I’m in Germany, thinking about how Germany changed the course of history. No – it’s not what you’re thinking of. Germany gave us some of the most influential philosophers – Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche, Marx, Schopenhauer, Heidegger. Why?

In fact, for good or for bad, many of the ideas and problems of modern life – a focus on the individual, a concern with industrialism, a focus on nations and national identity, even the idea of a rebellious spirit – arose out of a small area in the middle of a yet-to-be-unified Germany. In this small area emerged both a crucible of modernity and a reaction to it.

The story starts with the Enlightenment. Because during those tumultuous years, Germany became a great critic of the dominant cultures that surrounded it – British and French culture, in particular.

I want to look at how that critical culture emerged, take a quick look at the irrationalist and romantic philosophies that it produced, ask what they gave us, what they got right, how they might still help us, and how they’re an important part of our model of human behaviour today.

Germany has a complicated history. Whereas Britain & France have a claim on having a reasonably singular narrative, Germany’s is fragmented. There is no single national story. The Germanic area was made up of a loose collection of principalities and states that weren’t united until 1871.

Goethe – Germany’s answer to Shakespeare wrote, ‘Germany? Where is it? / I do not know where to find such a country’.

The Bavarians, for example, fought with the French during the Napoleonic Wars. And before that, the Germanic people had been traumatised by the widespread devastation of the Thirty Years’ War, which largely took place on German soil, and included every major European power as well as complex alliances of different states and monarchies, leagues, empires, and principalities. Around twenty percent of Europe’s population died during the war – in some areas it was as high as 60%.

So, German was fractured. But its real modern history begins with a reaction. France was the great enlightened, powerful, and dominant culture of the enlightenment. Britain had its empiricists, scientists, and growing empire. Germany didn’t have much going for it.

It had an inferiority complex and was invaded by Napoleon, being occupied in totality by 1812. The Germans were forced to fight for the French in Russia. But it was a complicated situation. Many young radicals were supporters of the revolution in France, and liberty was the call of the day. Then Napoleon came.

Many went from celebrating Napoleon to hating him, went from wanting to be French to wanting to be rid of the French.

This complex resentment of the French philosophes and French authority led to a flourishing of German ideas that emerged as a reaction to the Enlightenment – which many German thinkers characterised as overbearing, condescending, a building of systems of domination. It wasn’t rejected – Kant, of course, was German – but modern theories of philosophy began to take on a different shape in Germany.

But the shape the German response took needed its own fertile soil – some ideas to build with that were, well, German. And where better to find them than in the soil?

The ideas of the Enlightenment – whether in Kant’s system of rationality, Newton’s scientific laws of gravity and motion, or Spinoza’s all-regulating metaphysics – were felt by many German thinkers to be distant, abstract, and cold theories. They seemed to be completely void of the vitality of ordinary life; too concerned with mathematics and technical language than with the felt immediacy of ordinary routines, the vicissitudes, colours, and passions of human existence.

And so, German thinkers began to look both at their close surroundings, and inwards.

The ideas first took root in two places – the German language and the German landscape – and went on to emphasise other immediate, close phenomenon that the French philosophes often neglected – emotion, the irrational or undecidable, sentiment, folk stories, mystery, the everyday and the ordinary.

When the father of the Reformation, Martin Luther, first translated the bible into German in 1534, he focused on everyday German language – a bold move at a time when the Church had been dominated by an exclusive high Latin. His new bible became an instant best seller, setting off a revolution in reading and a flourishing of the German language.

In many ways, Germany’s inferiority complex – with no colonies, centralised state, national newspapers – led to a insatiable appetite for books. The German people took refuge in the imagination more than anywhere else in Europe.

Goethe said, ‘the honorable public knows the extraordinary only through the novel’.

Tieck translated the great adventure novel Don Quixote into German.

Books, of course, have the miraculous effect of turning the attention and imagination inward to the self and outward to another mind and world simultaneously.

Germans had also long instilled great significance in the landscape around them – in particular, the forest.

The forest was powerful, life-giving, contradictory, beautiful, and dangerous all at once. It was pregnant with mystery, midwife to history, a symbol of nature and life but also darkness and fear. Later, Grimm’s German fairy tales were almost always set in the woods that covered much of the country.

