Humans love to fix things, to find the cause of a problem, to probe, tinker, and mend. We ask, in many different ways, why does this happen? What’s the root cause? What’s the origin? What or who is at fault? What or who is responsible?

But there are three subjects that have intertwined with the topic of responsibly more than others.

The idea of responsibility has many forms both historically and culturally. Philosophers have debated whether we can be truly responsible for our actions in the context of discussions about free-will; theologians have wrestled with the idea of taking responsibility for our sins; scientists have joined the discussion by searching for causation and exploring the psychology and neurology of our brains.

But today, the idea of individual responsibility is often invoked in discussions about welfare, poverty, and enterprise. Increasingly, throughout the liberal and neoliberal periods, we’ve – in politics and the media, at least – emphasised ‘responsibility for ourselves’ at the expense of other types of responsibilities, moral obligations, or duties.

For example, in his best-selling 2012 book Stepping Up, John Izzo promises his readers that “taking responsibility changes everything”.

Personal productivity author Laura M. Stack insists that “the fundamental responsibility that each of us has is that we are completely, 100% responsible for how our lives turn out”.

Jordan Peterson has written that “we must each adopt as much responsibility as possible for individual life, society, and the world”.

The focus is on responsibility for oneself – atomised, isolated, entrepreneurial – rather than on obligations to others or duties to our communities.

Philosopher Yascha Mounk has suggested that we live in an “age of responsibility”.

The idea that we should each make something of ourselves, stand up on our own two feet, take control of our lives, adopt maximum responsibility, all sound, on the surface, powerful and innocuous. They appear to be good lessons.

But as we’ll see, the rise in emphasis on this type of responsibility has weakened social bonds, justified the dismantling of welfare programmes, and encourages inwardness and blame.

And it’s almost always associated with one central topic: poverty.

If someone is to blame for their own behaviour, their own actions, and their own condition, then only they can be responsible for their poverty. Interventions are useless.

If we look to history, we’ll see that this particular interpretation of individual responsibility is relatively new, has serious flaws, and ignores more nuanced interpretations of responsibility.

Of course, the idea of individual responsibility has always existed, it’s just taken different forms and has been interpreted in many ways. And the nuance – in how the concept is composed – has important consequences.

Is poverty a personal inadequacy? A problem of persons? A problem of character? A problem of culture? Or is it a problem of place? Of systems? Of society?

First, let’s look at how the idea of the deserving and the underserving poor arose out of older ideas about responsibility. Let’s take a look at how the concept of responsibility has taken many different forms.

For most of history, poverty was a fact of life for almost everyone. Death, disease, and disadvantage were the norm, and most were at the mercy of nature, droughts, storms, dark winters, or bitter frosts. Blame and responsibility for the ‘natural condition of man’ took very different forms than they do today.

It was often not a question of who was responsible for their own poverty, but who was responsible for care. The term obligations was often used. In the 13th century, the moral philosopher and theologian Thomas Aquinas wrote extensively about the Christian’s obligation to provide support for the poor.

In England, when the Poor Laws were established after the decline of monasteries, parishes and local officials were obligated and duty bound by the crown to provide poor relief. Feudal landlords, whether they complied or not, were expected – morally and politically – to provide protection and sustenance for tenants in times of need.

An Act of Parliament in 1536 insisted that local authorities “exhort, move, stir, and provoke people to be liberal and bountifully to extend their good and charitable alms and contributions, as the poor, impotent, lame, feeble, sick and diseased people, being not able to work, may be provided, [helped], and relieved so that in no wise they nor one of them be suffered to go openly in begging . . . .”

Families also became legally responsible for each other after 1601: “[T]he father and grandfather, and the mother and grandmother, and the children of every poor, old, blind, lame and impotent person, or other poor person not able to work, being of sufficient ability, shall, at their own charge, relieve and maintain every such poor person . . . .”

