come with a single thought, quietly, relentlessly, mutely thronging into this colossal palace; and you feel that something final has taken place here, that something has come to an end’.

But in London Dostoevsky saw poor people ‘half-naked, savage, and hungry’. He saw that liberty only existed for the rich. He worried about ‘a principle of individualism, a principle of isolation, of intense self-preservation, of personal gain, of self-determination, of the I, of opposing this I to all nature and the rest of mankind as an independent autonomous principle entirely equal and equivalent to all that exists outside itself’.

He returned to Russia with his mind made up: Russians shouldn’t mindlessly import European ideals. Nietzsche read the book Dostoevsky wrote next, Notes from Underground, and from it derived his own idea: it wasn’t reason or divine truth that drove world history, it was ressentiment.

First, no one knows exactly what Putin is thinking, who he really admires, what his true motivations are. And I’m not saying he’s consciously adopted this tradition or model of history. It is important though to understand the trend that he’s in many ways a part of and is able to draw from.

These anti-western, anti-liberal, anti-rationalist – there are many ways to frame them – sentiments became even more fertile in Russia during the crises of the 1990s when Russia was plunged into internal conflict, gangs rose, hyperinflation happened, provinces ignored Moscow or even declared independence – in short, Russia was in chaos.

In 2013, Putin said, ‘the question of finding and strengthening national identity is of a fundamental nature for Russia’.

Scholar Sergei Medvedev has written that in the 2000s, ‘ressentiment was transformed into state policy’, through the propagation of a ‘myth of geopolitical defeat, humiliation and pillaging of Russia by world liberalism and its henchmen Yeltsin, Gaidar and Chubais’.

He continues, ‘All of Russian society, from Putin to the last pointsman are all equally the bearers of ressentiment. For Putin the source is the non-recognition of himself and of Russia as equal and respected players on the world stage; for the pointsman – his helplessness in the face of the police, officials, courts and bandits. The ressentiment fantasies of the authorities at a certain moment entered into a strange resonance with the ressentiment fantasies of ordinary people’.

A conservative orthodox publication asked in 2005, ‘Is it possible to satisfy [the West]? Is it possible to ever be recognized as equals? […] And so we wait quietly for them to let us become like they are, to let us into the club of equals. But the answer is: Never’.

This new wave of resentment has led to the adoption of two thinkers that carry this historical tradition into modern conservative Russian culture: Carl Schmitt and Ivan Illyin.

The German philosopher Carl Schmitt was a conservative and fascist thinker who was a member of the Nazi party. His work responded to the crisis of democracy in Weimar Germany in the interwar period before the Nazis took power.

Schmitt was, to put it simply, a philosopher of order. He saw liberalism in interwar Germany as leading to all the things that Russians were seeing in the 1990s – hyperinflation, depravity, chaos.

He saw liberal democracy as fundamentally flawed because it couldn’t deal with the political conflict that is inherent in all politics. Under liberal democracy, no single person or party was strong enough to prevent that conflict. And in fact, Schmitt thought, liberal rights handed the enemies of liberalism the tools that could be used to destroy liberalism.

He said, ‘the organizations of individual freedom were used like knives by anti-individualistic forces to cut up the leviathan and divide his flesh among themselves’.

Instead, he sought to homogenise the masses through the single will of a sovereign.

He thought a strong leader should stand above the law in a ‘state of exception’ so that disorder could be dealt with more effectively.

After the chaos of the 1990s, as political theorist David Lewis states, ‘Carl Schmitt’s influence became one of the most important influences in Russian conservatism in the 2000s’.

The other philosopher that Putin has specifically quoted is the conservative spiritual thinker Ivan Illyin, a counter-revolutionary who admired Mussolini and Hitler. Putin even reburied Illyin in a ceremony in 2005.

Illyin’s philosophy looked backwards to a time when God, the world and the universe were united as one. Like Schmitt, Illyin criticised the individualistic, disjointed, morally relative worldview of liberalism.

He thought that God had made a mistake by dividing himself and the world up into parts. He wrote, ‘When God sank into empirical existence he was deprived of his harmonious unity, logical reason, and organizational purpose’.

He continued: ‘the empirical fragmentation of human existence is an incorrect, a transitory, and a metaphysically untrue condition of the world’.

Illyin saw the nation as a single organism, and he simply thought Russia was at its centre. God was Russian. Ukraine was Russian. The truth was eternally in the past. And a single leader must lead. Anything from outside of this eternal truth was a threat.

He said that Mussolini, ‘hardens himself in just and manly service. He is inspired by the spirit of totality rather than by a particular personal or party motivation. He stands alone and goes alone because he sees the future of politics and knows what must be done’.

The Russian film-maker Nikita Mikhalkov introduced Illyin to Putin. Mikhalkov himself wrote that Russia was a ‘spiritual-material unity’ that was at the centre of Eurasia, ‘an independent, cultural-historic continent, organic, national unity, geopolitical and sacred, center of the world’.

Putin, similarly, has said that, ‘The Great Russian mission is to unify and bind civilization. In such a state civilization there are no national minorities, and the principle of recognition of ‘friend or foe’ is defined on the basis of a common culture’.

Like Schmitt, Illyin argued that porizvol – lawlessness of the leader – was better than a leader under the law. The leader was the exception to the law. Putin has also spoken of a ‘dictatorship of the law’.

This is a complicated history. The linear universalistic rationalist model of history assumes that chaos moves inevitably towards an ordered Enlightenment society. I think what history actually shows is that chaos that sometimes arises from those very things is just as likely to create the conditions for this nationalistic-conservative-spiritualistic authoritarianism that we see in parts of Russian intellectual life. And, to call a spade a spade, it is fascism. Of course, much of what I’ve painted here is a generalisation, and there are many sides to history – Russian and elsewhere.

We have to take a nuanced view of history like this: we have to understand that those things that don’t fit neatly in our liberal, rationalist, utility-maximising, logical model – those romantic elements – national identity, spirit, feeling, locality, language, culture, poetry – are both part of us, part of what’s driven history, and are the things that – like bundles of sticks of latent tinder – can be twisted into authoritarianism, into expansionism, into fascism.

Sources

Pankaj Mishra, Age of Anger: A History of the Present

Timothy Snyder, The Road to Unfreedom

Liah Greenfeld, Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity

David Lewis, Russia’s New Authoritarianism

0 responses to “Putin’s Sense of Russian History”

levaquin 250mg pills – order dutasteride generic oral zantac 150mg