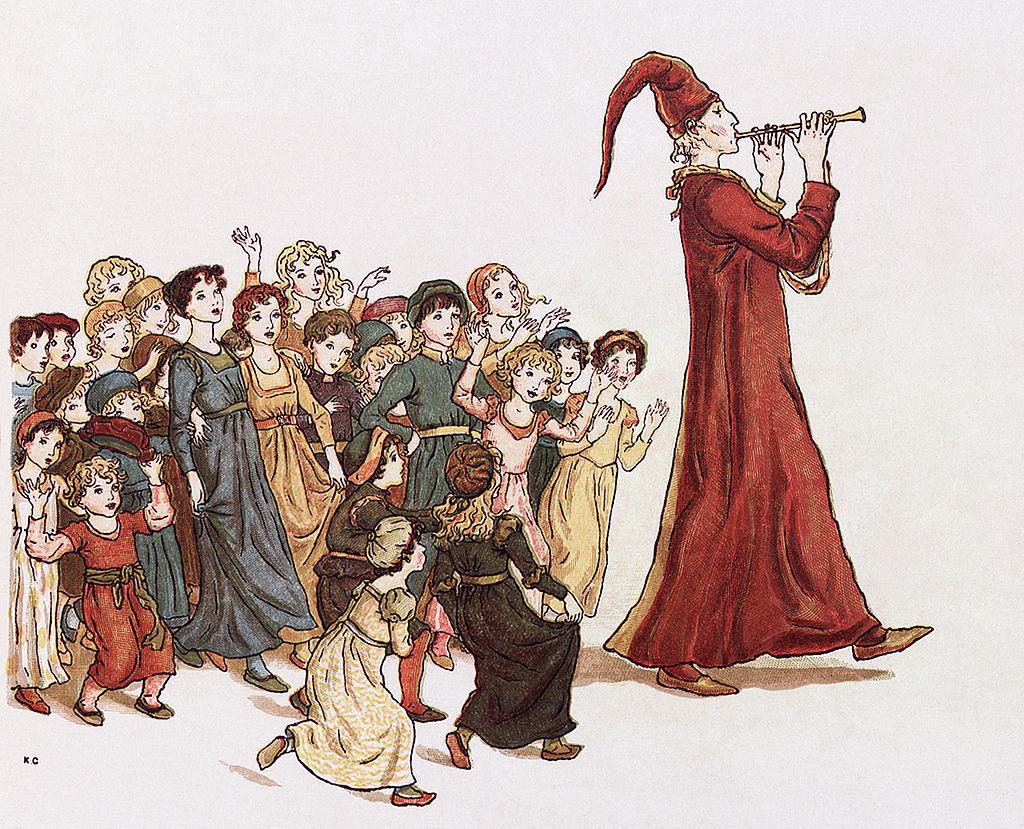

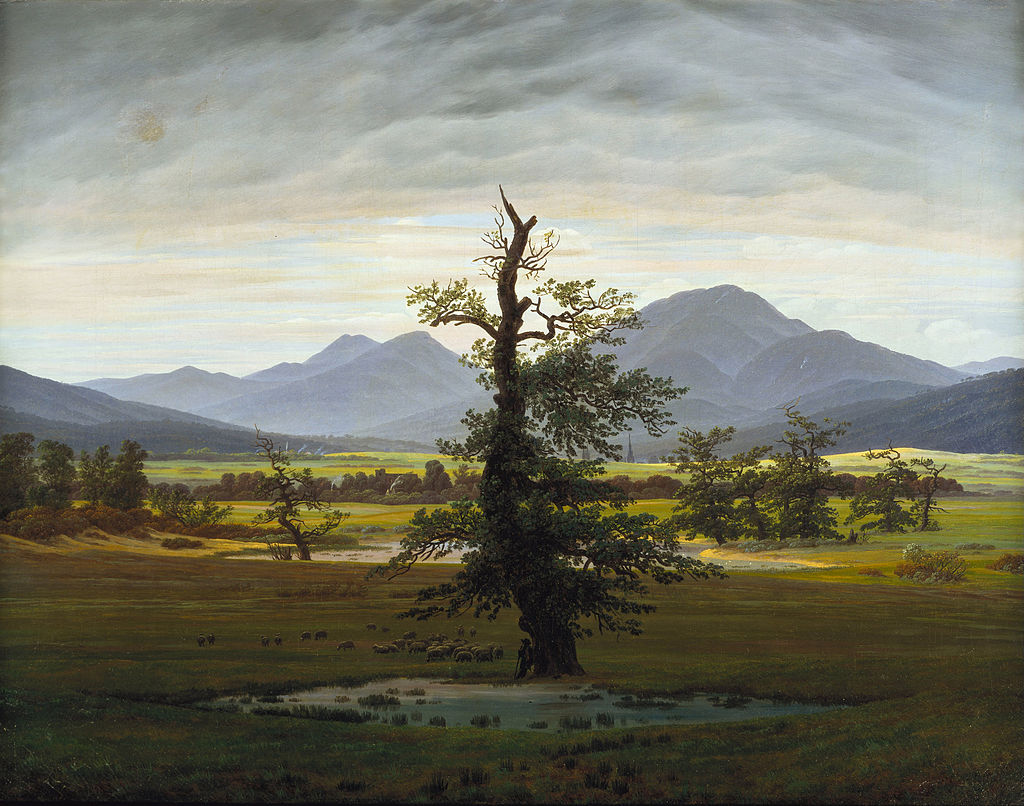

In 1822 Casper David Friedrich painted a solitary tree – a simple landscape that has become one of Germany’s most famous national paintings. The tree signifies so much – roots, stability, but also hardship, survival, that Roman defeat. It’s both heroic and lonely. It’s even used as a symbol on coins.

The German romantics later idealised folk poetry and bucolic stories in which the landscape took a central role. The feeling of nature symbolised something reason could not capture – the contradictions and mysteries and traditions that seem to arise out of it, seemingly from everywhere and nowhere, developed not from rational consciousness but given by mother earth herself.

The German barbarians had famously defeated Rome from the cover of forest – the first victory of resistance in the German cultural memory and a national identity-forming event.

The Brothers Grimm didn’t write their fairy tales – Rapunzel, Hansel & Gretel, Little Red Riding Hood, and Snow White among them. They went out like anthropologists, collecting them from locals. Jacob Grimm wrote, ‘nothing remains more perverse than the presumption inherent in writing or fabricating epic poetry [in the sense of folk poetry], since it can only write itself’.

The Grimms also spent their lives creating the first German dictionary.

It’s in this context of language, folk tales, and landscape that Germany began fermenting its own genre, its own distinctive type of critique, culture and philosophy.

And it’s for this reason of immediacy, of experience, of feeling and seeing and being immersed in place that I want to come to Germany too. Because the central thinkers of this period in the late eighteenth century also felt this. They wanted adventure, escape, growth and experience. While also emphasising the domestic – the people and language – they acknowledged the contradiction of life, being far and near simultaneously.

Goethe longed for the Mediterranean. He wrote, in some of the most famous lines in German poetry:

‘Do you know the land where the lemon-trees grow,

in darkened leaves the gold-oranges glow,

a soft wind blows from the pure blue sky,

the myrtle stands mute, and the bay-tree high?