In the Italian city-states of the 14th and 15th centuries, as capitalism began to emerge, a cultural ideal prevailed that it was the religious and secular authorities that that were responsible for the public good, the security and sustenance of the city’s inhabitants.

And in China, the Confucian tradition stressed obligations and relationships rather than responsibility for the self.

As capitalism released people from their dependency on the land and weakened feudalism across Europe, labour markets became more fluid, jobs came and went, and the grinding but somewhat predictable work of agricultural tillage was replaced by an unstable rise in modern industry. Modern capitalism, for all its dynamism, created a new class: the unemployed.

Take one city: Philadelphia.

In 1709 there were only 3 men and 9 women who required assistance. They were provided for by the local officials and the expenses were met through a poor tax.

It took the creation of wealth for poverty to become unpredictable and more widespread. It’s not surprising, then, that as it became more widespread, poverty increasingly became a moral condition.

In the 19th century being labelled a pauper – someone in receipt of poor relief – became stigmatised, a sign of moral failure.

The president of Harvard Josiah Quincy wrote in 1821 that there are two classes: “the impotent poor; in which denomination are included all, who are wholly incapable of work, through old age, infancy, sickness or corporeal debility”. Second were the “able poor . . . all, who are capable of work, of some nature, or other; but differing in the degree of their capacity, and in the kind of work, of which they are capable”.

At the same time a committee in Philadelphia declared that “The poor in consequence of vice, constitute here and everywhere, by far the greatest part of the poor . . . . From three-fourths to nine-tenth of the paupers in all parts of our country, may attribute their degradation to the vice of intemperance”.

Reverend Charles Burroughs preached that “in speaking of poverty, let us never forget that there is a distinction between this and pauperism. The former is an unavoidable evil, to which many are brought through necessity, and in the wise and gracious providence of God. Pauperism is the consequence of wilful error, of shameful indolence, of vicious habits. It is a misery of human creation, the pernicious work of man, the lamentable consequence of bad principles and morals”.

Biology, too, was becoming a very modern problem, the “inherited organic imperfection,—vitiated constitution or poor stock”, as the Massachusetts Board of State Charities put it in 1866.

Throughout the 19th century, the growth of interest in eugenics linked biology, heredity, and destitution as a problem that was unresolvable for those incapable of contributing adequately to the common good.

Charles Davenport – a leading US eugenicist – wanted to “purify our body politics of the feeble-minded, and the criminalistic and the wayward by using the knowledge of heredity”.

Davenport thought that immigration of what he considered lesser races would rapidly make the American population “darker in pigmentation, smaller in stature, more mercurial. . . more given to crime larceny, kidnapping, assault, murder, rape, and sex-immorality”.

The idea of ‘feeblemindedness’ took hold. Immigrants at Ellis Island were given a simple puzzle to solve and if they failed were sent back across the Atlantic. When the IQ test was invented at the beginning of the 20th century, it was administered to 2 million in the US army and a national crisis ensued when 40% of recruits were declared “feeble minded”.

The idea of national degeneration was a topic of concern across Europe and America.

Indiana passed the first state sterilization laws in 1907. 24 states followed, permitting the sterilization of the “mentally unfit”.

According the American Eugenics Society, Hitler’s sterilizations laws “showed great leadership and encourage”.

The focus on biology in the 19th century – a ‘lack of vital force’, as some put it, or ‘an inherited tendency to vice’, according to others – encouraged the idea that poverty and feeble-mindedness were an inevitable part of many individuals’ make-up, that it was unavoidable, that they were not only responsible for their condition, but there was nothing they or anyone else could do to help them.

But poverty was of course everywhere. Decent paid work hard to come by. Harvest failures, famine, disability, and illness continued to be widespread. The nineteenth century was a period of great change, low wages, and unstable markets.

And modernisation happens at varying speeds. While some areas – elite, white, and part of the metropole – got richer other areas lagged behind.

This observation called for a new understanding of poverty. It could no longer be simply a matter of singular lazy individuals. Entire groups were being left behind. A sociology of poverty was needed.

In the 1860s, the idea of a ‘criminal class’ emerged in Britain. Organised, professional and lurking the streets of cities, the idea of a distinct group became popular in the press.

These delinquents had no understanding of Christian morality, duty, or virtue, were irredeemable, and could be responded to only with a growth in the numbers and power of an organised modern police force. This was despite the fact that the majority of crime was linked to hunger, poverty, and unemployment.

A 1904 a Scotland Yard report concluded that, “the so-called unemployed have the appearance of habitual loafers rather than unemployed workmen. The poor and distressed appearance of numbers of persons met in the East End is due more to thriftlessness and intemperate habits than to absolute poverty. Poverty is brought about by a want of thrift”.

The psychiatrist Henry Maudsley argued that teaching self-control to these criminals was as foolish as “to preach moderation to the east wind, or gentleness to the hurricane”.

Criminality, according to a Royal Report, was the result of those that roamed the country in search of hand outs: “the prevalent cause [of vagrancy] was the impatience of steady labour”.

The Times in London described the criminal class as “more alien from the rest of the community than a hostile army, for they have no idea of joining the ranks of industrious labour either here or elsewhere. The civilized world is simply the carcass on which they prey, and London above all, is to them a place to sack”.

This backward and lazy group required explanation. And in the 20th century, the idea of inherent vice in distinct groups gave rise to a new area of study: the culture of poverty.

As the Cold War began, theories of development became important in the West as the communist and capitalist systems competed to improve their societies.

Hesitant to criticise structural factors, many academics in the West blamed what was termed backwardness on a ‘culture of poverty’.

These theorists took one of two routes: that culture was a problem of people – that the cause for their poverty came from inside – or that culture was a response to outside, structural causes that they often had little to no control over.

In the mid-fifties the American political scientist Edward Banfield travelled to a Southern Italian village of ‘Montegrano’ – a pseudonym for Chairomonte – to try to understand how poverty was perpetuated in the village. He saw what he described as a cultural pattern or “amoral familism”.

The villages, he argued, lived by the rules “maximize the material, short-run advantage of the nuclear family; assume that all others will do like-wise”.

In his influential book – The Moral Basis of a Backward Society – Banfield argued that the Italian villagers were inward looking, indifferent to improving their infrastructure and hesitant to provide aid to their neighbours. He described the cultural atmosphere in the village as “heavy with melancholy”.

Banfield became an advisor to three presidents, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Ronald Reagan, and argued throughout his career that the American lower classes had a similar cultural attitude to the Italian villages, sharing “distinct patterning of attitudes, values, and modes of behavior”.

But the American underclass was even worse, attaching “no value to work, sacrifice, self-improvement, or the service to family, friends, or community”.

He argued that any attempt to improve their condition through social security programmes was doomed to fail.

He wrote that “The lower-class person lives from moment to moment, he is either unable or unwilling to take account of the future or to control his impulses. Improvidence and irresponsibility are direct consequences of this failure to take the future into account . . . and these consequences have further consequences: being improvident and irresponsible, he is likely also to be unskilled, to move frequently from one dead-end job to another, to be a poor husband and father”.

Around the same time, anthropologist Oscar Lewis argued that the culture of poverty was a way of life that was passed down through generations.

He wrote that poverty “is a culture, an institution, a way of life… The family structure of the poor… is different from that of the rest of the society… There is a language of the poor, a psychology of the poor, a world view of the poor”.

There was, he continued “a high incidence of maternal deprivation, of orality, of weak ego structure, confusion of sexual identification, a lack of impulse control, a strong present-time orientation with relatively little ability to defer gratification and to plan for the future, a sense of resignation and fatalism, a widespread belief in male superiority, and a high tolerance for psychological pathology of all sorts”.

Banfield and Lewis typified research that emphasised individual fault and character deficiency over structural factors like unemployment.