Do you know it well?

It-s there I-d be gone’

In 1769 a young writer set off on a voyage with an unknown destination. Johann Gottfried von Herder wrote, ‘I go forth into the world as untroubled as an apostle or a philosopher, in order to see it’. He anticipated Nietzsche when he wrote, ‘to the ships, you philosophers!’

We wanted to leave behind the static texts of his study and live. Goethe was so enamoured when he met Herder that he wrote, ‘Alas! I’m still confined to prison .. ./Restricted by this great mass of books .. ./You must escape from this confining world!’

He took images and journeys and language instead of abstract ideas. He said, ‘what a wide scope for thought a ship, suspended between sky and sea, provides! Everything here adds wings to one’s thoughts, gives them motion and an ample sphere! The fluttering sail, the ever-rolling ship, the rippling waves, the flying clouds, the broad, infinite atmosphere! On land one is chained to a fixed point and restricted to the narrow limits of a situation…’.

Herder wanted to experience what he called ‘living’ reason, instead of abstract ideas, text in books, formulas and systems and deductions. He wanted to go out and understand peoples and cultures – for this reason, he anticipated modern anthropology.

He set off to explore ‘the culture of the earth-of all regions, times and peoples! forces! mingling! forms! Asiatic religion and chronology and polity and philosophy! … Greek everything! Roman everything! Northern religion, law, customs, warfare, honor! The popish age-monks, erudition … The politics of China and Japan! The natural science of a new world! American customs, etc …. A universal history of world culture!’

He wanted to collect folk songs and record culture in what he called testimonia. He said, ‘I have been stalking the way nations think, and what I’ve come up with, in a nutshell, is this: that each nation develops its own foundational documents according to the religion of its land, the traditions of its ancestors, and its concepts of Nation; and that these documents appear in poetic language, with poetic ornamentation and rhythm, as a national heritage of mythic songs on the origin of the nation’s oldest and most noteworthy features’.