But two other authors in the post-war period took a more nuanced approach. In 1965 Daniel Patrick Moynihan published The Negro Family, one of the most controversial reports on poverty in American history.

Moynihan, a sociologist and politician working under presidents Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, argued that the “subculture” of black Americans was stuck in a “tangle of pathology” and their progress in society was blocked by two main factors: the “racist virus in the American bloodstream that still afflicts us” and the “toll of three centuries of sometimes unimaginable mistreatment”.

But the problem was a cultural one and a lack of family structure, and the goal of federal intervention should be “the establishment of a stable Negro family” that was integral to “shaping the character and ability” of children. Absent fathers and matriarchal families had disastrous effects on child raising.

The report was instantly controversial, setting the terms for a debate that’s on-going today. It attracted criticisms from many liberals, including feminists, and was accused of ‘blaming the victim’.

Contradictory in places, liberals used the report to justify intervention – the subtitle, after all, was “a case for national intervention” – while conservatives used the report to argue that only racial self-help could bring black Americans out of poverty.

Sociologist Richard Cloward published Delinquency and Opportunity in 1960. Through a study of gangs, he described a new youth subculture – one that many commentators were afraid of – that was the result of the structural conditions afflicting many young Americans.

Modern American aspiration, Cloward argued, was impossible for a huge number across the country. The impossibility of the American Dream reduced the legitimacy of American values in the eyes of many and lead to a frustrated youth rebelling and searching for “non-conformist alternatives”.

But since the Great Depression and the New Deal, conservatives were on the back foot. Even Republican presidents Eisenhower and Nixon couldn’t ignore the structural factors that led to poverty and supported – as the country did – social security programmes.

After the Great Depression, and while coming to terms with the allure of communism, in both Europe and America it was impossible not to argue that unemployment, market cycles, and misfortune had a major effect on an individual’s life in ways that were beyond their own control.

While the idea of a culture of poverty was becoming popular in some circles, in political life, structural constraints and social programmes dominated the conversation.

Kennedy talked about obligations.

After his election in 1960, Kennedy was determined to attack the poverty problem in America, and after his assassination in 1963, his successor Lyndon B. Johnson adopted Kennedy’s policies and announced an “unconditional war on poverty” in 1964.

Johnson told congress that “our joint Federal-local effort must pursue poverty, pursue it wherever it exists—in city slums and small towns, in sharecropper shacks or in migrant worker camps, on Indian Reservations, among whites as well as Negroes, among the young as well as the aged, in the boom towns and in the depressed areas. Our aim is not only to relieve the symptom of poverty, but to cure it and, above all, to prevent it”.

Lyndon B. Johnson’s war on poverty focused on community initiatives. Operation Head Start, for example, created thousands of jobs in community support roles with training. In the first summer alone 100,000 were employed.

Community action was to be key.

Joseph Califano wrote that “the war on poverty was founded on the most conservative principle: Put the power in the local community, not in Washington; give people at the grassroots the ability to stand tall on their own two feet”.

In 1968 CBS produced a powerful documentary on hunger in America which inspired senate hearings and sparked widespread public interest. The power of the television put the plight of millions in front of the eyes of the comfortable in new ways.

Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty – the launch of Medicare and Medicaid, an increase in social security, and the development of welfare states in Europe coincided with the largest decline in poverty rates in history.

But beneath the surface a revolt was developing. Critics accused Democrats of being communists, anti-american. While the political debates were diverse, one topic began to emerge that was well-suited as a supplement to the idea of an intractable culture of poverty: genetics.

Educational policies had, according to conservative commentators, hit a wall. In the Harvard Educational Review in 1969, Psychologist Arthur Jenson asked, “Why has there been such uniform failure of compensatory education programs wherever they have been tried?”.

The answer? Biology.

Some children simply lacked the innate intelligence and no amount of intervention and political policy could address what was genetically inevitable.

Psychologist Richard Herrnstein wrote in The Atlantic that “the tendency to be unemployed may run in the genes of a family about as certainly as bad teeth do now”.