He wrote what he called ‘Another Philosophy of History’, which examined how different cultures saw themselves from their own particular point of view. In this way he anticipated thinkers like Hegel, Nietzsche, and Foucault and his focus on national identity made him one of – if not the first – theorist of nationalism. Herder set off a difficult thread in history.

The Enlightenment was a period of creation, self-creation, nation-creation, the creation of new models of behaviour – machines, sciences, theories – of constructing rational replacements for traditional ways of doing things that many were seeing as defunct.

Privileges replaced with politics. Superstition replaced with scientific study. Religion replaced with ethics. An age of revolutions.

The philosophical question of importance was how these new ideas – new systems – were formed. Kant’s response was that we order the world with our reason.

But one of Kant’s disciplines – Johann Gottlieb Fichte – took Kant’s ideas and emphasised the individual doing the building work. These trends started a movement that emphasised the I replacing those traditional systems as one of irrepressible activity, full of personal energy, forming the world not in god’s image, but in their own.

Goethe wrote famously, ‘I turn back into myself and find a world’ – that within us are forces more powerful, more mysterious, more voluminous than anything we find outside of us.

Philosopher Rudiger Safranski writes that, ‘Fichte wanted to spread among his listeners the desire to be an I. Not a complacent, sentimental, passive I, however, but one that was dynamic, world-grounding, world-creating’.

All of this emphasis on immediacy, the I, the landscape, and language, built up to a thunderous movement in the 1790s. It lasted just a decade or two, but is the birth of what we call Romanticism.

In all of this we see something so often misunderstood, its significance understated, the effects of which define us today. This is the invention of the modern self and an I at the centre of a complex experience of the world, an I that feels like it’s self-determining, free, desirous – torn, in the modern world, between nature and city, between work and pleasure, between rootedness and wonder lust; what the Romantics called the finite – the everyday – and the infinite – the imagination, the spiritual, the universal, the glorious, the eternal – that something that feels bigger than ourselves.

The romantic theologian Fredrich Schleiermacher wrote that, ‘imagination is the highest and most original element in us… it is your imagination that creates the world for you’.

Schleiermacher believed that our imagination could imagine the infinite in everything – the what if? The why can’t I? The what happens if? It’s the superhuman – the thing that taught us to fly, to build castles that rise into the sky, the magic that preserves life itself. It’s the wonderous story – the creation of new fantastical fictional worlds, the imagining of political utopias. The imagination is infinite, and absolute.

The German poet and philosopher Fredrich Schlegel believed this too, feeling that we could pursue the absolute – whether that be absolute truth, absolute happiness, absolute security – but that because we are fallible creatures, because we have no certainties, no real foundations, because we are also contradictory tragic creatures, we could never quite reach it.

The human story wasn’t just about science, logic, reason, industry – but had to be more holistic. Philosophies had to contain both these things and the imagination, sentiments, national greatness with everyday life – a total story.

Novalis wrote that ‘by endowing the commonplace with a higher meaning, the ordinary with a mysterious respect, the known with the dignity of the unknown, the finite with the appearance of the infinite, I am making it Romantic’.

The Romantic movement developed through the early nineteenth century. It was the first to make some of the now common criticisms of modern life – alienation, treating the world like a machine, disregarding the emotions. It focused on the I at the centre of life, popularising new ways of telling stories about our lives, giving support to the idea that each person mattered, a precondition, maybe, for the slow democratic reforms in Europe that followed.

But many have criticised Romanticism for leading to Nazism, with its focus on national identity, blood and soil, and legitimising emotion – anger, pride, passion.

But, the Grimms and Goethe might respond: turning into yourself and finding a world doesn’t mean accepting all of that world. The romantics grappled with the contradictions of life, instead of attempting to flatten them out into a one-dimensional experience that reduces everything to logical calculation.

So, all of this set in motion a kind of a-rational (not anti-rational) philosophy that led to Hegel, Nietzsche, Heidegger and many more. It’s informed so much of how we see the world; it gave us Beethoven and the emotional orchestral music we’re used to in films; it gave us Wordsworth and his ordinary ballads; and a simple democratic focus on everyday lives that we see in so many novels, films, and soaps today. We have to remember that history – and how we see ourselves – seems inevitable to us from where we sit. But it could have always gone another way.

0 responses to “Why German History is Different”

levofloxacin where to buy – order levofloxacin 500mg pills zantac cheap