Lyndon B. Johnson’s economic advisors, the Council of Economic Advisors, pushed back: “the idea that the bulk of the poor are condemned to that condition because of innate deficiencies of character or intelligence has not withstood intensive analysis”.

But by the end of the sixties the stage was set. On the one hand, individuals, their genetics and their culture could be blamed for their condition. While on the other, structural conditions had to be addressed, and could be addressed by those in power.

Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty cost the taxpayer no extra money, and instead relied on pre-existing federal funds. But by the early 70s spending began to rise. The discontent of the 70s – the Oil Shocks, the Vietnam War, union disputes, and economic stagflation gave ammunition to critics of big government and social security.

As historian Michael Katz has written “Great Society poverty research proved to be the last hurrah of twentieth-century liberalism. It rested on an expectation with roots in the Progressive era that reason, science, and expertise could inform public policy and persuade a benevolent state to engineer social progress”.

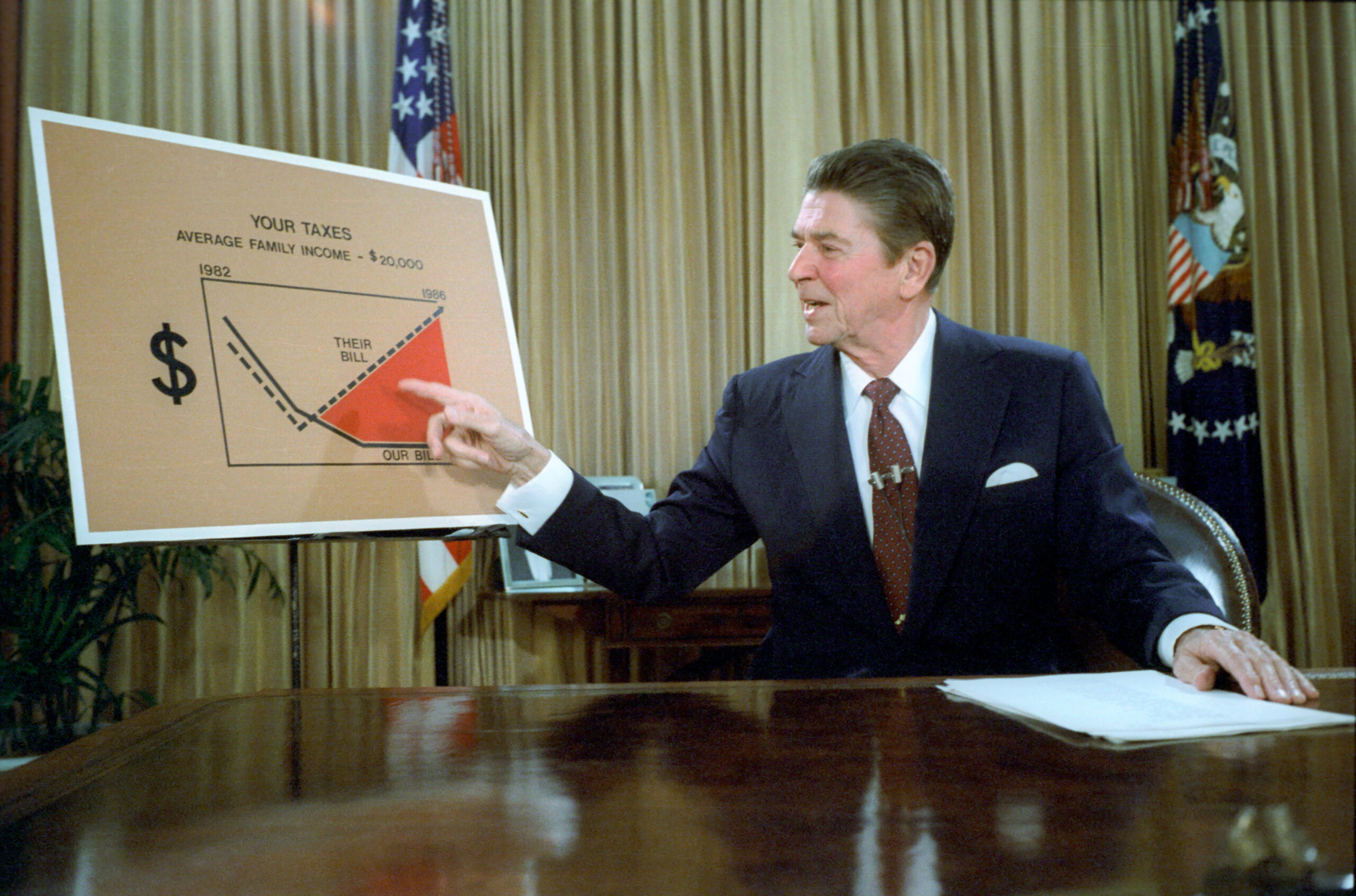

Critics of big government – like the governor of California, Ronald Reagan – wanted to “send the bums back to work”. The 1970s were the decade of a conservative backlash.

But the idea that the poor were held back by a culture of poverty also came under attack in the 70s. And instead, the idea of an ‘underclass’ emerged, still with a distinct culture but constrained by structural problems too.

In the eyes of the left, the structural problems included racism and economics, but some commentators also pointed to poverty being a problem of place. In 1977 Time Magazine reported on a underclass nurtured by a “bleak environment” producing “highly disproportionate number of the nation’s juvenile delinquents, school dropouts, drug addicts, and welfare mothers, and much of the adult crime, family disruption, urban decay, and demand for social expenditures”.

In his book The Black Underclass, Douglas Glasgow wrote that “structural factors found in market dynamics and institutional practices, as well as the legacy of racism, produce and then reinforce the cycle of poverty and, in turn, work as a pressure exerting a downward pull toward underclass status”.

But conservative critiques pointed to a structural constraint too: welfare itself. Handouts, they argued, undermined the rational incentives to work in a productive well-balanced economy.

Reagan famously declared that America had fought a war on poverty and poverty had won. Government intervention had failed. But the rhetorical shift in the 80s didn’t just place the individual at odds with the government, but atomised that individual from the rest of society, too.

Margaret Thatcher famously declared there is no such thing as society, while Reagan claimed that “We must reject the idea that every [time] a law’s broken, society is guilty rather than the lawbreaker. It is time to restore the American precept that each individual is accountable for his actions”.

More than this, it wasn’t just that individuals were responsible for their own lives, but that government was responsible for holding them back. Welfare, laziness, and moral decay were all contributing to economic stagnation, making everyone worse off.

Reagan had two bibles: George Gilder’s Wealth & Poverty, and Charles Murray’s Losing Ground.

The bestselling Wealth & Poverty was published in 1981.

It was a reimagination of capitalism, not, as Adam Smith had interpreted it, as the pursuit of self-interest, but instead as an altruistic endeavour.

“Capitalism begins with giving”, Gilder argued. “Not from greed, avarice, or even self-love can one expect the rewards of commerce but from a spirit closely akin to altruism, a regard for the needs of others, a benevolent, outgoing, and courageous temper of mind”.

The cause of poverty was an absence of “work, family, and faith”.

The burden he placed on the poor was that “in order to move up, the poor must not only work, they must worker harder than the classes above them. . . . But the current poor, white even more than black, are refusing to work hard”.

But while Gilder placed responsibility on individuals he interpreted that responsibility as one for others, not for oneself. He wrote “Capitalism transforms the gift impulse into a disciplined process of creative investment based on a continuing analysis of the needs of others”.

In Murray’s Losing Ground, however, the emphasis shifts more towards the idea that “American society is very good at reinforcing the investment of an individual in himself”.

Murray argued that poverty & delinquency had increased after 1965 despite an increase in public spending to address those problems. Black unemployment, he said, was the result of a “voluntary” withdrawal from the labour market.

Both books were instantly controversial. The central theme of both books was that government intervention had failed.

However, while it was true that poverty had gotten worse, this was because the economy as a whole had deteriorated after 1973. Studies also began to find that the number of those living under the poverty line had halved between 1965 and 1980, and welfare benefits had decreased throughout the 70s.

Historian Michael Katz writes “Murray distorted or ignored the accomplishments of social programs. He did not recognize the decline in poverty among the elderly, increased access to medical care and legal assistance, the drop in infant mortality rates, or the near abolition of hunger prior to the Reagan administration’s policies”.

By the 90s, the idea that the individual was responsible for their own life was culturally entrenched.

Clinton promised to “end welfare as we know it”, and the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act restricted welfare entitlements and emphasised individual responsibility.

In 1994, Murray’s The Bell Curve reinvigorated discussions around race, IQ, and genetics. Murray and his co-author Richard Herrnstein argued that because cognitive ability was heritable, many policies aimed at improving the condition of the worst-off were misguided.

Whatever was responsible for poverty, for the authors, was inside the head, not out in the world.

Almost every claim the book has made has been criticised or rejected. The authors misunderstood and misused statistics, and today, epigenetics – the discovery that environment can influence genetics themselves – has meant the book is almost entirely obsolete.

In Inequality by Design, several authors criticized Murray and Herrnstein, writing that “social environment during childhood matters more as a risk factor for poverty than Herrnstein and Murray report and that it matters statistically at least as much as do the test scores that purportedly measure intelligence”.

Despite this The Bell Curve sold – and continues to sell – hundreds of thousands of copies.

Much of its rhetoric emphasizes stricter welfare, genetic limitation, an inward culture of poverty, and fatherless homes. Murray wrote that “the moral hazards of government programs are clear. Unemployment compensation promotes unemployment. Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) made more families dependent and fatherless”.

Sara McLanahan and Christine Percheski point out that a substantial body of research demonstrates that living apart from one parent is associated with a “host of negative outcomes” as children score lower on tests, report lower grades, drop out of school, display a higher prevalence of behavioural and psychological problems, and are more likely to live in poverty as adults.

Through his presidency, Barack Obama frequently referred to a crisis of responsible fatherhood and healthy family.

He said to one parish “If we are honest with ourselves, we’ll admit that . . . too many fathers are also missing—missing from too many lives and too many homes. They have abandoned their responsibilities, acting like boys instead of men. And the foundations of our families are weaker because of it”.

By the 90s, these types of studies and comments were used and referred to in the context of genetic claims like Murray’s, cultural criticisms, a claimed lack of personal responsibility, and the dismantling of welfare, rather than in a conversation about structural, economic, social, or political issues.

The shape of responsibility – how its imagined, interpreted, and implement – has a complicated history. One that escapes any simple interpretation. But it seems clear that a trend has accompanied the modern history of liberalism and neoliberalism – the invention of a particular type of individual responsibility.

When Kennedy encouraged Americans to “ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country”, he seemed not to be talking about the atomised individual, responsible for themselves, but an individual with obligations to their country and to society.

Mounk has called this “the shift from a notion of responsibility-as-duty to a notion of responsibility-as-accountability”.

Philosophically, individual responsibility of this type is an often incomprehensible and contradictory concept. The original meaning of the phrase pick yourself up by the bootstraps was meant as an absurd joke, it being impossible to use your own bootstraps to pick yourself up. And this irony tells us a lot about the incomprehensibility of the concept.

Almost all the factors that contribute towards the condition of poverty come from outside the individual – education, upbringing, culture, environment, economic and unemployment. Even genetics are something an individual has no control over and cannot be held responsible for. Even if we grant that some are lazy, delinquent, in need of cultural reform, we have to simultaneously acknowledge that the education, encouragement, and solutions to those problems cannot come magically from within but must come from the guidance and aid of others.

It’s for this reason that mutual obligations make much more sense as a concept that individual responsibility.

In Why Americans Hate Welfare, Martin Gilens found the most important factor was the “widespread belief that most welfare recipients would rather sit home and collect benefits than work hard to support themselves”.

And this myth endures despite there being no evidence for it, and an abundance of evidence against it.

Firstly, unemployment aid, for example, is not expensive. In the UK, for example, it accounts for about 0.25% of the total government spending budget of £800 billion. Most only claim for temporary periods, and only about 1% of the population are claiming jobseeker’s allowance at any one time. Furthermore, the majority of people experience poverty at some point during their lives and most only experience short-term impoverishment.

And in their study, the OECD concluded that: “Reports have suggested that the benefits system has disincentivised work and encouraged a culture of dependency (see, for example, Centre for Social Justice, 2007). However, the OECD (2011a) has shown that falling relative values of benefits have increasingly contributed to rising poverty rates across countries”.

And the evidence shows that the War on Poverty, the Great Society, and federal intervention pulled millions out of poverty. Poverty declined to its lowest point in recorded history.

This N-gram shows the rise in occurrence of the phrases “individual responsibility” of “personal responsibility” in books since 1800, with a sharp rise since the late 90s. This one shows the parallel decline in the occurrences of the more outward looking “duty”.

What I hope it clear, is that I have not arguing that we should not be talking about our responsibilities, only that the particular form “individual responsibility” has taken – atomised, asocietal, ideally self-dependent, culturally ‘backward’, genetically limited – is a relatively new historical and political concept which is used to justify the dismantling of welfare, the rejection of altruism, and the unravelling of community.

Any cultural interpretation of responsibility is bound-up with politics, language, culture and society, and, has a history that’s not simply progressive and linear.

Jordan Peterson has written that “we must each adopt as much responsibility as possible for individual life, society and the world”. Instead, maybe we should remember that we’re all dependent on one another in some way, that the responsibility should be placed on the powerful not the powerless, that the dispossessed are more likely to succeed with some kind of external aid.

Instead of being responsible for ourselves, the concept of mutual obligations or duties includes responsibility to work hard and improve ourselves, but can also better accommodate contributing to the world, aiding others, remembering no man is an island and turning our gaze not inwards but outwards.

Sources

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2690243/

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2018/03/welfare-childhood/555119/

Michael Katz, The Underserving Poor

Yascha Mounnk, The Age of Responsibility: Luck, Choice, and the Welfare State

Gary B. Nash, “Poverty and Poor Relief in Pre-Revolutionary Philadelphia”. The William and Mary Quarterly 33, no. 1 (1976): 3-30. Accessed July 6, 2021. doi:10.2307/1921691.

B. Harris & P. Bridgen, “Charity & Mutual Aid in Europe & North America Since 1800”. Clive Emsley, Crime & Society in England: 1750-1900.

https://www.historyandpolicy.org/policy-papers/papers/englands-early-big-society-parish-welfare-under-old-poor-law

https://www.gotquestions.org/personal-responsibility.html

https://www.openbible.info/topics/personal_responsibility

https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/09/the-moynihan-report-an-annotated-edition/404632/

Morris, Michael. “From the Culture of Poverty to the Underclass: An Analysis of a Shift in Public Language.” The American Sociologist 20, no. 2.

Jordan Peterson, 12 Rules for Life

0 responses to “The Invention of Individual Responsibility”

Here, you can discover a wide selection of online slots from top providers.

Users can enjoy traditional machines as well as feature-packed games with high-quality visuals and interactive gameplay.

Whether you’re a beginner or a seasoned gamer, there’s something for everyone.

play aviator

All slot machines are available 24/7 and designed for PCs and smartphones alike.

No download is required, so you can jump into the action right away.

The interface is user-friendly, making it convenient to browse the collection.

Join the fun, and dive into the world of online slots!